The Unbelievable Origins of Rio Rico

Daisy Olivera, University of Arizona

Key Concepts:

- Rio Rico’s population has expanded over recent years, becoming larger the City of Nogales as of the 2020 U.S. Census

- Rio Rico’s historic heritage is defined by its early indigenous past, Hispanic influence through missions, the Calabasas townsite as Rio Rico’s origin point, and the Baca Float #3 fraud

- Since the 1970s Rio Rico has developed as an unincorporated suburban community, although its future is still uncertain amid different business development plans

Key Terms:

- Suburb: a community outside of a city

- Bedroom Community: a suburb where most of the population commutes to another city for work

- Ethnicity: a group of people who identify each other through shared cultural practices

- Pimeria Alta: (Upper Pima Land); the historic name for the region of southern Arizona and northern Sonora given by the Viceroy of New Spain (colonial Mexico)

- San Cayetano de Calabasas: Spanish mission established in 1691 by Father Eusebio Kino near Tumacácori

- Land Grant: an allotment of public land, especially to an institution, organization, or a certain group of people

- Baca Float #3: the 100,000 acre award of land the U.S Government gave to businessmen claiming to be the heirs of the Luis Maria Baca family of New Mexico in 1864 which includes all of modern-day Rio Rico, Tumacácori, and the former town of Calabasas

- Gulf American Corporation (GAC): land development company from Florida

B6. What is Rio Rico’s History as Santa Cruz County’s Suburb?

The Unbelievable Origins of Rio Rico

Daisy Olivera, University of Arizona

Introduction

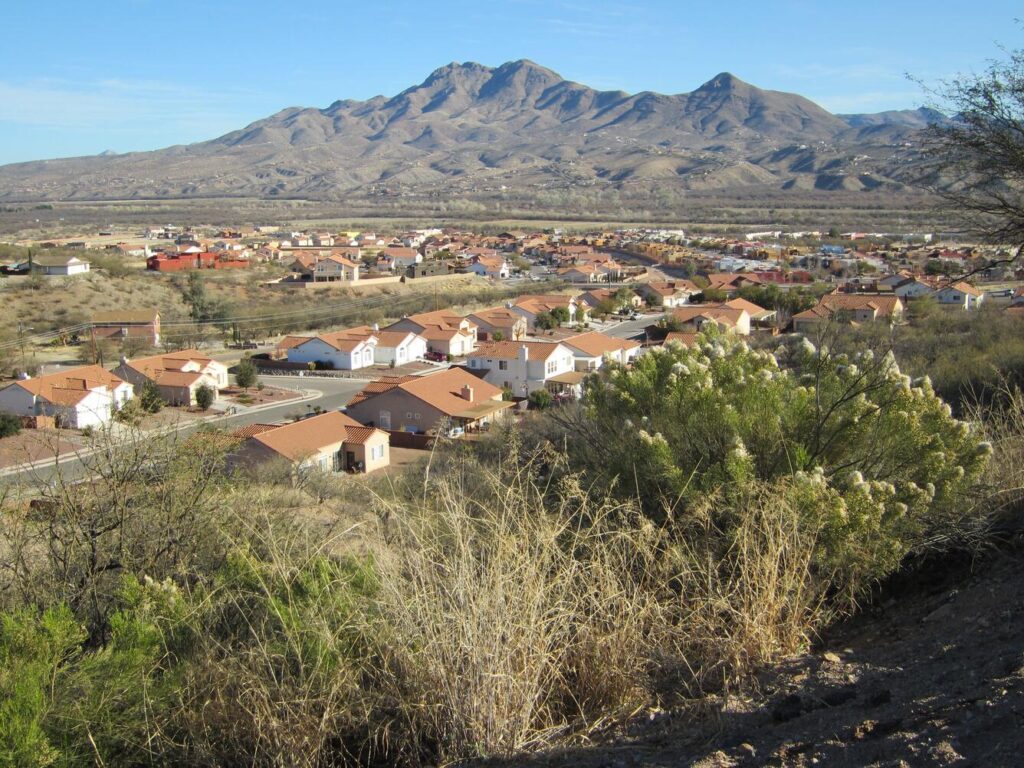

Situated near the foothills of the San Cayetano mountains north of Nogales lies the overlooked yet lively community of Rio Rico. As a suburb, Rio Rico has plenty to offer and has a rich history that is not really known. Before officially being renamed in the 1960s, the community was known as Calabasas, a prosperous town with saloons and a railway that allowed transnational trade. Located in what is now southeastern Rio Rico, Calabasas became a ghost town and faded away into history. Despite its shaky past, Rio Rico is growing rapidly, becoming Santa Cruz County’s largest population center since 2020.

Population Demographics

Rio Rico is a suburb of Nogales and is mostly known as a bedroom community, a suburb where most of the population commutes to another city for work. However, Rio Rico has expanded in population over the past several years. Rio Rico has about 20,000 people living within the town, exceeding the number of residents living in Nogales. Nogales’s growth rate was at 0.23% in 2021 while Rio Rico is constantly growing at a staggering rate of 12.8% according to the 2020 U.S Census. According to that same census, 87% of Rio Rico residents are of Hispanic/Latino ancestry. Other significant information on race and ethnicity indicates 11% of Rio Ricans are non-Hispanic Whites, 0.41% are Native Americans.[1]. The average age median in Rio Rico is around 34 years old for male residents and 33 years old for female residents.

With the growing population, Rio Rico’s unemployment has also risen to a rate of 6.45% by 2021. Rio Rico’s location near the large commercial port of entry between the two nations in Nogales has allowed employment to grow dramatically. Employment in Rio Rico varies in multiple sectors with office and administrative jobs being the highest at 15.6%. Other common jobs that Rio Rico residents work are sales and operations (12.2%), healthcare (6.17%), law enforcement (5.0%), and many more.

Early History of Rio Rico

Rio Rico’s history begins with the indigenous people who lived along the Santa Cruz River centuries ago. The Hohokam and their descendants, the O’odham (oh-ohd-ham) were one of many indigenous groups who lived in region Spanish colonists called the Pimeria Alta (northern Sonora and southern Arizona). Also living near the O’odham (called Pimas or Papagos by the Spanish) were the Sobaipuri, and the Apache. Along the Santa Cruz River, the O’odham and other indigenous people practiced agricultural methods such as irrigation and crop farming. They also built settlements in the area such as Toacuquita and Tumacácori which was an O’odham village before the Spanish arrived in the area.[2]

Although Spanish explorers had surveyed what became Rio Rico since the 1540s, it was not until the 1690s that permanent Hispanic settlement arrived in the Santa Cruz River Valley. Starting in January 1691, the Spanish created Catholic mission church communities through the work of Father Eusebio Kino. After meeting with the O’odham and the Sobaipuri, Kino established three missions in or around Rio Rico: Tumacácori, Los Santos Angeles de Guevavi, and San Cayetano de Calabasas. Located in what is now southeast Rio Rico, Mission San Cayetano de Calabasas was an extension of Tumacácori that served as a stock ranch and had a small chapel.[3] San Cayetano de Calabasas was the only mission amongst the three to not be in close proximity to the Santa Cruz River. Instead, it was built above the valley floor on a rocky ridge which provided necessary vigilance to the mission.

Indeed, the missions occasionally experienced abandonment after violent conflict between the Spanish colonists and the indigenous people such as the 1751-1752 Pima Revolt by the O’odham. The original mission was abandoned and then rebuilt at its current site in 1753. Eventually even the community at the rebuilt Mission San Jose de Tumacácori eventually moved out of the region due to constant attacks from the Apache. Mission San Cayetano de Calabasas was abandoned by the O’odham and the Spanish in 1786 and continued to be used as a stock ranch between the years of 1807 and 1830. Vaqueros (cowboys) of different cultural backgrounds worked the land despite the constant hostility from the Apache. In 1844, the mission was sold to Manuel Gandara, governor of Sonora, for about $500, which is about $17,843 dollars in the present day. Several years later, Calabasas became into the United States after the Gadsden Purchase of 1853.

After it became U.S soil, the area where the town of Calabasas was founded was sold to Colonel Charles P. Sykes, a Californian. Before its purchase, Calabasas only had a general store, a polling place, and a post office due to its close proximity to Fort Mason (a U.S. Army post stationed at the former Calabasas mission). Calabasas also consisted of ranches that supplied hay to Fort Mason, with Elias Pennington having his family become the first permanent White American residents of Arizona in the 1850s. Colonel Sykes purchased Calabasas in 1878 and established the Calabasas Land and Mining Company. The construction of a railroad in the area a few years later made Sykes’s gamble worth it. The 1882 opening of the “New Mexico and Arizona Railroad” by East Coast investors crossed right through Calabasas as it connected the growing U.S railroad network with Mexico for the first time via Nogales. Before Nogales became Santa Cruz County’s main city, Calabasas was the area’s “boom town” with sixteen saloons, three hotels, the most known being the Santa Rita hotel, and even a U.S customs house[4]. Calabasas at the time would be known as “Hell’s Hollow” due to the amount of violence that occurred surpassing the violence of even Tombstone, the town “too tough to die”. Like every boom town, Calabasas’s population declined from 800 residents to none due to many moving north to Tucson or out of the state around 1913.

Violence against Families in the Santa Cruz Valley

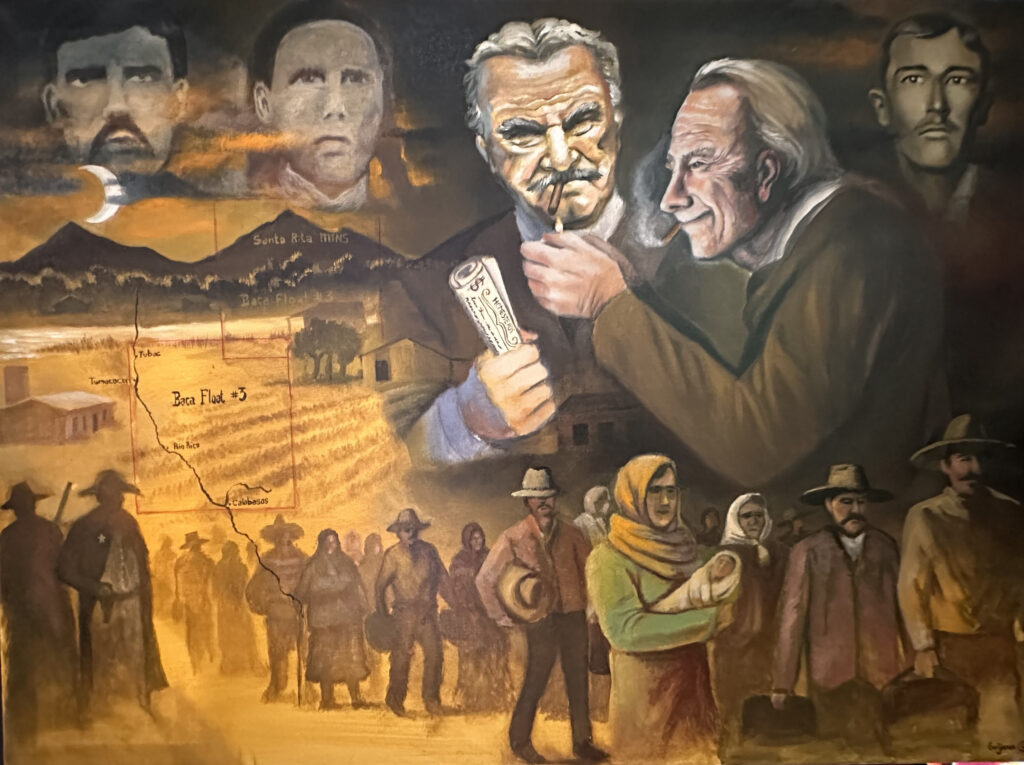

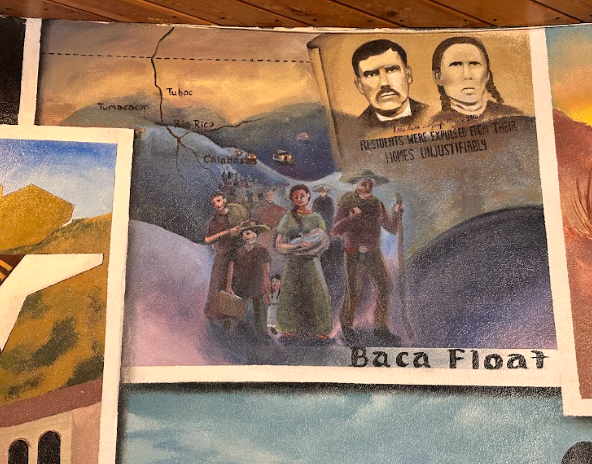

Miguel Grijalva (2024), Oil on Canvas

To make this story more complicated, during that time there was a dispute over who legally owned the land where Rio Rico is located. Although Sykes bought the land for the town of Calabasas, businessmen claiming to be the heirs a Hispanic family in New Mexico, the Bacas, claimed ownership of the entire Santa Cruz River valley as their own land. Indeed, in 1864 the U.S Government awarded 100,000 acres in what became Rio Rico to the Baca Family as compensation for land their father, Luis Maria Baca, lost in a complicated land dispute in Northern New Mexico many decades prior. Baca Float #3, one of the five gifts of land the U.S government gave to the Bacas, was quickly bought by out of state businessmen who engaged in land fraud. A long legal dispute over the land’s ownership began. Many Mexican and White Americans unknowingly started small farms or homesteads within the Baca Float #3 and raised families there for decades while the case dragged on.

Finally in 1917, the U.S Supreme Court confirmed that the businessmen, not the local ranching families, owned the lands of the Baca Float #3 land grant. The court also ordered the ranching families living in the Rio Rico/Tumacacori area to move elsewhere.[5] Many of these families refused to leave and were forcibly removed by U.S marshals and were left impoverished and with nowhere to go. As a response the U.S Congress passed a law in 1921 titled An Act for the Relief of Settlers which allowed the displaced Mexican and White families to move to Buckeye, Arizona, an agricultural area west of Phoenix. According to Steve Gastellum, a historian and descendant of a family evicted from Baca Float #3, it’s not clear how many people, if any, benefitted from the law.

Modern Development

Despite the violent fraud, Baca Float #3 was eventually sold to a Floridian company named the Gulf American Corporation (GAC) in 1967 by Tol Pendleton, a previous owner of the Float. This was considered the largest land boom in Arizona. The Gulf American Corporation was one of the largest land companies in the state of Florida. In 1966, the GAC planned to develop what is now known as Rio Rico, with a budget of $150 million dollars. Rio Rico’s center was approved to have 8,900 acres to be zoned. Back in Florida, the GAC was aggressively marketing land sales in the United States and foreign countries. Instead of waiting for a buyer, the GAC would bring in people from elsewhere to Florida for property sales. They skipped over Florida’s required property reports and practiced lot switching, a practice where property owners changes property lines that already exist.[6] The GAC was found guilty of fraudulent practices[7] in Florida and Santa Cruz County oversaw the charges against the GAC, with Ronald Sandler, director of Rio Rico for the GAC stating that no formal charges were leveled.

In more recent years, Rio Rico has expanded with more people moving into the region. This has allowed more businesses and produce companies to allocate their companies for labor. With a growing population and tourism, there had been proposed plans to create a “vitality district.” The Vitality District plan would allow Rio Rico residents to stay in town without having to travel to Nogales for necessities and entertainment.[8] It would make Rio Rico more accessible with public transportation, sidewalks, and plazas. The Vitality District would also have more entertainment and dining businesses, as well as natural areas, hiking trails, and parks to enjoy the natural landscape of Rio Rico.

Conclusion

Rio Rico has a rich history that is still yet to be explored. From the indigenous people that lived along the banks of the Santa Cruz River, the Spanish missions of San Cayetano de Calabasas, the old west boom town of Calabasas to the modern-day name change and development, Rio Rico has plenty to boast about.

About the Author

Daisy Olivera is a Nogales native who is currently attending the University of Arizona as an undergrad history major.

Bibliography

“Rio Rico, AZ | Data USA.” n.d. Datausa.io. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/rio-rico-az/.

“Tumacacori’s Yesterdays:Jesuit Pioneering.” n.d. Npshistory.com. Accessed April 25, 2024. http://npshistory.com/publications/tuma/jackson/chap1.htm.

Garate, Donald. 2000. San Cayetano de Calabazas: An Important and Informational Guide to the Calabazas Mission. Edited by Anita Badertscher. Tucson: Western National Parks Association.

Trujillo, Manny . n.d. Oral History of Rio Rico. Rio Rico Historical Society. Accessed April 14, 2024.

Sheridan, Thomas E. “Rio Rico and the Great Arizona Land Rush.” Journal of the Southwest 48, no. 1 (2006): 1–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40170312.

“Rio Rico Vitality District Master Plan.” 2023. Santa Cruz County. February 2, 2023. https://www.santacruzcountyaz.gov/DocumentCenter/View/17819/RRVD-Master-Plan-Report.

Notes

[1] “Rio Rico, AZ | Data USA.” n.d. Datausa.io. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/rio-rico-az/.

[2] “Tumacacori’s Yesterdays:Jesuit Pioneering.” n.d. Npshistory.com. Accessed April 25, 2024. http://npshistory.com/publications/tuma/jackson/chap1.htm.

[3] Garate, Donald. 2000. San Cayetano de Calabazas: An Important and Informational Guide to the Calabazas Mission. Edited by Anita Badertscher. Tucson: Western National Parks Association.

[4] Trujillo, Manny . n.d. Oral History of Rio Rico. Rio Rico Historical Society. Accessed April 14, 2024.

[5] Mattison, Ray H. “THE TANGLED WEB: The Controversy Over the Tumacácori and Baca Land Grants.” The Journal of Arizona History 8, no. 2 (1967): 71–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41695413.

[6] Sheridan, Thomas E. “Rio Rico and the Great Arizona Land Rush.” Journal of the Southwest 48, no. 1 (2006): 1–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40170312.

[7] Sheridan, Thomas E. “Rio Rico and the Great Arizona Land Rush.” Journal of the Southwest 48, no. 1 (2006): 1–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40170312.

[8] “Rio Rico Vitality District Master Plan.” 2023. Santa Cruz County. February 2, 2023. https://www.santacruzcountyaz.gov/DocumentCenter/View/17819/RRVD-Master-Plan-Report.