A Journey Along the Santa Cruz River

Sonoran Institute

Key Concepts

- The Santa Cruz River is a critical cross-border waterway in southern Arizona which forms in Santa Cruz County’s San Rafael Valley, flows into Mexico and crosses back into the U.S. near Nogales. From there, it flows through Rio Rico and Tubac on the way to Tucson and the river’s end at the Gila River near Phoenix

- Pumping of groundwater for human use has dried many naturally flowing stretches of the Santa Cruz River.

- High-quality water is released into the river from wastewater treatment plants and is sustaining river flows, creating important wildlife habitat, and is helping raise the water table.

- Most of the water released into the river in Santa Cruz County comes from Mexico and is treated at the Nogales International Treatment Plant in Rio Rico.

Key Terms

- Headwaters – the source of a river or stream.

- Confluence – the place where two or more streams come together; often where a smaller stream or river joins a larger river or waterway.

- Tributary river – a smaller river which flows into a larger river

- Aquifer – the body of groundwater that is found in the layers of dirt, rock, and unconsolidated materials underground.

- Percolation – is the process in which liquid (like water) slowly filters downwards into the aquifer

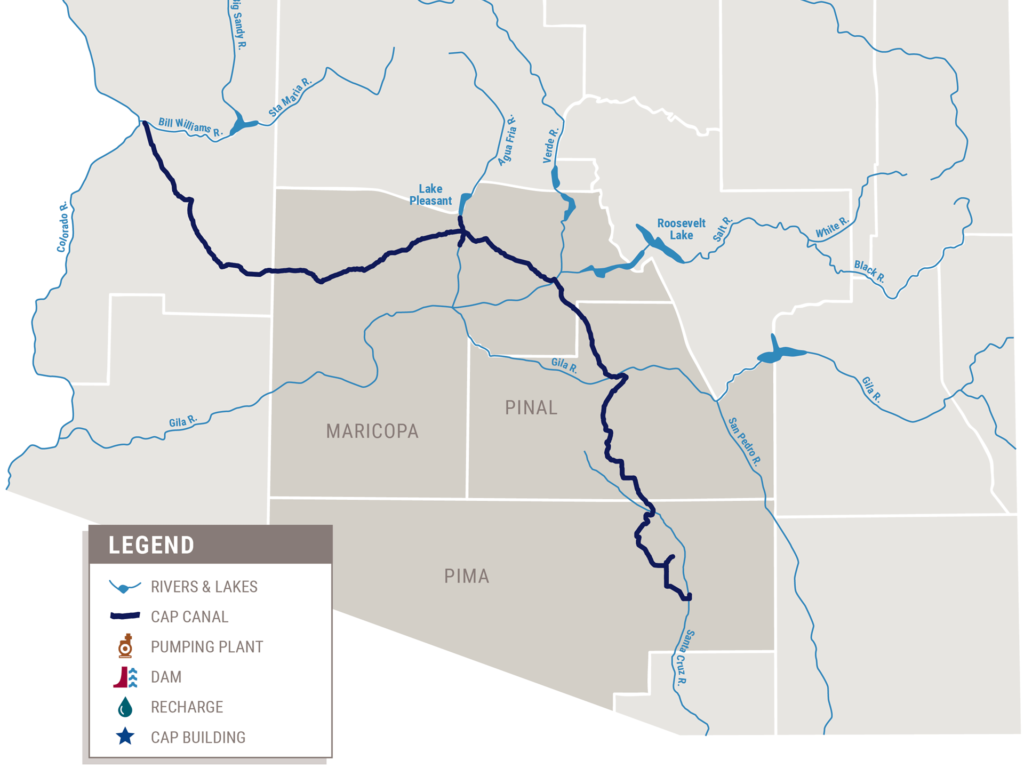

- Central Arizona Project – a 336-mile canal that pumps water from the Colorado River to cities and farms in central and southern Arizona. Learn more: https://www.cap-az.com/

- Wastewater Treatment Plant – a facility that removes and eliminates contaminants from water that goes into the sewer system from businesses and residences. The resulting cleaner water, often called effluent, recycled, or reclaimed water, is often released back into the environment (often in rivers) and is back in the water cycle.

- Naturally Occurring Flow – places along the river where the groundwater comes up to the surface and creates flowing water in the river. This is in contrast to places where the river is flowing because we’ve released clean effluent from our wastewater treatment plants.

RESEARCH ARTICLE

A2. Why is the Santa Cruz River Important?

A Journey Along the Santa Cruz River

Sonoran Institute

Water is essential for all life. Few places better remind us of this than deserts. Although most of Santa Cruz County is cooler than surrounding desert lands in Arizona and Sonora, it is still very dry and surface water is scarce. It is because of this that the Santa Cruz River which begins in the county’s eastern hills south of Sonoita, is so special. Although a lot of the river is now dry most of the year because of groundwater pumping, the Santa Cruz River mostly flows underground but is fed by creeks and arroyos running down from mountains in every direction. This river, which flows from our county into Mexico before turning around and reentering Arizona east of Nogales, is a vital American and Mexican river in the dry Sonoran Desert of Southern Arizona as it flows northwards past Tucson and ends near Phoenix. This begins our journey along Santa Cruz County’s most valuable natural resource – the waters of the Río Santa Cruz.

A Journey Along the Santa Cruz River

Santa Cruz River in Santa Cruz County, Arizona. Photo by Bill Hatcher for the Sonoran Institute.

For many of its miles, the Santa Cruz River is a dry sandy riverbed inhabited by tough desert creatures and vegetation. From headwaters in the mountains of eastern Santa Cruz County to its confluence with the Gila River near Phoenix, the Santa Cruz River moves through mountain, grassland, and desert terrain, flowing in some stretches with used and treated water supplied by humans. The source of streams or rivers like the Rio Santa Cruz are called headwaters. The Santa Cruz River’s headwaters are mainly the Canelo Hills south of Sonoita and the Patagonia Mountains. Runoff, or water running down, from these mountains after snow or rainstorms nourish the river’s waters.

The Santa Cruz River in Kino Springs (east of Nogales) shortly after reentering the United States. The Patagonia Mountains are in the distance. Photo by Carlos F. Parra.

The river flows south into Mexico near the ghost town of Lochiel, passes the historic town of Santa Cruz, Sonora, Mexico and then makes a dramatic turn northward returning into the United States east of Nogales through Kino Springs. The Santa Cruz River flows northward through Santa Cruz County fed by tributaries (smaller streams or rivers which flow into a larger river) like the Nogales Wash and Sonoita Creek. The flow continues past Rio Rico, Tumacacori, and Tubac before crossing into Pima County, Tucson, Marana, and eventually just south of Phoenix where it has its confluence (the place where two or more streams come together) with the Gila River.

Fall along the Santa Cruz River near Tumacácori. Photo by Bill Hatcher for the Sonoran Institute.

The Santa Cruz River is tributary of the Gila River, but the Gila River is itself a tributary of a much larger river it meets all the way west in Yuma, Arizona – the Colorado River. Known as the workhorse of the West, the Colorado River, a famous natural celebrity for its monumental dams and pioneer front, is itself formed by similar processes like the much small Santa Cruz River – runoff from mountain ranges, in this case the mighty Rocky Mountains. The journeys of these two rivers are quite different, but the water in both meets the same fate.

Humans and the Santa Cruz River

Humans have lived in the Santa Cruz River valley dating back over 12,000 years. In the past, available water, lush trees, and abundant wildlife would have sustained hunter-gatherers, followed by agricultural communities, moving right up to modern times. Portions of the Santa Cruz River would flow year-round until 1910! In the 1700s, Spanish colonizers began changing and disrupting Indigenous practices of water use and agriculture, mandating Western and religious practices upon the long-established communities of Indigenous O’odham peoples in the Santa Cruz River valley. This continued into the 1900s, when American western expansion brought ranching, mining, and forestry into the valley, further disrupting the Indigenous way of life.

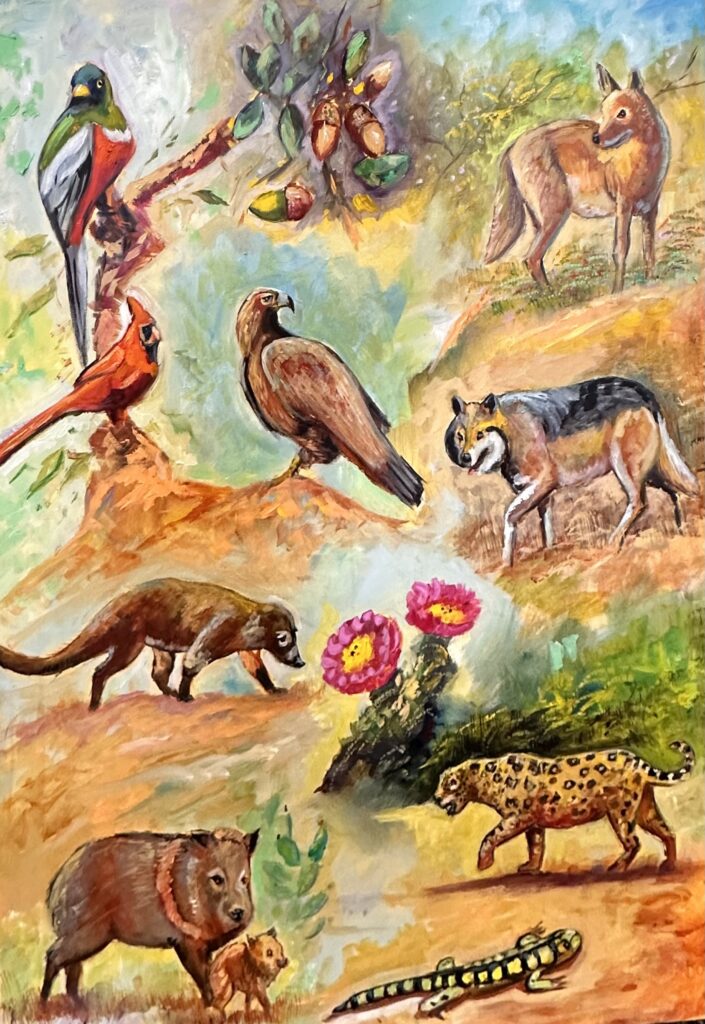

Santa Cruz County’s Magical Natural World

Armando Moreno (2024), Oil on Canvas

Key to American western expansion was a mindset that water and land were to be used to the greatest degree. Over the 1800s and into the late 1900s, the Santa Cruz River valley’s mesquite trees were chopped down for fuel to power groundwater pumps that extracted geologically ancient water from the aquifer underground for use on the surface. An aquifer is the body of groundwater that is found in the layers of dirt, rock, and unconsolidated materials underground. More people and more ranches meant more water needed to be used, and to power this cycle, more trees were felled. It was a vicious cycle. In the Tucson reach of the river, the Santa Cruz River’s perennial flows ceased by 1910, and by 1940, even the reliable seasonal flows driven by summer monsoons and winter rains ceased, except in response to storms.

After a century of overuse, the Santa Cruz River dried up, but more people moved into the valley and needed ever more water. So, more wells were drilled and groundwater extracted until, in the 1950s, scientists studying the Pima County portion of the basin realized that we were withdrawing more water from the aquifer than was percolating underground. Percolating is the process in which water slowly filters downwards into the aquifer. This process of water overuse is called overdrafting; it’s like taking more money out of your bank account than you have going into it. Those scientists forecasted that both Pima and Santa Cruz Counties had overdrawn the river and groundwater system and alarm bells started ringing.

In the early 1990s, the Central Arizona Project (CAP) started delivering water to Tucson—uphill!—from the Colorado River. CAP is a 336-mile man-made canal that pumps water uphill from the Colorado River to cities and farms in central and southern Arizona. This remains the primary source of water for Tucson and into Green Valley. In Santa Cruz County, groundwater pumped out of the local aquifer remains the primary source of drinking water where we are fortunate enough to have low population and a water conservation ethic. Good job, Santa Cruz County.

Flows in the river in Santa Cruz County are supported by water released from the Nogales International Wastewater Treatment Plant in Rio Rico. The wastewater treatment plant treats water from Ambos Nogales and Rio Rico, with over 80% of the water coming from Mexico. In 2009, the facility received a big upgrade that improved the water that it discharged into the Santa Cruz. Prior to those upgrades, the water was slimy, stinky, and dangerous. People up and down the Santa Cruz River valley avoided the river because of this.

But, by improving the water coming into the river at the Rio Rico treatment plant (and the 2 treatment plants up in Pima County), the life in the river started coming back! Endangered fish like the Gila Topminnow reappeared in the river in 2015 near Nogales and in 2017 near Tucson after having been absent for over 70 years. Dragonflies, fish, birds, wildlife…and now people, have been reconnecting with this cleaner river. It’s a beautiful thing for the Santa Cruz to come back to life!

Through Arizona’s San Rafael Valley and across the USA–Mexico international border into Sonora, Mexico, the river has a naturally occurring flow for only short and variable stretches. Along these brief reaches, the resilient Santa Cruz sparkles in the sun. Over shallow rocks, the Santa Cruz River harmonizes with birdsong and raptor cries, with the snuffles of javelina and silent padding of elusive wild cats.

Along the Nogales stretch of the river, from Rio Rico to Amado, the clean water in the Santa Cruz River is once again tumbling downstream. It glistens on wet river stones and is whirled around by the flicking tails of native fishes—the longfin dace and Gila topminnow. There are non-natives too, and anyone who has walked along the banks of the Santa Cruz, whether running or dry, knows that there is inevitably a large amount of trash as well. The Santa Cruz River moves through it all, with some difficulty at times. Past tree and bridge, under hawk and hummingbird, and beside volunteer trash surveys and cleanups hosted by Friends of the Santa Cruz River and Tumacácori National Historical Park. With any luck, the river might make it close to Amado before it disappears again underground. The flow from the Nogales International Wastewater Treatment Plant in Rio Rico has reached over 17 miles in the past, beyond Chavez Siding Rd. Although with upgrades to the treatment plant in 2009 the river rarely flows so far now because more water percolates into the streambed, recharging the aquifer below and raising the water table, or level of the water stored underground—it’s a great thing!

Through Green Valley and Sahuarita the now-dry riverbed winds, any remaining subflow deep below the surface with the far away bedrock. South of Tucson, near Martinez Hill, the bedrock rises to push subflow to the surface, but in the 1940’s the river that once flowed from here through modern-day Tucson was dried by the city’s multiplying wells. Tribal water settlements have now returned irrigation capacity to the San Xavier District of the Tohono O’odham Nation, resulting in runoff that has helped to recharge local groundwater. Water has been rediscovered near Martinez Hill, but it does not reach the city. Our flowing river’s story is picked up instead in downtown Tucson, supported by water from a distant river cousin—the Colorado River. Water from the Colorado River has made its way to the Santa Cruz after traveling along the Central Arizona Project, mixing with local groundwater, and being used by local business and residents, treated at a wastewater facility, and finally released into the Santa Cruz.

Conclusion

The Santa Cruz River is a fascinating water body with most of its water coming from Mexico and the Colorado River. Through releases like those from the Nogales treatment plant in Rio Rico, and facilities in Pima County, we are helping to support the river and create a new and brighter future for the environment around us. In a desert environment like that in Santa Cruz County it is important to value and protect the Río Santa Cruz – our most vital natural resource – from contamination and overuse.

About the Authors

Sonoran Institute, a non-profit organization, is working to make the Santa Cruz River a living, flowing river and the foundation of community health and prosperity from Mexico to Marana. Since 1990, the Sonoran Institute’s mission has been to connect people and communities with the natural resources that nourish and sustain them. www.sonoraninstitute.org

Bibliography

Logan, Michael F. The Lessening Stream, An Environmental History of the Santa Cruz River. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2002.