Spanish and Mexican Arizona (1540-1854)

Jacey Demaree, University of Arizona

Key Concepts:

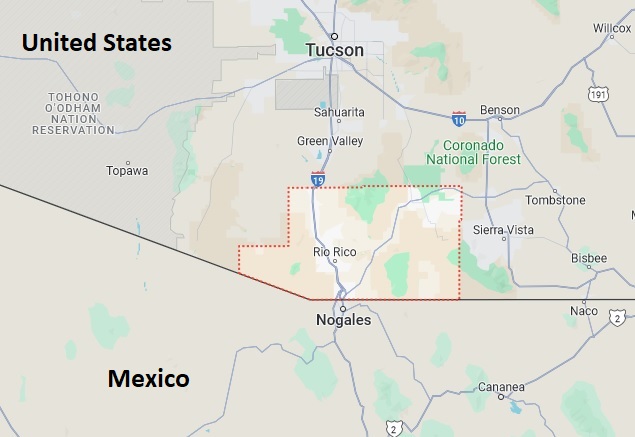

- Santa Cruz County is one of Arizona’s two Latino-majority counties as of 2020, with a Hispanic/Latino presence dating to the 1540s.

- Catholic missionary work in the 1600s-1700s expanded Southern Arizona’s Hispanic/Latino presence.

- Mission Tumacácori was founded in the Santa Cruz River Valley by Jesuit Father Eusebio Francisco Kino in 1691. The goal of the mission was to promote Christianity by converting the Indigenous Tohono O’odham people to Catholicism.

- Indigenous communities often resisted both Spanish/Mexican colonists and the Apache Indians. Resistance consisted of revolts, such as the Pima Revolt in 1751 that caused the Spanish Empire to establish a presidio (or fort) in Tubac.

Key Terms:

- Hispanic – a person of Spanish-speaking ancestry and the culture shaped by the Spanish colonization of the Americas; in this article, this term refers to Southern Arizona’s historic Spanish-Mexican peoples and their culture before 1854 when the region became part of the United States.

- Latina/o – a modern-day person of Spanish-speaking ancestry in the U.S., including Mexican Americans. This is now the term most often used by the U.S. Government and community groups to describe people of Spanish-speaking ancestry, including Mexican Americans

- Colonization – the political and economic control of a people or area by another nation.

- Mission – an organized effort to spread the Christian faith.

- Jesuits – members/priests of the Society of Jesus, a Roman Catholic order of religious men. Known for their missionary work in the Americas and Asia.

- Pima Revolt – an armed uprising by the Tohono O’odham against Spanish colonists and missionaries in Southern Arizona/Northern Sonora from November 1751-March 1752. As a consequence, the Spanish founded the Tubac Presidio (fort) in 1752.

- Besiege – to surround with armed forces to take control or capture.

- Presidio – A Spanish military fort.

RESEARCH ARTICLE

B2. What are the roots of Santa Cruz County’s Hispanic Heritage?

Spanish and Mexican Arizona (1540-1854)

Jacey Demaree, University of Arizona

Introduction

Located on the U.S.-Mexican border, Santa Cruz County is one of two Latino-majority counties in Arizona and has the state’s largest proportion of Hispanic residents. According to the 2020 U.S. Census, 83% of Santa Cruz County residents are Latina/o. About 79% of county residents speak Spanish. The area’s Hispanic/Latino heritage, dating back to the mid-1500s, is key to understanding Santa Cruz County’s modern-day culture and future.

The Beginning of Hispanic Culture in Southern Arizona

When exploring Santa Cruz County’s Hispanic heritage and future, it is important to note the terms used to describe this history. The terms Hispanic and Latino are often used interchangeably, but depending on who you ask around the U.S., these terms may mean different things.

In this article, Latina/o refers to current-day people of Spanish-speaking ancestry living in the U.S., including Mexican Americans. This is now the term most commonly used by the U.S. Government and community groups to describe people of Spanish-speaking ancestry. Hispanic refers to a person of Spanish-speaking ancestry and the culture shaped by the Spanish colonization of the Americas, including the historic Spanish-Mexican peoples of Southern Arizona before the region became part of the United States in 1854.

In the century before the English and Pilgrims founded the Virginia and Massachusetts colonies, the Spanish Empire was already beginning to take control of what is now the U.S. Southwestern borderlands. The first official Spanish explorations into Southern Arizona, mainly in search of gold and other resources, took place in 1539-1540. Francisco Vasquez de Coronado’s group of conquistadores (conquerors) were the most famous of these explorations.

However, it was not until the 1690s that the Spanish began a more systematic colonization of this region. Colonization is the political and economic control of a people or area by another nation. In this case, the Spanish were colonizing the Indigenous peoples of what are now Arizona and the Mexican state of Sonora. Hispanic culture was planted in Santa Cruz County by the Catholic missions created by Jesuit priests sponsored by the Spanish King. A Mission is an organized effort to spread the Christian faith, in this case among the Indigenous Tohono O’odham people of Arizona.

The priests who founded the historic missions of Sonora and Arizona were Jesuits, members of the Roman Catholic Church’s Society of Jesus. As representatives of the Spanish King, the Jesuits worked to spread and even force Catholicism on the Indigenous people of Sonora and Arizona. The missionary project aided in Spanish colonization and the establishment of settlements in present-day Southern Arizona.

Father Eusebio Francisco Kino was an important figure in the missions, founding the Tumacácori mission in 1691. Father Kino was praised by his peers, such as Miguel Venegas, a Jesuit administrator, for moving the native Tohono O’odham people into towns near missions and subjecting them to agricultural labor to facilitate their conversion.[1] Missionaries and Spanish settlers viewed the Indigenous people as uncivilized heathens in need of their guidance. Many people of the Tohono O’odham tribe converted, participated in planting, built adobes, baptized their children, and began speaking Spanish.

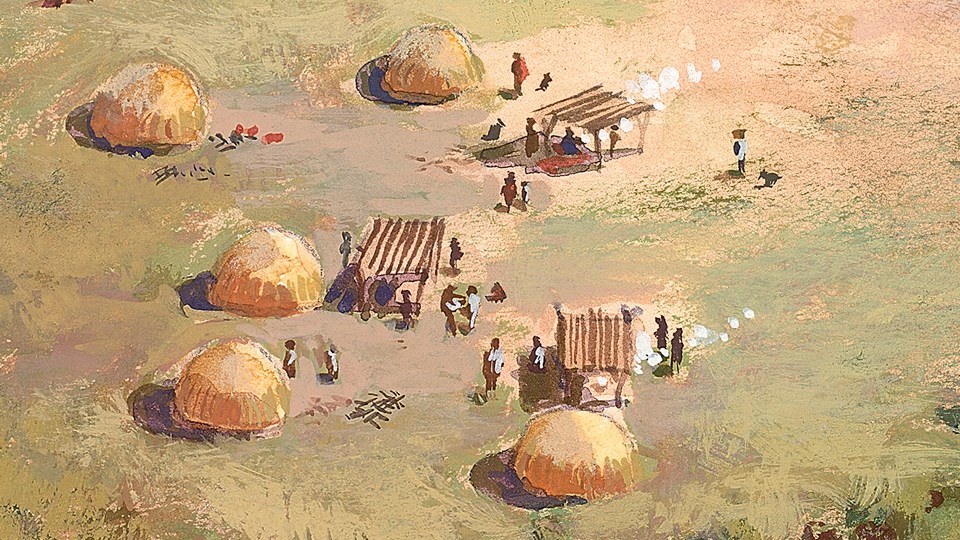

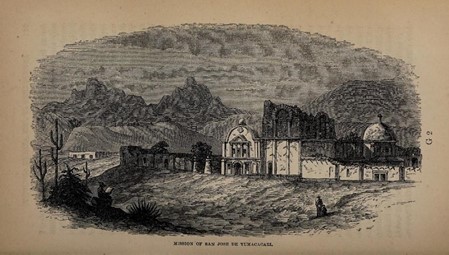

Figure 1: A drawing of the Tumacácori mission made during the period of 1821-1869, in a state of slight deterioration. Illustrated by an American journalist and traveler.[2]

Hispanic settlement was sparse in Southern Arizona until the discovery of silver in 1736 at a canyon called “Arizona” southwest of Nogales, Sonora. The name for the state of Arizona comes from this Spanish colonial mining site.[3] A huge increase of Spanish settlers moved to the Santa Cruz Valley in hopes of profiting off the silver mines. As more settlers arrived, the O’odham population began declining amid overwork at the missions and death from exposure to European diseases. The influx of settlers and decreasing populations created tension for the Indigenous converts.

Resistance to Spanish Presence and Tubac Presidio

As the Hispanic newcomers drastically changed their way of life, the Tohono O’odham tribe resented both settlers and missionaries, leading to the Pima Revolt. Fought between November 1751-March 1752, the Pima Revolt was an armed uprising by the Tohono O’odham against Spanish colonists and Jesuit missionaries in Southern Arizona/Northern Sonora. During the revolt led by Luis Oacpicagigua, the O’odham killed over a hundred Spaniards and burned the church at Tubac along with the Jesuit priest’s home. Spanish authorities realized they needed more protection and decided to build a Presidio (fort) at Tubac.

Luis surrendered in 1752. With the safety provided to the Spanish and remaining converted natives, Tubac became the first permanent European settlement in Arizona. While many O’odham returned to the Missions, other Indigenous groups like the Apaches continued fighting against the Spanish colonists. Constant attacks by the nomadic Apaches prevented the growth of Hispanic settlements in the Santa Cruz River Valley during the 1700s. The Apache had been resisting the presence of foreigners for years. As more Spanish settlers established towns in Sonora and along the Santa Cruz River, the Apache resisted by raiding these towns.

Hoping to take control of the Hispanic settlements and the Catholic Church, King Carlos III of Spain expelled the Jesuit priests from the entire Spanish Empire in 1767, including Southern Arizona. As Franciscan priests replaced the Jesuits at the missions, Apache attacks escalated.

The Spanish Empire’s decision to relocate the Tubac Presidio to Tucson in 1775 (the founding of the modern city of Tucson) left the ranchers, miners, and converted Indigenous of what is now Santa Cruz County without protection as Apache power grew. By 1783, they were run off by Apaches, until a unit of the Pima and O’odham soldiers were ordered back to Tubac where they regained control.[4] Many Indigenous People served in the Spanish Army, including some O’odham and Pima men, because of their negative feelings towards the Apaches. From the 1780s-1810s, though, Apaches and the Hispanic colonists reached a truce which ended the years of violence for a time. During this delicate peace, the current-day mission buildings at Tumacácori and San Xavier were built.

A Merging of Cultures

The cultures of both Arizona Spanish settlers and local Indigenous communities changed and influenced each other as they interacted, though much of the Spanish culture was forced onto the Indigenous.

Food was a major site of influence. During ceremonies usually in relation to the church, like weddings, baptisms, and funerals, Spanish guests would eat chocolate and tortillas straying from the customary wheat bread.[5] The settlers’ diets included many Indigenous dishes, like pinole, tamales, and atole, often using maize (corn) as the main ingredient. These common Indigenous foods and ingredients were part of the cultural diffusion. Converted Catholic Indigenous people would also trade eggs and chickens with the Spaniards and missionaries for tobacco and items like knives and needles.

The church was one of, if not the most significant site of cultural influence – and Indigenous colonization. Indigenous children were ordered to recite Christian doctrine every day in both their own language and in Spanish. The Spanish language was ingrained into Indigenous communities through the church and control of the priests. For the baptisms of Indigenous children, Spaniards were sometimes invited or offered themselves to be the godparents.

Hispanic heritage in Southern Arizona is an outcome of both colonization and cultural blending between Jesuit missionaries, Spanish settlers, and Indigenous communities. The Spanish language, which was forced through colonization on Indigenous people, and culturally blended dishes are still central to Southern Arizona’s culture!

The Return of Apache Resistance to Mexican Settlers

When Mexico gained its independence from Spain after its 1810-1821 revolt, Mexican settlers began claiming property through land grants offered by the newly-created state government of Sonora. Mexicans were taking over and distributing Apache and O’odham lands along the Santa Cruz River and surrounding lands.

The era of relative peace between the expanding settler communities – especially in Tubac – came to an end as Mexican military funding declined. Without proper protection, the Apache began raiding and gaining control again in the Southern Arizona Mexican settlements. They reclaimed their lands from the Mexican land grants and drove Mexicans out of Tubac and Tumacácori in the 1840s, with most fleeing south into Sonora.

The situation in the Santa Cruz River Valley was negatively affected by the U.S. invasion of Northern Mexico during the 1846-1848 U.S.-Mexico War. While the U.S. took most of present-day Arizona with the signing of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the Santa Cruz County area remained part of Mexico’s northern Sonora for a few more years. Finally, the U.S. purchased from Mexico the Santa Cruz River Valley and the rest of today’s Southern Arizona and New Mexico in the Gadsden/Mesilla Purchase of 1853-1854.

Santa Cruz County and the Heritage of the 1853-1854 Gadsden/Mesilla Purchase

Armando Moreno (2024), Oil on Canvas

After the establishment of the Gadsden/Mesilla Purchase, Mexican troops began departing from the U.S. territory back to Mexico. By 1856, after completing the transfer of control and escorting the civilians who chose to depart to Mexico, the last of the Mexican soldiers left Arizona via the Santa Cruz River Valley.[7] Before the last soldier stepped out of what would become Santa Cruz County, Americans had already raised the U.S. flag over Tucson and Tubac – symbolizing the end of more than 300 years of Spanish/Mexican colonization. However, as Santa Cruz County’s current 83% Latino majority demonstrates, the Hispanic presence in Southern Arizona would continue growing even after becoming part of the United States.

Conclusion

Missionaries and Spanish settlers used Catholicism as a tool of colonization. They used extreme measures to convert and Hispanicize Indigenous communities. Father Kino played a major role in conversion and colonization. However, native people often resisted the colonizers, especially the Apache who used raiding to re-exert control over their lands. The establishment of presidios was in response to Indigenous resistance, but these Spanish forts never truly gained power and protection over the missions and settlements. Amidst the conflict and interactions of settlers and Indigenous people, their cultures were influencing each other. Their cultures merged from the forced integration of the Spanish language on local Indigenous people to the incorporation of Indigenous dishes into the diets of Spanish settlers.

The Hispanic roots of Santa Cruz Country can be traced back through these interactions. Santa Cruz County is home to Arizona’s largest proportion of Hispanic residents. The Spanish language, Catholicism, and Hispanic foods are still important to the county’s culture and Latino/a identities!

About the Author

Jacey Demaree is an undergraduate student at the University of Arizona, born and raised in Arizona. She is currently a sophomore studying History and Law.

Bibliography

Browne, John Ross. 1869. Adventures in the Apache country: a tour through Arizona and Sonora. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers.

Ehrenberg, Herman. 1853. Map of the Gadsden Purchase Sonora and Portions of New Mexico, Chihuahua & California. State of Arizona Research Library.

Officer, James. 1989. Hispanic Arizona 1536-1856. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Pfefferkorn, Ignaz, and Theodore E. Treutlein. 1989. Sonora: A Description of the Province. University of Arizona Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1g0b98j.

Pradeau, Alberto Francisco. 1974. “Pozole, Atole and Tamales: Corn and Its Uses in the Sonora-Arizona Region.” The Journal of Arizona History 15, no. 1: 1–7. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41695162.

Shea, John Gilmary. 1886. A History of the Catholic Church within the Limits of the United States, from the First Attempted Colonization to the Present Time. New York: J. G. Shea. http://archive.org/details/historyofcatholi02shea.

Truett, Samuel. 2006. Fugitive Landscapes: The Forgotten History of the U. S. -Mexico Borderlands. 1st ed. The Lamar Series in Western History Series. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Venegas, Miguel. 1757. Noticia de la California. Madrid.

[1] Miguel Venegas, Noticia de la California. Madrid, 1757.

[2] John Ross Browne, Adventures in the Apache country: a tour through Arizona and Sonora. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1869.

[3] James Officer, Hispanic Arizona 1536-1856. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1989; 31.

[4] Samuel Truett, Fugitive Landscapes: The Forgotten History of the U.s.-Mexico Borderlands. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006.

[5] Ignaz Pfefferkorn and Theodore E. Treutlein, Sonora: A Description of the Province. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1989.

[6] Herman Ehrenberg, Map of the Gadsden Purchase Sonora and Portions of New Mexico, Chihuahua & California. State of Arizona Research Library, 1853.

[7] James Officer, Hispanic Arizona 1536-1856. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1989; 283.