Special Focus A – Buffalo Soldiers On The Border

John P. Langellier, Ph.D.

Introduction

The African American soldiers sent by the U.S. Army to “win the west” from Apache peoples and guard the U.S.-Mexico border left a profound impact in communities like Santa Cruz County. These were the legendary Buffalo Soldiers, one of the most unique aspects of the history of Santa Cruz County and the U.S.-Mexico border region.

Before the U.S. Border Patrol’s founding in 1924, Buffalo Soldiers and other U.S. Army troops guarded the border with Mexico. In the process, many African American military personnel made contributions to Santa Cruz County. Some of them served in Nogales. This included Sergeant Charles Mingus Sr., the father of legendary jazz composer Charles Mingus, Jr. The Minguses along with other Buffalo Soldiers lived in Camp Little, once located along Western Avenue in Nogales.

Civil Wars Origins and Fighting on the Frontier Against the Apache

During the Civil War (1861-1865), nearly 180,000 African American men joined the Union Army and Navy. In 1866, their valor inspired the U.S. Congress to authorize segregated U.S. Army units comprised of African American enlisted personnel. By the 1870s, some Native Americans nicknamed these men “Buffalo Soldiers” possibly because they thought the troops resembled buffalo. For more than thirty years, Black soldiers performed on the frontier. This included Arizona where they fought in the U.S. Government’s war against the Apache under Geronimo. From that time until decades into the twentieth century, African American troops became a familiar sight in Arizona, with Fort Huachuca in Cochise County being the Buffalo Soldiers’ most important base in our region.

Military Vigilance During the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920)

Years after determined Apache residence ended, revolution in Mexico (1910-1920) opened a decade of new conflicts. The Mexican Revolution first began as a rebellion against Mexico’s longtime dictator Porfirio Díaz, but after his exile the Mexican republic fell into chaos as rival political groups fought for power and control of important cities. Bordertowns like Nogales, Sonora, were cities the revolutionaries fought for control of. This violence occasionally threatened the United States. Concerned for the safety of U.S. citizens and their property, U.S. government officials responded by sending the Buffalo Soldiers to the border.

Black soldiers played an important role at the border as U.S.-Mexico tensions remained high over the following years, especially after Mexican revolutionary Francisco Villa’s troops attacked the border town of Columbus, New Mexico, in March 1916. Many Buffalo Soldiers, including the Tenth Cavalry, participated in the 1916-1917 U.S. Army invasion of the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, in an attempt to arrest or kill Villa. The capture of several Buffalo Soldiers by Mexican troops almost led to war between the U.S. and Mexico. Ultimately, the U.S. Army withdrew from Mexico without finding Villa and the Buffalo Soldiers returned to guarding the border as the U.S. entered World War I.

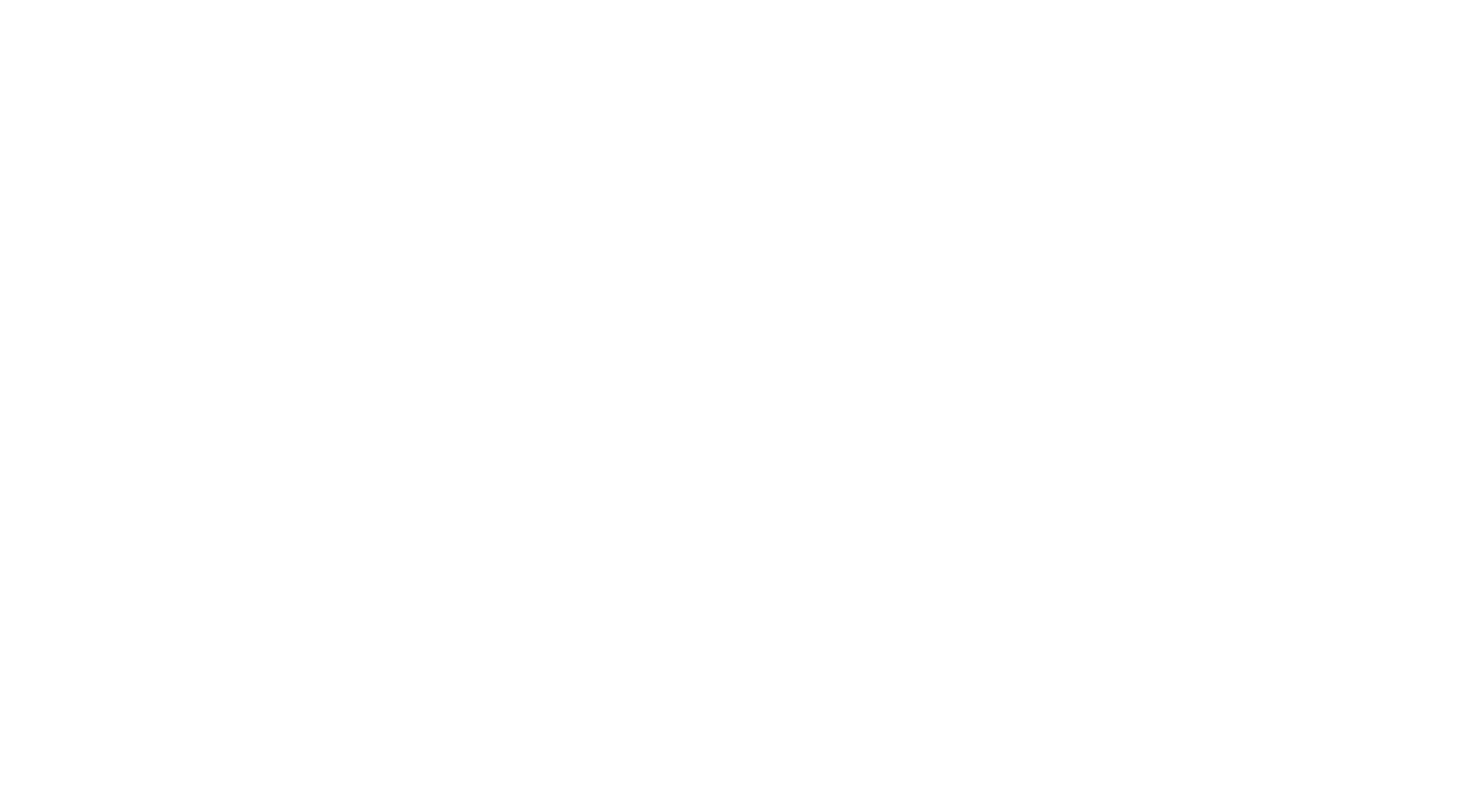

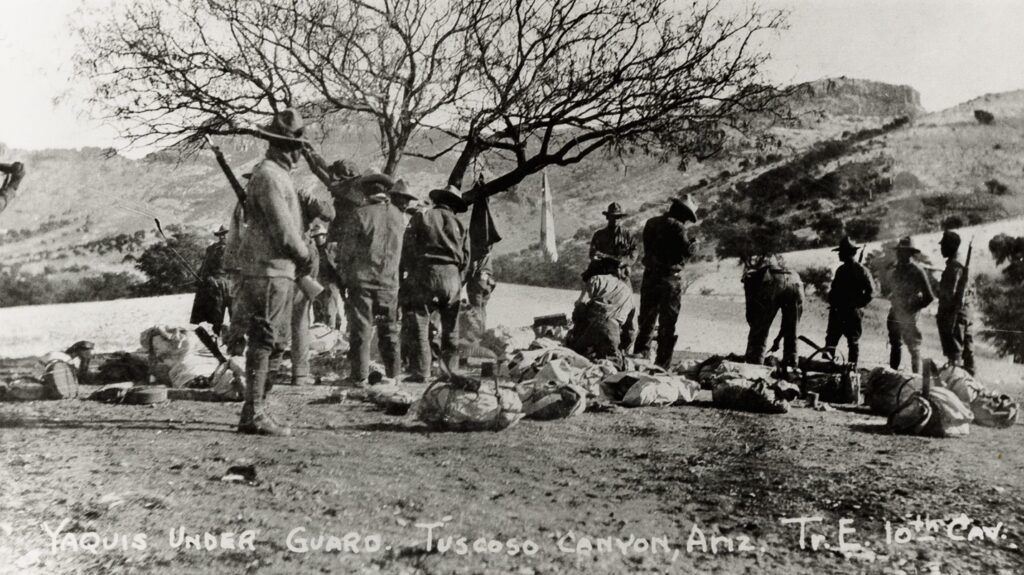

During that time, Buffalo Soldiers in Santa Cruz County fought one of the very last battles between the U.S. Army and indigenous peoples. On January 9, 1918, 10th Cavalry troops encountered thirty members of the Hiaki or Yoeme people (today popularly referred to as the Yaqui), who illegally entered the U.S. from Mexico. The starving people, long persecuted by the Mexico government, sought food and refuge within Western Santa Cruz County’s rugged Atascosa/Tumacácori Mountains. In an area along Bear Valley known as Tuscoso Canyon, the Yaqui opened fire on Troop E, Tenth Cavalry.

Although outnumbered, the small Yaqui force fought fiercely. Eventually, they lost the skirmish to the Buffalo Soldiers. One of their men died of fatal wounds. Tenth Cavalry troopers arrested the survivors and captured their weapons, a small hodgepodge of Winchesters and Mausers. Later, a federal grand jury in Tucson indicted nine of the captives for transporting weapons into the United States. However, a sympathetic judge sentenced them to only 30 days in the Pima County jail possibly because of concern that their deportation could result in virtual enslavement or execution in Mexico.

While many Buffalo Soldiers wished they could be in Europe along with the rest of the predominantly white U.S. Army fighting in World War I, African American troops in Santa Cruz County and the rest of the border still faced danger. The most dramatic incident the Buffalo Soldiers in Santa Cruz County experienced was a fierce clash against Mexican combatants on August 27, 1918, in Nogales. Bisbee’s Daily Review newspaper reported: “The fighting followed alleged efforts of a Mexican custom officer to smuggle a fellow countryman across the boundary into the United States. An American sentry attempted to stop him. The two Mexicans fired at the sentry across the street, striking him in the right arm.” This was the Battle of Ambos Nogales, known in Mexico as la batalla del 27 de agosto.

Soon, the duel involved the U.S. Army’s Thirty-Fifth Infantrymen and Black Tenth Cavalrymen. When the confrontation ceased, twenty-nine Americans sustained wounds, and seven U.S. soldiers died. At the very least, Mexican dead included thirteen persons, including the mayor of Nogales, Sonora. This encounter finally ended intermittent warfare in Southern Arizona as the age of Indian Wars and Mexican Revolution closed.

Camp Little’s Garrison

Despite occasions of combat, Buffalo Soldiers usually led routine lives. Besides offering security for U.S. border residents, the area’s African American soldiers contributed to the local economy both in Arizona and in Sonora. Additionally, Black troops participated in patriotic parades and other holiday celebrations. Often, they provided musical concerts to entertain fellow soldiers and citizens alike.

Camp Little’s Buffalo Soldiers also staged sporting events. The last activity particularly brought Nogales civilians and the military together. In fact, the Twenty-Fifth Infantry baseball team—The Wreckers—regularly drew crowds to enjoy top talent from the regiment. Some of these players, such as Wilbur “Bullet Joe” Rogan, went on to careers with the storied Negro Leagues (the professional teams African American baseball players were restricted to during the age of racial segregation). These amateurs occasionally even faced and defeated all stars from the major leagues!

Despite a general acceptance, Black troops sometimes experienced prejudice. Although not as prevalent as that faced elsewhere in the nation, particularly in the American South where “Jim Crow” laws harshly discriminated against Blacks by mandating racial segregation. Tragically, African Americans were often victims of lynchings and other violence. Among the significant signs of bias in Arizona were laws that prohibited racial intermarriage between whites (referred to as “Caucasians”) and Blacks, Native Americans, and certain other ethnic groups. During 1919, this statewide racist ban caused the Santa Cruz County clerk to refuse “over a hundred couples marriage licenses.” As the July 27, 1919 edition of the Tombstone Epitaph indicated, by law African American men only could wed Native Americans, or Mexican women of Native American ancestry. African American men could not marry Caucasians or Latinas without Native American heritage. The same newspaper revealed that over “the past year, 250 licenses” had been issued to Blacks in the county, most of which had been obtained by soldiers.

Santa Cruz County Buffalo Soldiers

During their tours of duty in Santa Cruz County, a growing number of Buffalo Soldiers began families. Among them was Sergeant Charles Mingus, Sr. Of mixed parentage (having a Black father and white mother) family lore held that young his dislike of the South Carolina plantation where he was born prompted him to run away and join the army. Supposedly, on November 5, 1892, Mingus first enlisted at Richmond, Virginia. From there, Private Mingus reported to the Tenth Cavalry. By March 14, 1897, he had advanced to corporal in Troop G of the regiment. After a brief stint as a civilian, he, reenlisted in the Army. This time he went to the Twenty-Fourth Infantry. After that, he traveled widely, eventually being sent to Nogales’s Camp Little.

Charles Mingus, Sr.’s long military career ended in Nogales on a high note reflective of the larger Buffalo Soldier heritage in Santa Cruz County. In 1920, as a sergeant, he earned his commanding officer’s praise for successful efforts completing the Ali Baba, Camp Little’s first movie theater. The theater’s civilian contractor halted the project after funding ran low. Undeterred, according to a December 20, 1920, Nogales Daily Oasis article Sergeant Mingus promptly took “charge of the work, superintended it and prosecuted it to a conclusion.”

On April 22, 1922, Sergeant Charles Mingus and his spouse Harriet Sophia Philips added to the story. On that day they welcomed their son Charles, Jr. into the family. While some other descendants of Black military members followed in their elders’ footsteps, young Charles forged a different destiny. Rather than enlist, the sergeant’s talented son achieved fame as a renowned jazz musician and composer. In fact, his The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady (1963) still is regarded as one of the greatest jazz records of all time.

Famous or unknown, the offspring of Black soldiers formed a special part of the Camp Little history. Happily, each year, decedents now celebrate their ancestry and the accomplishments of those who came before them through the Nogales Buffalo Soldiers Legacy Association. According to the group’s website, their mission is dedicated to: “partner with schools and communities across the nation to educate, inform and highlight the notable accomplishments of the Buffalo Soldiers who served patriotically while subjected to oppressive and discriminatory conditions.”

Their goals offer a way to understand past discrimination bravely faced by Buffalo Soldiers in Santa Cruz County and elsewhere. These soldiers often fought a more daunting battle than with rifles and machine guns. The Buffalo Soldiers’ examples to combat prejudice pointed the way for later generations to achieve a more equitable future for all.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bisbee’s Daily Review August 28, 1919

Finley, James P. “The Buffalo Soldiers at Fort Huachuca.” Huachuca Illustrated: A Magazine of the Fort Huachuca Museum 1 (1993): 42-77; 2 (1996): 1-4, 9-19.

Glass, E.L.N. Comp and Ed. The History of the Tenth Cavalry, 1866-1921. Fort. Collins, CO: Army Press, 1972.

Hardaway, Roger D. “UNLAWFUL LOVE: A History of Arizona’s Miscegenation Law.” Journal of Arizona History 27 No. 4 (Winter, 1986): 377-390.

Horne, Gerald. Black and Brown: African Americans and the Mexican Revolution, 1910-1920. New York: NYU Press, 2005.

Langellier, John P. More Work Than Glory: The Buffalo Soldiers in the United States Army, 1866-1916. Warwick, UK: Helion & Company, 2023.

nogalesbuffalosoldiers.org.

Nogales Daily Oasis December 20, 1920.

Santoro, Gene. Myself When I am Real: The Life and Music of Charles Mingus. Oxford University Press, 1994.

Tombstone Epitaph July 27, 1919

Wharfield, H.B. 10th Cavalry & Border Fights. El Cajon: Wharfield, 1965.

Work, David K. “Enforcing Neutrality: The Tenth U.S. Cavalry on the Mexican Border, 1913- 1919.” Western Historical Quarterly 40 No. 2 (Summer 2009): 179-200.