Nogal Trees, Mesquites, and Kino Heritage Trees in our High Desert Garden

McKinsey Tighe

Key Concepts

- Symbolism of walnut (nogal) tree in Santa Cruz County

- The resilience and versatility of mesquite trees

- The relationship between trees and human/wildlife health

- How uses of important tree species have changed over time

- The cultural and economic significance of fruit trees in Arizona

Key Terms

- Nogal – the Spanish word for “walnut tree”

- Riparian – environments near or made up of wetlands

- Native species – a species that originated and developed in a given area

- Drought deciduousness – a trait developed by plants that live in arid (dry) climates where they drop their leaves during periods of drought to conserve water

- Bosque – the Spanish word for “forest,” used to refer to dense tree coverage along streams and rivers

- Non-native species – a species that was introduced to a given area that originated and developed elsewhere

- Spanish missionaries – groups of Spanish colonizers who wanted to spread Roman Catholicism to Native Americans and establish settlements in areas of the Southwest U.S. and Mexico

- Heat mitigation – The process of reducing excess heat through methods such as transpiration by trees and reflection of sunlight; especially important in urban environments

RESEARCH ARTICLE

A4. What Are Some Important Tree Species in Santa Cruz County?

Nogal Trees, Mesquites, and Kino Heritage Trees in our High Desert Garden

McKinsey Tighe

Introduction

Have you ever sat under a tree to escape the hot sun, or had a delicious walnut brownie? Then you have benefitted from one of the tree species found in Arizona! Southern Arizona, including Santa Cruz County, is a region known for its diverse array of tree species that have impacted the area’s landscape, culture, and economy. From Arizona walnut trees to the mesquites, citrus, and fruit trees, each species has played a unique role in shaping the environment of Southern Arizona. This article will delve into the historical background, practical uses, and values of these prominent tree species in the region, shedding light on their cultural, ecological, and economic importance. Additionally, it will examine the ongoing conservation efforts led by organizations and community projects to protect these trees for future generations. Explore Southern Arizona’s beautiful world of trees, each with its distinct contribution to the region’s heritage.

Significance of Walnut Trees in Santa Cruz County

How did Nogales, Santa Cruz County’s historic seat of government, get its name? Look no further than the Arizona walnut tree (Juglans major), found in Southern Arizona and commonly known by its Spanish name, nogal. Arizona walnut trees can be identified by their pinnate compound leaves (growing on both sides of a central stem) and large green fruits, which ripen from dark brown to black between July and September, at which point they can be harvested and eaten.[1] Nogales was named as such because of the plentiful nogal trees around where the town was first founded in the 1880s – these Arizona Walnut Trees are still common within the town and the surrounding areas.

Figure 1: Arizona Walnut Tree containing unripe fruits (walnuts).[2]

Walnuts can be used in various dishes, from ice cream to cakes to salads and everything in between. They’re rich in protein and fats, making them a great snack or addition to any meal. The wood of Arizona walnut trees is used to make furniture like tables, chairs, and veneers (thin slices of wood used for furnishing), fence posts, and even gunstocks. They’re also significant to many tribes found in Arizona, especially the Apache people. The Apache and others incorporated walnuts into dishes like mesquite gravy, mixed them with alcohols like mescal, soaked walnut shells for dyes and paints, and built small lodges with the wood.[3] Arizona walnut trees are an important riparian species, meaning they’re often found along rivers and streams, including the Santa Cruz River. They’re nesting and breeding habitats for birds like acorn woodpeckers, and food sources for squirrels and other rodents. Arizona walnut trees are an icon of Southern Arizona and crucial to the development of Santa Cruz County.

Mesquite: The Wonder Tree

What tree do you associate most with Santa Cruz County and the rest of southern Arizona? There’s a good chance it’s a mesquite tree and for a great reason. Mesquite trees are one of the most abundant tree species found in Santa Cruz County. Arizona is home to three native species of mesquite, meaning these trees are found in and historically developed in the state. These include velvet mesquites (Neltuma velutina), honey mesquites (Neltuma glandulosa), and screwbean mesquites (Strombocarpa pubescens). They are drought-tolerant and require relatively little water to grow and thrive in most desert landscapes. Mesquites can conserve water by dropping their leaves during times of prolonged drought, a trait known as drought deciduousness. They’re able to extract water from deep within the soil by growing very long and two-tiered root systems, though this sometimes leads to the detriment of other vegetation.[4]

Mesquite fruits come in the form of legumes, which contain beans that can be harvested from May to June.[5] Nearly every part of the mesquite can be used to produce human goods, including its beans, leaves, and bark. Mesquite beans have been used for thousands of years by indigenous peoples like the Tohono O’odham; they’re commonly ground into flour for breads and cakes.[6] Today, mesquite beans are used to make coffee, pancakes, tortillas, ice cream, cookies, beer, etc., and are even preferred in some diets because they’re low sugar and gluten-free. Mesquite leaves are used to make teas, medicine, and balms to help with ailments like stomach aches and athlete’s foot. Mesquite wood is a primary source of lumber in the Southwest; historically it was used to build shelters by Native Americans and ships by Spanish settlers.[7] Today, it is often used to build furniture and for flooring in buildings, though mesquite wood has been used for anything from baskets to tools.

Figure 2: Mesquite flour made from mesquite pods.[8]

Mesquites are important to livestock like cattle and wild animals, including deer, javelinas, squirrels, and birds. Larger animals eat the seed pods that fall from the trees and use them for shade, while birds such as Gambel’s quail and Lucy’s warblers use the trees for nesting and breeding. Because the seeds are high in protein and fiber, they’re often recommended to farmers and ranchers for animal growth.[9] Mesquites make up an important community in the form of bosques (Spanish for “forest”), which have been threatened in recent years due to groundwater pumping and ranching activity.[10] Mesquites are an essential resource to the human and wildlife communities of the Southwest.

Figure 3: Lucy’s warbler foraging in a mesquite tree.[11]

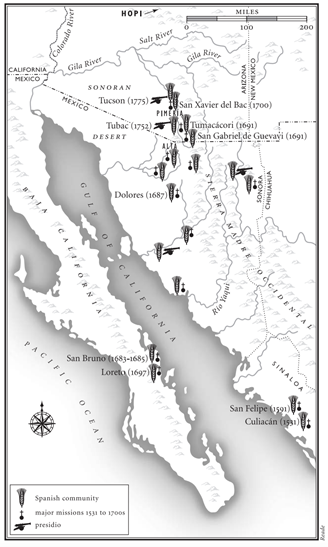

How Fruit Trees Became Part of Arizona Culture

Fruit trees have been a significant part of Arizona’s economies and communities for decades, despite being a non-native species (grown and developed in a region that’s not Arizona). How did these trees become such an integral part of culture in Santa Cruz County? Starting in the 1690s, Spanish missionaries (groups of Spaniards intending to spread Roman Catholicism to the Americas) brought many things to Arizona, including livestock, wheat, and fruit trees.[12] First brought to Arizona and the Mexican state of Sonora by Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, fruit trees were gradually weaved into the culture and economy of the state. Kino established Mission San José de Tumacácori in 1691 near what is now Nogales, Arizona, the land of which he deemed ideal for the growth of European crops. Fruits like peaches, pomegranates, and quinces flourished in the orchards of the mission, which helped lead to the vision of Arizona as a destination for aspiring agriculturists.[13]

Figure 4: A map showing the Spanish communities, major missions, and presidios (military settlements) in Southern Arizona and Mexico in the 16th-18th centuries. Padre Kino planted fruit orchards at Missions San Gabriel de Guevavi, Tumacácori, and San Xavier del Bac in the 1690s-1700s. Spanish troops later planted seeds from these trees at the Tubac and Tucson presidios . [14]

In the late 1800s, large amounts of citrus trees were planted in Salt River Valley near Phoenix, which helped kickstart citrus as an Arizona export. Citrus became so central to the Arizona economy around the time of its statehood that it even made it into the “5 C’s of Arizona” (Copper, Cattle, Cotton, Citrus, and Climate). The sunny nature and year-round growing season of Arizona made it ideal for many crops, as well as the relatively high availability of water and cheap land at the beginning of the 20th century. The availability of these farm jobs encouraged many Mexican families to migrate to the U.S. to work harvesting these citrus crops. However, as urban populations grew and water rights became increasingly complicated, citrus farms became less reliable, and production began to fall after the 1970s.

Figure 5: Lemon picking in Southern Arizona in the late 1950s.[15]

Today, citrus is still an agricultural staple of Arizona, but less so than in the previous century. Despite an economic decline, citrus and other fruit trees have not lost their significance in desert communities. Having fruit trees in your backyard is a great way to incorporate fresh produce into your diet; they also add aesthetic appeal to many areas of the state. There is no end to dishes and beverages that can be made with fruits that grow in Arizona, including lemonades, candies, and pies. Though not naturally found in the state, fruit trees have proven to unite communities in Arizona, provide an important boost to the economy, and add beauty to the landscapes of the Southwest.

Other Important Arizona Trees

Being a highly biodiverse region of the world, Southern Arizona is home to thousands of species, including many more tree species than just walnut, mesquite, and fruit trees. Another iconic Arizona species is the palo verde tree, which is the official state tree of Arizona. There are two species of palo verde native to the state, the blue palo verde and the foothill, or yellow, palo verde.[16] The primary difference between the two species is their trunk colors and growth locations; the former has a blue-green trunk and grows near water sources, while the latter has a yellow-green trunk and grows on rocky slopes. Palo verde trees are a significant source of heat mitigation in places like Santa Cruz County, which means reducing heat build-up. They help cool down surface and air temperatures through transpiration, which occurs when trees absorb water through their roots and release it from their leaves as water vapor. Planting more trees like the palo verde can help cool down urban desert areas, reduce heat-related deaths, and promote native vegetation.[17] Arizona is also home to four native oak species: Gambel, Emory, Arizona white, and Canyon live oaks.[18] The fruits of oaks, acorns, are also edible and can be consumed by humans with the right preparation. The leaves and fruits of each can be used to identify them, and you can use apps like iNaturalist and Apple’s Visual Look Up tool to help identify trees and other plants and wildlife in your area.

Efforts Towards Conservation and Longevity of Arizona Trees

There are many groups dedicated to protecting and cultivating trees in Arizona. The Kino Fruit Tree Heritage Project, named after Father Eusebio Francisco Kino, was started in 2003 by conservation organizations in Southeastern Arizona to help propagate fruit trees that can be traced back to those brought to Arizona by Spaniards in the 1700s, specifically those planted in the orchards of Mission Tumacácori.[19] Their ability to bring back these tree stocks lies in traditional Mexican horticultural practices according to Jesús Manuel García Yánez, a Mexican ecologist.[20] This project highlights the importance of connecting history with science; as Mr. García puts it, “a lot of it is not just collecting and propagating the tree, but collecting the stories behind the trees.” Another organization at the forefront of Southern Arizona tree protection is the Tucson Audubon Society, which recognizes the importance of trees in the lives of bird species found in Arizona. One of their programs builds nest boxes for Lucy’s warblers to place in mesquite trees that provide a safe habitat for the birds, who in turn disperse mesquite seeds and eat insects that may harm the tree.[21] Other conservation organizations like Friends of the Santa Cruz River and the Coalition for Sonoran Desert Protection are dedicated to promoting biodiversity in Southern Arizona and planting native trees to restore damaged ecosystems. Many of these conservation groups and projects rely on volunteers and local efforts, making them a great way to get involved in your community while also contributing to environmental protection.

Conclusion

The diverse tree species in Santa Cruz County serve as essential parts of the broader region’s ecosystem, culture, and economy. From the influence of Arizona walnut trees in shaping the town of Nogales, to the importance of mesquites providing sustenance and habitat for wildlife, to the economic contribution of citrus trees, each species plays a valuable role in the landscape. As this article has explored the background, practical uses, and significance of these prominent tree species, it is clear that they represent much more than vegetation – they are intertwined with the heritage and livelihood of Santa Cruz County. The ongoing conservation efforts by organizations dedicated to protecting and cultivating trees in Arizona highlight the importance of these natural resources for future generations. So next time you smell a hint of orange blossoms in the breeze or crack open a pomegranate, reflect on the centuries-long history of the trees that have brought these treats to you and their integral role in this beloved desert landscape.

Author Bio

McKinseyTighe is a University of Arizona student originally from McAlester, Oklahoma. She is currently a sophomore studying Natural Resources with an emphasis in Conservation Biology.

Bibliography

Brown, Claire. 2020. “Mesquite, crucial to Indigenous diets for centuries, works miracles with water and needs no fertilizer. Why don’t we grow more of it?” The Counter. https://thecounter.org/mesquite-arizona-wild-foods-foraging-sustainable-crop/.

“Ethnobotany of Mesquite Trees (U.S.” 2020. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/ethnobotany-of-mesquite-trees.htm.

Ragan & Massey. n.d. “Mesquite: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.” Wikipedia. Accessed April 21, 2024. https://www.raganandmassey.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/A-Job-Well-Done-Mesquite.pdf.

Sass, Sherry. 2004. “Mesquite Bosques: Not Just A Bunch Of Trees!” Wikipedia. https://friendsofsantacruzriver.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/mesquite_bosques.pdf.

Primary Documents:

Document 1:

“The Orange Lands of Sonora,” Tombstone epitaph. (Tombstone, Ariz.), 14 April 1888. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn95060905/1888-04-14/ed-1/seq-4/

[1] “Juglans major, Arizona Walnut.” 2017. Southwest Desert Flora. https://southwestdesertflora.com/WebsiteFolders/All_Species/Juglandaceae/Juglans%20major,%20Arizona%20Walnut.html.

[2] CK Kelly. 2018. iNaturalist observation. https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/15745115

[3] Heller, A. n.d. “Juglans major.” Trees and Shrubs Online. Accessed April 21, 2024. https://www.treesandshrubsonline.org/articles/juglans/juglans-major/.

[4] “Mesquite Trees: Pros & Cons for Your Landscape.” n.d. Titan Tree Care. Accessed May 4, 2024. https://titantreeaz.com/blog/mesquite-pros-cons.

[5] Schuch, Ursula K., and Jack J. Kelly. 2003. “Mesquite and Palo Verde Trees for the Urban Landscape.” Cooperative Extension. https://extension.arizona.edu/sites/extension.arizona.edu/files/pubs/az1429.pdf.

[6] Cappadona, Victoria. 2017. “Mesquite Beans: The Miracle Food.” Cappadona Ranch. https://cappadonaranch.com/blogs/blogs/mesquite-beans-the-miracle-food.

[7] “Camelback Mountain Wildlife – Phoenix.” n.d. Camelback Mountain. Accessed May 4, 2024. http://www.hikecamelback.com/camelback-wildlife.html.

[8] Ashley Landis. 2019. “Are mesquite beans the next gluten-free superfood?” Dallas Morning News. https://www.dallasnews.com/food/cooking/2019/11/04/are-mesquite-beans-the-next-gluten-free-superfood/.

[9] Ruiz-Nieto, J.E., Hernández-Ruiz, J., Hernández-Marín, J. et al. Mesquite (Prosopis spp.) tree as a feed resource for animal growth. Agroforest Syst 94, 1139–1149 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-020-00481-x

[10] Stromberg, J. C. “Riparian Mesquite Forests: A Review of Their Ecology, Threats, and Recovery Potential.” Journal of the Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science 27, no. 1 (1993): 111–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40023711.

[11] Steven Mlodinow. 2024. iNaturalist observation. https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/203816288

[12] “Citrus One of the 5 C’s of Arizona – HD SOUTH – Home Of The Gilbert Historical Museum.” 2020. Gilbert Historical Museum. https://hdsouth.org/citrus-one-of-the-5-cs-of-arizona/.

[13] Dunmire, William W. Gardens of New Spain: How Mediterranean Plants and Foods Changed America. 205-06. University of Texas Press, 2004. https://doi.org/10.7560/702714.

[14] Dunmire, William W. Gardens of New Spain, 197, Map 8.1.

[15] Ring, Bob. 2014. “Ring’s Reflections: Once a major growth industry, citrus’ future is uncertain here.” Arizona Daily Star. Accessed: April 21, 2024. https://tucson.com/news/local/east/rings-reflections-once-a-major-growth-industry-citrus-future-is-uncertain-here/article_799a927c-d346-5e49-bd2d-7ad0ee98c813.html.

[16] Pino, Melissa. 2023. “Palo Verde Tree: Description, Types, Facts, and Care Tips.” Planet Natural. https://www.planetnatural.com/palo-verde-tree/.

[17] “Using Trees and Vegetation to Reduce Heat Islands | US EPA.” 2023. Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/heatislands/using-trees-and-vegetation-reduce-heat-islands.

[18] “Native Oak Trees.” 2023. Cooperative Extension. https://extension.arizona.edu/sites/extension.arizona.edu/files/attachment/NativeOakTrees.pdf.

[19] “Kino Heritage Fruit Trees.” 2020. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/kino-heritage-fruit-trees.htm.

[20] Michael Tortorello, “Seeds of an Era Long Gone,” New York Times (Nov. 21, 2012),

(https://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/22/garden/in-tucson-a-search-for-fruit-the-missionaries-knew.html)

[21] “Lucy’s Warbler ⋆ Tucson Audubon.” n.d. Tucson Audubon. Accessed May 4, 2024. https://tucsonaudubon.org/lucys-warbler/.