Arizona-Sonora Borderlands Endangered Species Conservation

Gabriella M. Vanover, University of Arizona Student

“El Jefe” roaming around our county’s Santa Rita Mountains in 2016 (Conservation CATalyst and the Centre for Biological Diversity)

Key Concepts:

- The socioecological significance of Santa Cruz County’s endangered jaguars

- Spotlight on Macho B & El Jefe, Santa Cruz County’s two famous jaguars

- Humans in Southern Arizona have had a difficult historical relationship with jaguars, as habitat loss, urban developments, and ideologies have threatened their existence

- A review of local opportunities for getting involved and supporting the conservation of endangered borderland species

Key Terms:

- Biodiversity: the variety and variability of life on Earth

- Biomass: the amount of organic plant matter in an ecosystem

- Biotic: relating to living things

- Conservation: management of natural resources as a method of preservation & protection

- Desiccated: dried up

- Ecological Corridor: areas of natural habitat that connect wildlife populations separated by human activity

- Keystone Species: a species that helps to hold the ecosystem together

- Riparian: habitat located near a water source

Research Article

A3. Why are Santa Cruz County’s Jaguars Significant?

Arizona-Sonora Borderlands Endangered Species Conservation

Gabriella M. Vanover, University of Arizona Student

Introduction

“Viva El Jefe!” reads the August 2022 headlines in Arizona – the jaguars are back! These magnificent cats, recognizable by their distinct spots, have been making the journey between the U.S. and Mexico for years, stirring up news each time one is sighted north of the border. For the past fifty years, jaguars have faced significant risks like urbanization and deforestation that have threatened their survival in the U.S. However, with the help of conservation groups and local support, endangered species like jaguars are returning to the U.S. and restoring the predator-prey balance in this community.

Santa Cruz County in Southern Arizona has long been recognized as an international gateway between Mexico and the United States. The county is famous for its diverse cultural scene as a U.S.-Mexico border community, but not many outsiders recognize its value as a major ecological gateway between the two countries. Resting between the Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts, this desert ecosystem boasts an impressively biodiverse, or varied, population in plants and animals alike. Yet like many of the world’s natural communities, this borderland wildlife territory is endangered by human activity, climate change, and dwindling natural resources. Many of these animals are endangered due to overhunting and habitat loss, most notably jaguars. Once a prominent species of the Southwest, jaguars were largely eradicated from North America during the twentieth century; for the last thirty years, jaguar sightings in the U.S. have been extremely rare.[1] The fractured relationship between humans and predatory species has driven jaguars out of the United States, but through conservation and activism, the people of Santa Cruz County have an opportunity to bring the jaguar back to Arizona (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A trail camera in the Santa Rita Mountains, set by Chris Bugbee, captures Santa Cruz County’s beloved jaguar, El Jefe, roaming the mountain range in 2016. Image courtesy of Conservation CATalyst.[2]

Historical Range of the Jaguar

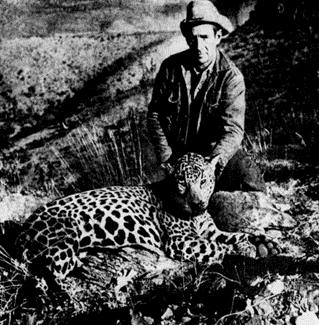

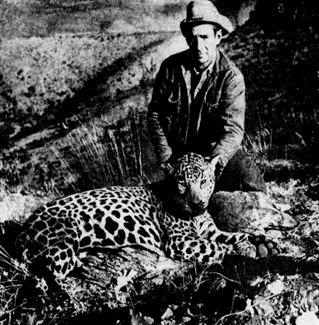

When you think of the word “jaguar,” it is likely that you imagine a large, stealthy cat, weaving its way through the underbrush of a tropical rainforest. You may even imagine a pair of fiery, golden eyes peering down at you from the vibrant green canopy. Yet, jaguars exist in numerous different habitats, including the arid landscape of Southwest Arizona. Documents show that this magnificent cat roamed “as far north as the Grand Canyon,” a significant stretch of desert terrain for an animal to cover. [3] Prior to the twentieth century, the jaguar coexisted with many Indigenous peoples of the American Southwest, who viewed the big cat as a god and immortalized its image through art. [4] Over time, differing views of the jaguar developed; while some communities saw the cat as a god, others claimed it was a mythical creature. However, by the twentieth century, However, by the twentieth century, the jaguar had become akin to a trophy, as trappers and hunters sought to add the spotted pelts to their collection (Figure 2). Unlike past civilizations, who revered the jaguar, southwest ranchers and hunters killed numerous jaguars for preying on livestock before protection was established in 1968. [5] Still, it is primarily our fractured understanding of jaguars and the roles they play within the Southwest ecosystem that has shaped our relationship with these big cats.

Figure 2. A trapper poses with a jaguar that was caught in a lion trap.[6]

Jaguars play an important role in the ecological pyramid as a predatory species. Although lived experiences often teach us to fear or dislike predators, they help to maintain biodiversity within their biotic, or living, communities. Herbivorous species can consume and reproduce freely when carnivorous species are not present; this often decreases biomass, the amount of organic plant matter in an ecosystem.[7] Without predators to maintain balance between the plants that produce energy and the consumers that eat the plants, habitats run the risk of losing endangered plant species and experiencing overcrowding of prey species. If major hunters like coyotes and ocelots vanish from the environment, species like rabbits and packrats multiply excessively and overconsume grass and native plants as a result. Jaguars are especially important to the desert ecosystem because they are opportunistic hunters, meaning they prey on nearly all species rather than a select few.[8] They can hunt at any time during the day or night and often travel lengths to find prey. Jaguars act as a keystone species in all habitats they are found in; restoring their presence in Santa Cruz County will be the first step towards healing the ecosystem that has been damaged by habitat loss and the community that has feared jaguars for decades.

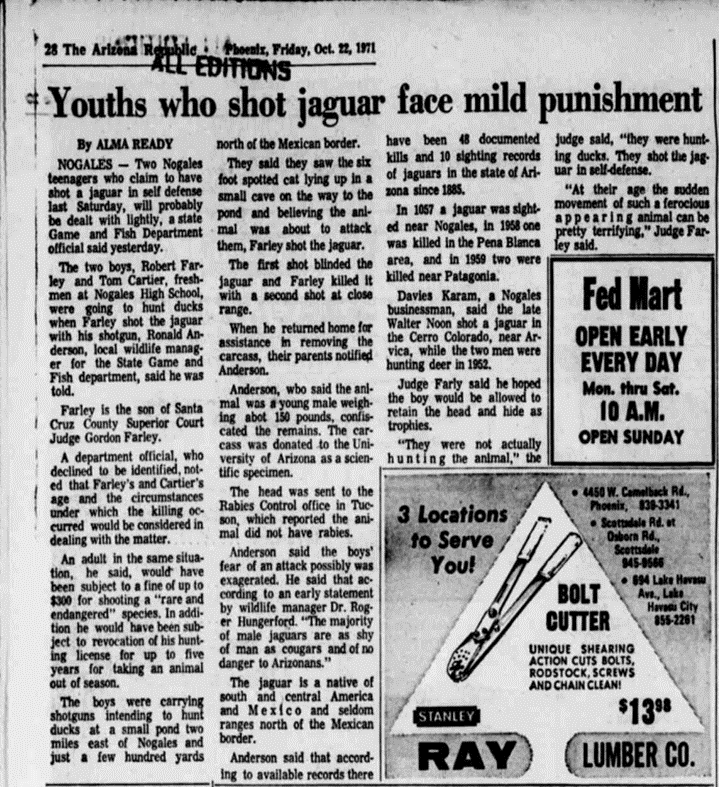

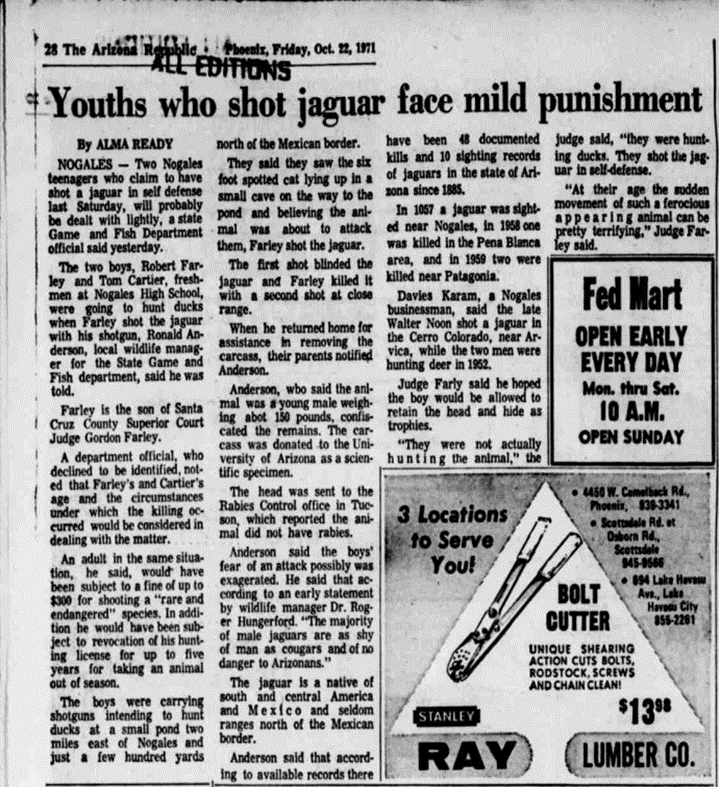

One of the most notable interactions involves the killing of a jaguar by two boys from Nogales. In 1971, Robert Farley and Tom Cartier faced charges for shooting a jaguar on the Santa Cruz River, just north of the U.S.-Mexico border near where the Little Red Schoolhouse is located.[9] Though the young men claimed they shot the cat in self-defense, Ronald Anderson, the local wildlife manager, suggests their fear was distorted. “The majority of male jaguars are as shy of man as cougars,” he claims in a statement to the newspaper, “and of no danger to Arizonans.”[10] The boys believed they were in danger because they had no previous experience with jaguars or how they typically behaved. They had experienced jaguars as a threat to livestock and their communities and felt that they would be safer by eliminating the cat completely.

Ready, Alma. “Youths Who Shot Jaguar Face Mild Punishment.” The Arizona Republic. October 22, 1971: 28.

Residents defended the boys’ actions; even Judge Farly, who oversaw their trial, said he “hoped the boy[s] would be allowed to retain the head and hide as trophies.”[11] By not acknowledging the importance of the jaguar to the desert ecosystem, Santa Cruz County helped to keep jaguars out of the U.S. for thirty years, unknowingly pushing other important predators, like coyotes and Mexican gray wolves out of the picture as well.

The increase in technology has allowed for a closer monitoring of remote areas; trail cameras strategically placed have captured multiple jaguars roaming the mountains of Arizona over the years. Personal connection to specific jaguars has increased support for the presence of jaguars in Arizona. Arizonans and Mexicans have kept a close eye on two jaguars that have become beloved figures to the borderland community: Macho B and El Jefe. Jack Childs, a rancher and hunter from Southern Arizona, first spotted Macho B in 1996 in the Baboquivari Mountains.[12] As the first jaguar to be spotted in southern Arizona since their disappearance, officials were quick to establish a system of cameras around the border.

At the time, Macho B was the last known jaguar in the U.S.; his presence helped conservation groups advocate for the maintenance of protected land, especially around the border. However, in 2009, Macho B was euthanized by Arizona Game and Fish officials after he became injured in a leg snare.[13]

Macho B’s unfortunate demise sparked a local and national investigation into whether enough was being done to protect jaguars and their habitats. Without further protective action from the federal government, “it’d be all over,” said Jon Schwedler, a conservationist for the Northern Jaguar Project; “you [can] kiss the jaguar goodbye.”[14]

After the unfortunate loss of Macho B, another jaguar, dubbed El Jefe, restored hope in the jaguar conservation moment and the potential for jaguars to return to the U.S. [15] When El Jefe was first spotted in 2011, it caught the attention of the national media. The virality of his appearance helped conservationists to delay the establishment of a new open pit mine in the Santa Rita Mountains, where El Jefe resided.[16] To this day, the mine remains a proposed project, thanks to El Jefe. Although sightings are rare, his presence in Arizona helps raise awareness about the importance of preserving ecological relationships and species’ ability to migrate between territories.

The first jaguar photographed in Arizona since its eradication from the U.S. was in 1996, the same year that Macho B was sighted (Figure 3). On a hunt for mountain lions in the Peloncillo Mountains, fourth-generation rancher Warner Glenn stumbled upon the elusive jaguar after miles of tracking the predator. He was shocked by how strong the cat was, saying, “[I] couldn’t believe any lion could run this far, this fast, and not give out… the jaguar was not panting or out of breath.”[17] His encounter was an unlikely scenario; as the U.S. Southwest becomes increasingly populated with human activity, jaguars have been forced to relocate further into Mexico, primarily residing in Sonora. Since Glenn’s encounter, jaguar sightings have increased not only in New Mexico but in Arizona as well. Macho B, the first confirmed jaguar in Arizona since their disappearance, was spotted in 1996 as well. His presence in Arizona stirred interest in bringing jaguars back to the U.S. These wild cats, which once roamed freely within Arizona’s mountains, now face border walls, humans, and a lack of resources preventing them from traveling into the U.S. Of these three stressors, the construction of the U.S.-Mexico border wall is undoubtedly the greatest offender.

Figure 3. Plate 5 from Eyes of fire: Encounter with a Borderlands Jaguar shows the jaguar leaving the cliff face in an attempt to escape Glenn and his hounds. [18]

The thirty-foot border wall, a plan implemented by the U.S. government from 2017-2021 to reduce undocumented immigrant migration into the U.S. stresses both human and wildlife interactions.[19] The physical construction of the wall has been environmentally devasting, with its victims including mountains, native plants, and water sources. Guadalupe Canyon, located in southeastern Cochise County at the Arizona-New Mexico-Sonora boundary, suffered significantly. Miles of native vegetation and rock formations were dynamited, bulldozed, and destroyed to make room for the towering steel fenceposts.[20] Despite local efforts to save this natural area, the biotic strength of the canyon has been vastly depleted (Figure 4). Guadalupe Canyon was once a flourishing ecological corridor, ushering migratory species like ocelots, jaguars, and various birds from Mexico through its riparian gateway into Arizona and New Mexico. Now, these animals are forced to look elsewhere to travel north, infringing on rangelands and threatening the safety of both parties involved. As these migratory species are forced closer to human settlements, they pose a greater risk to livestock and local agriculture, an issue that has already caused problems in the past for borderland farmers and ranchers.

With segments of the border wall running through typical ecological corridors, jaguars and other threatened species are forced to search for breaks, expending precious energy towards finding these gaps. [21] In a desert ecosystem where water is not always easily accessible, going the extra mile wastes energy that could be life or death for these creatures. Smaller animals and birds can work around the border wall but suffer from the desiccated landscape caused by construction. Land clearing and an introduction of heavy metals to water sources near the border force species to risk the journey even further north, often dooming them to death. Expansion of human settlements into natural areas has increased the tension between humans and wildlife, as many rural settlements own livestock threatened by wild predators. Terrestrial predators like jaguars and Mexican gray wolves are forced to navigate higher elevations to find isolation, making the journey even more treacherous for some.

This is especially problematic for jaguars, as no females have been found in the United States for decades. The male jaguars like El Jefe must make the dangerous journey back into Mexico to reproduce, but with completion of the border wall likely to happen, the future of these species remains unclear.

Figure 4. A rancher stands next to the unfinished border wall in Cochise County’s Guadalupe Canyon. Image courtesy of The Washington Post, by Salwan Georges. [22]

Next Steps

Santa Cruz County could serve as a wildlife corridor for these endangered species now that many areas of the Southwest are obstructed by manmade structures. Residents can start by supporting organizations dedicated to the preservation of native keystone species and habitats in the borderlands, like the Northern Jaguar Project. This organization works to preserve and protect the jaguar population and their native habitats in Arizona and Mexico. [23] Advocating for conservation organizations increases monitoring and maintenance efforts to keep these areas safe for migrating species. However, organizations are not the only factor in successful conservation efforts; Glenn’s encounter with a jaguar in 1996 showed that even ranchers, hunters, and “ordinary” people can appreciate and support biodiversity. Individuals can participate in conservation by planting native plants in their communities; these plants provide rest stops for birds and insects to refuel along their journey.

It is also crucial for young people in the area to connect with representatives who will advocate for the preservation of Santa Cruz County’s ecological diversity. Taking these steps towards conservation increases survivability of these endangered species and preserves the rich environmental history of Santa Cruz County for future generations to enjoy.

Jaguar Borderlands: Santa Cruz County

Miguel Grijalva (2024), Oil on Canvas

Author Bio

Gabriella Vanover is a senior undergraduate student at the University of Arizona pursuing a Bachelor of Arts in History with minors in Natural Resources & Education. Hailing from the Pacific Northwest, she has moved to Tucson to learn more about the environmental history of desert ecosystems. Gabriella is a curatorial and research assistant at the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, where she will continue to work after finishing her education. She has a vested interest in museum curation and educational outreach, particularly in natural and ecological histories. This is her first experience working with a community organization to produce research for the benefit of the Santa Cruz County community.

Bibliography

The Arizona Republic. “Jaguar Taken In Lion Trap.” The Arizona Republic. January 22, 1964: 35.

The Associated Press. “Endangered Jaguar Previously Unknown to U.S. Is Caught on Camera in Arizona.” CBS News, January 10, 2024. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/endangered-jaguar-spotted-in-arizona-previously-unknown-to-us/.

Blakeslee, Sandra. “Gone for Decades, Jaguars Steal Back to the Southwest.” New York Times (1923-), Oct 10, 2006, 3-4, https://ezproxy.library.arizona.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/gone-decades-jaguars-steal-back-southwest/docview/93018188/se-2 (accessed May 5, 2024).

Brocious, Ariana. “In Arizona, Building a Wall – and Destroying a Canyon.” AZPM, October 30, 2020. https://news.azpm.org/p/news-splash/2020/10/30/183147-the-borderlands-boondoggle/.

Center for Biological Diversity. “Viva El Jefe! Arizona’s Famous Jaguar Lives, but What’s His Future?” Center for Biological Diversity, September 22, 2023. https://biologicaldiversity.org/w/news/press-releases/viva-el-jefe-arizonas-infamous-jaguar-lives-but-whats-his-future-2022-08-04/.

Chambers, Samuel, et al, “Spatial Models of Jaguar Energy Expenditure in Response to Border Wall Construction and Remediation,” Frontiers in Conservation Science (Oct. 2022): 1-9

Culver, Melanie, and Ron Thompson. “Updates of Historic and Contemporary Records of Jaguars (Panthera onca) from Arizona.” Journal of the Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science, 4 March 2022, 65–91. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359007691.

Davis, Tony. “Did Jaguar Macho B Have to Die? Phoenix Zoo May Have Moved Too Fast to Euthanize Him, UA Pathologist Says.” Center for Biological Diversity, March 29, 2009. https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/news/center/articles/2009/arizona-daily-star-03-29-2009.html.

Daw, Sonya. “Western Yellow-Billed Cuckoo (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, November 2014. https://www.nps.gov/articles/western-yellow-billed-cuckoo.htm.

Glenn, Warner. Eyes of fire: Encounter with a Borderlands Jaguar. Edited by Ray Turner. El Paso: Printing Corner Press, 1996.

Grant, Richard. “The Return of the Great American Jaguar: The Story of Tracking a Legendary Feline Named El Jefe Through the Arizona Mountains.” Smithsonian Magazine, October 2016. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/return-great-american-jaguar-180960443/

Martinez del Rio, Carlos, Barb Dugelby, Brian Miller, Reed Noss, and Mike Phillips. “The Importance of Large Carnivores to Healthy Ecosystems.” Endangered Species Update, 18 (2001): 202–16.

Miroff, Nick. “Where Trump’s Border Wall Left Deep Scars and Open Gaps, Biden Plans Repair Job.” The Washington Post, February 19, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2022/02/19/trump-biden-border-wall/.

Northern Jaguar Project. “Our Mission.” NORTHERN JAGUAR PROJECT. Accessed May 3, 2024. https://www.northernjaguarproject.org/.

Pavlik, Steve. “Rohonas and Spotted Lions: The Historical and Cultural Occurrence of the Jaguar, Panthera onca, among the Native Tribes of the American Southwest.” Wicazo Sa Review 18, no. 1 (2003): 157–75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1409436.

Ready, Alma. “Youths Who Shot Jaguar Face Mild Punishment.” The Arizona Republic. October 22, 1971: 28.

World Wildlife Fund. “Here Are Our Top 10 Facts about Jaguars.” WWF. Accessed May 3, 2024. https://www.wwf.org.uk/learn/fascinating-facts/jaguars.

Primary Documents:

Document 1:

Ready, Alma. “Youths Who Shot Jaguar Face Mild Punishment.” The Arizona Republic. October 22, 1971: 28.

Document 2:

The Arizona Republic. “Jaguar Taken In Lion Trap.” The Arizona Republic. January 22, 1964: 35.

Document 3:

Plate 2 and Plate 5 from Eyes of fire: Encounter with a Borderlands Jaguar.

[1] The Associated Press. “Endangered Jaguar Previously Unknown to U.S. Is Caught on Camera in Arizona.” CBS News, January 10, 2024. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/endangered-jaguar-spotted-in-arizona-previously-unknown-to-us/.

[2] Grant, Richard. “The Return of the Great American Jaguar: The Story of Tracking a Legendary Feline Named El Jefe Through the Arizona Mountains.” Smithsonian Magazine, October 2016. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/return-great-american-jaguar-180960443/

[3] Pavlik, Steve. “Rohonas and Spotted Lions: The Historical and Cultural Occurrence of the Jaguar, Panthera onca, among the Native Tribes of the American Southwest.” Wicazo Sa Review 18, no. 1 (2003): 157–75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1409436.

[4] Pavlik, 160.

[5] Culver, Melanie, and Ron Thompson. “Updates of Historic and Contemporary Records of Jaguars (Panthera onca) from Arizona.” Journal of the Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science, 4 March 2022, 65–91. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359007691.

[6] The Arizona Republic. “Jaguar Taken In Lion Trap.” The Arizona Republic. January 22, 1964: 35.

[7] Martinez del Rio, Carlos, Barb Dugelby, Brian Miller, Reed Noss, and Mike Phillips. “The Importance of Large Carnivores to Healthy Ecosystems.” Endangered Species Update, 18 (2001): 202–16.

[8] World Wildlife Fund. “Here Are Our Top 10 Facts about Jaguars.” WWF. Accessed May 3, 2024. https://www.wwf.org.uk/learn/fascinating-facts/jaguars.

[9] Ready, Alma. “Youths Who Shot Jaguar Face Mild Punishment.” The Arizona Republic. October 22, 1971: 28.

[10] Ready, 28.

[11] Ready, 28.

[12] Blakeslee, Sandra. “Gone for Decades, Jaguars Steal Back to the Southwest.” New York Times (1923-), Oct 10, 2006, 3-4, https://ezproxy.library.arizona.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/gone-decades-jaguars-steal-back-southwest/docview/93018188/se-2 (accessed May 5, 2024).

[13] Davis, Tony. “Did Jaguar Macho B Have to Die? Phoenix Zoo May Have Moved Too Fast to Euthanize Him, UA Pathologist Says.” Center for Biological Diversity, March 29, 2009. https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/news/center/articles/2009/arizona-daily-star-03-29-2009.html.

[14] Blakeslee, 4.

[15] Center for Biological Diversity. “Viva El Jefe! Arizona’s Famous Jaguar Lives, but What’s His Future?” Center for Biological Diversity, September 22, 2023. https://biologicaldiversity.org/w/news/press-releases/viva-el-jefe-arizonas-infamous-jaguar-lives-but-whats-his-future-2022-08-04/.

[16] Grant.

[17] Glenn, Warner. Eyes of fire: Encounter with a Borderlands Jaguar. Edited by Ray Turner. El Paso: Printing Corner Press, 1996, 7-9.

[18] Glenn, Plate 5.

[19] Brocious, Ariana. “In Arizona, Building a Wall – and Destroying a Canyon.” AZPM, October 30, 2020. https://news.azpm.org/p/news-splash/2020/10/30/183147-the-borderlands-boondoggle/.

[20] Miroff, Nick. “Where Trump’s Border Wall Left Deep Scars and Open Gaps, Biden Plans Repair Job.” The Washington Post, February 19, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2022/02/19/trump-biden-border-wall/.

[21] Samuel Chambers, et al, “Spatial Models of Jaguar Energy Expenditure in Response to Border Wall Construction and Remediation,” Frontiers in Conservation Science (Oct. 2022): 1-9

[22] Miroff.

[23] Northern Jaguar Project. “Our Mission.” NORTHERN JAGUAR PROJECT. Accessed May 3, 2024. https://www.northernjaguarproject.org/.