Armando Moreno (2024), Oil on Canvas

Zachary David Jardee, University of Arizona

Original Photographs by Carlos Francisco Parra

Key Concepts:

- The U.S.-Mexican border’s formation in the area since the 1850s has been a key part of Santa Cruz County’s identity and development

- Over time, the U.S.-Mexico Border in Santa Cruz County has become more built up and militarized in an effort to separate the United States from Mexico.

- Operation Safeguard: U.S. Border Patrol initiative implemented in the 1990s to address increasing undocumented immigration and drug trafficking along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Key Terms:

- Implemented – The act of putting a plan, decision, or system into effect or action.

- U.S.-Mexico Border – A 1,954 mile-long border between Mexico and the United States separating but also bringing the two countries together via migration, trade, and culture.

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo – treaty signed on February 2, 1848, that marked the end of the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) between the United States and Mexico.

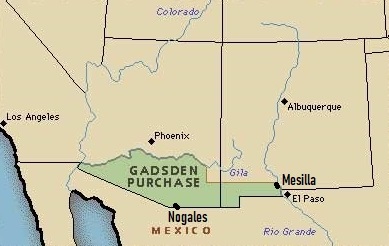

- Gadsden/Mesilla Purchase – was an agreement between the United States and Mexico signed on December 30, 1853, and ratified in 1854. This treaty aimed to resolve a boundary dispute between the two countries and resulted in the United States acquiring a significant portion of present-day southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico.

- Ratified – Indicates the formal approval or confirmation of a treaty, contract, or agreement, making it officially valid.

- bollard-type border wall – a wall consisting of thick posts.

RESEARCH ARTICLE

B3. How has the U.S.-Mexican Border shaped Santa Cruz County? (1848-2024)

Zachary David Jardee, University of Arizona

Original Photographs by Carlos Francisco Parra

Introduction

The year is 1853 and a rancher looking out upon a vast arid desert as far as can see. A harsh sun is beating down on those under it with little shade to be offered and far off in the distance is a settlement. This settlement would come to be known as Nogales, Arizona. A former part of Mexico with no border wall, no fence, no barbed wire, nothing. It was simply a settlement existing within the harsh desert sun near the flowing Santa Cruz River. This river would be the source of the name for Santa Cruz County, and the walnut trees in the surrounding mountains would give Nogales its name.[1]

Now, imagine you are standing at that same spot the rancher stood at back in 1853. It is the present-day. While desert landscapes still surround you, there are now homes, buildings, streets, powerlines, all sorts of modern things. One thing which really stands out is the dark outline of what appears to be a snake going up and down the hills and mountains of Nogales. It is not anything living, but it is real. It’s the U.S.-Mexico border wall, signaling the division between the two nations as well as their profound social and economic differences. Just as Nogales is named after the native walnut trees, Nogales also exists because of the border being marked between the two countries right here starting with the 1853-1854 Gadsden/Mesilla Purchase. In this article we will take a look at why the U.S.-Mexico border was created and some of the ways it has impacted the people of Nogales, Santa Cruz County, and Southern Arizona in the century-and-half since this land was first divided.

Creating the Border with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the Gadsden/Mesilla Purchase

In its first form, the U.S.-Mexican border was far, far away from today’s Santa Cruz County. The original U.S.-Mexican border came into being in 1821 when Mexico won its independence from Spain. The first version of the boundary began at the Pacific Ocean running eastward along ran from the present-day state of Oregon, across to Utah and northern Colorado, and then down along different rivers through Oklahoma and Texas and finally down to the Gulf of Mexico. This border is vastly different from our current-day one and meant that modern U.S. cities like San Francisco, Salt Lake City, and Dallas were all in what was then Mexican territory. Revolts by White American settlers in Texas led to the border shifting as Texas briefly became an independent country before finally joining the U.S. in 1845. Due to a boundary dispute in South Texas, the U.S. and Mexico went to war in April 1846.

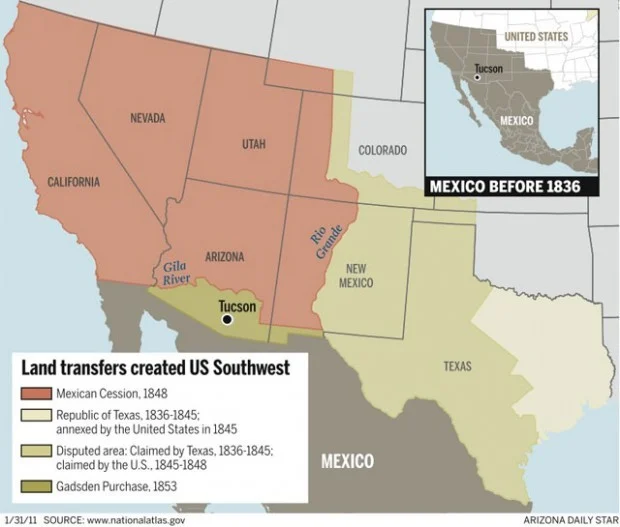

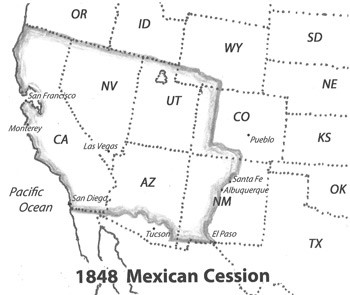

Indeed, the biggest change to the U.S.-Mexican border occurred as a result of the 1846-1848 U.S.-Mexico War in which the U.S. militarily defeated Mexico after invading it from multiple fronts. During this war the U.S. captured Mexico City, forcing the remains of the Mexican Government to accept harsh demands. Specifically, the victorious U.S. sought territorial enlargement as compensation for winning the war. On February 2, 1848, the two nations signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo requiring Mexico to cede the majority of the modern U.S. West to the U.S., ending the war. The vast area Mexico forcibly gave up is known as the Mexican Cession and included all or part of the present-day states of California, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and Arizona – except for the southern corner where Santa Cruz County is located.

Figure 1: Land acquired by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo [2]

Despite the vast amount of Mexican land the U.S. acquired after the war, many U.S. politicians proposed acquiring even more Mexican territory. The main reason for this was that the land the U.S. got in the Mexican Cession did not have an accessible railroad to connect California with the southern slaveholding states. According to several military engineers, the best preferred route was through what is now Southern Arizona and New Mexico. To resolve this, the U.S. sent Ambassador James Gadsden, a slaveholder, to Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna in 1853 to purchase land and settle the remaining issues caused by the recent war.

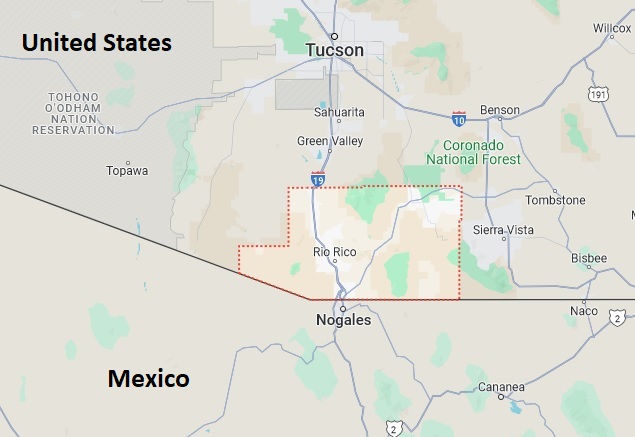

After negotiations the U.S. and Mexico finalized their agreement on June 8th, 1854, in which the U.S. bought 29,670 square miles of land for $10 million. This agreement is known as the 1853-1854 Gadsden or Mesilla Purchase which included modern-day Southern Arizona, including Tucson and all of what is now Santa Cruz County.[3] The Gadsden Purchase can also be called the “Mesilla Purchase” because of its name in Mexico, the “sale of La Mesilla” (Mesilla is the name of a town in New Mexico along the Rio Grande which was included in the Gadsden agreement). The U.S.-Mexican border, including Arizona’s border with the Mexican state of Sonora, took its current shape with the Gadsden/Mesilla Purchase.

Figure 2: The U.S. acquired what is now Santa Cruz County and the rest of Southern Arizona and New Mexico in the 1853-1854 Gadsden/Mesilla Purchase [4]. In Mexico this land deal is called the Mesilla Purchase/Sale of La Mesilla in honor of the largest town included in the agreement, Mesilla, New Mexico (right). SOURCE: National Park Service (https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/new-mexico-mesilla-plaza-and-mesilla-historic-district.htm).

The Heritage of the 1853-1854 Gadsden/Mesilla Purchase

Armando Moreno (2024), Oil on Canvas

Boundary Monuments

Before the U.S.-Mexico border finished taking shape with the Gadsden/Mesilla Purchase, both governments began surveying (mapping) the border. Starting on December 4th, 1849, the U.S. Boundary Commission began placing boundary monuments, the first form of marking between the two nations that denoted what land belonged to each. Initially, these monuments were just piles of rock and would soon transform into columns of stone with iron. It took nearly ten years to mark the border due to the challenges of surveying long distances in the desert.

In late spring 1855, the U.S. survey group arrived ahead of the Mexican survey team in what is now the Nogales area to mark the border. Working alone, the U.S. surveyors marked incorrect boundaries for the Gadsden/Mesilla Purchase border. Specifically, the point where the international boundary follows an angle between the Mexican state of Sonora and what is now the U.S. state of Arizona. This boundary angle was created to allow Mexico to keep a land connection to the Baja California peninsula via northwestern Sonora.

The U.S. team placed the boundary angle 4.41 miles too far west, giving the U.S. more Mexican land that it was supposed to have, according to the Gadsden/Mesilla Purchase agreement. The Mexican survey party led by Captain Francisco Jiménez, arrived late due to political unrest in Mexico and took the U.S. survey party led by Major William Emory for their word. What is now numbered Boundary Monument 127 still marks this distinctive, but incorrectly-surveyed section of the U.S.-Mexican border between Nogales and Yuma, Arizona. [6]

Figure 4: In the Pajarito Mountains west of Nogales, Boundary Monument 127 marks the distinctive boundary angle between Arizona, U.S.A. and the Mexican state of Sonora. Photo by Carlos F. Parra. [7]

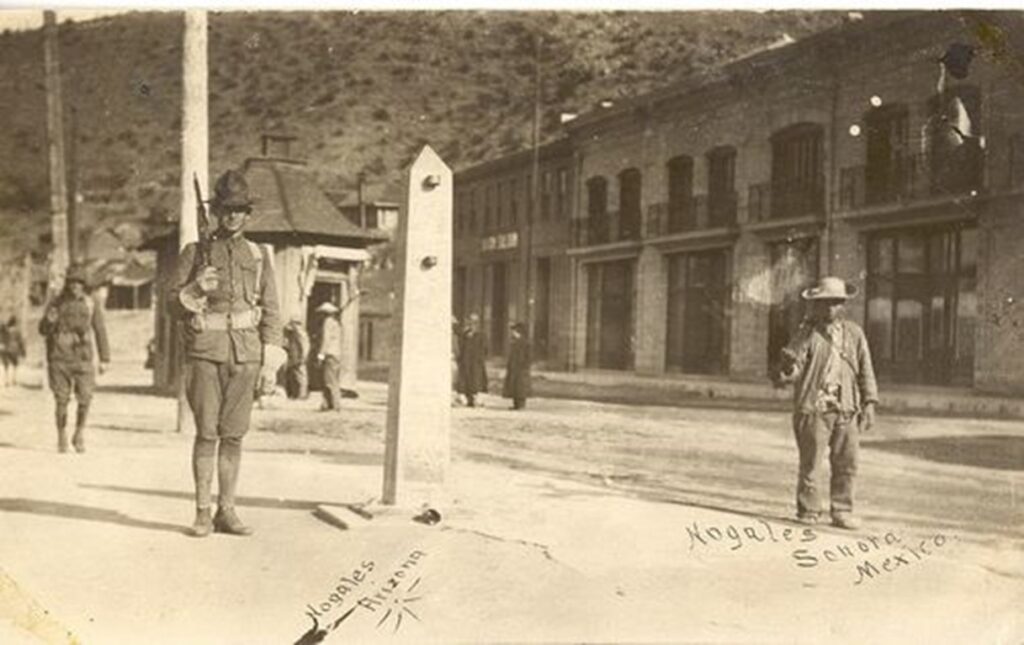

The U.S. and Mexico resurveyed the border in the 1890s and assigned new numbers to the cast iron monuments they installed to mark the border. Boundary Monument 122, one these 1890s-era structures, still stands today and is an iconic and historical landmark between the two Nogales which has appeared in many books and articles.

Figure 3: Boundary Monument 122 splitting Nogales, Arizona (left) from Nogales, Sonora, Mexico (right) in the 1910s (above) and in 2024 (below). Note the changes in the border’s appearance in the 110 years between the two photographs, especially the border wall to the left and the Mexican port of entry building in the background constructed between 2023-2024. Bottom image by Carlos F. Parra. [5]

Boundary Monument 122 as seen in 2024 on the Mexican side of the Calle Elías/Morley Avenue Port of Entry. Photo by Carlos F. Parra.

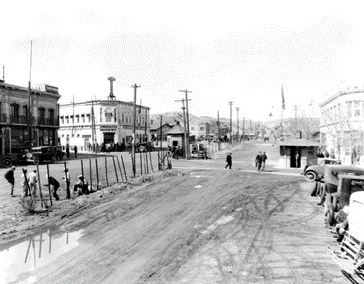

Arizona’s Main Port of Entry with Mexico

Decades later the city of Nogales was founded right along the center of Arizona’s border with Sonora as the first railroad linking Mexico and the U.S. was being built. In time Nogales became the primary port of entry from Mexico to the U.S. as well as a place facilitating trade and cultural exchange. In 1882, the construction of the railroad across the border made Nogales a transportation hub between the U.S. and Mexico as well as the first cross border railroad between the two countries.[8] From 1910-1920 the Mexican Revolution (a violent civil war in Mexico) caused an influx of migrants and refugees to the Nogales border. This influx would help to solidify Ambos (or both) Nogales as the main port of entry between Mexico and the U.S. for both people and goods. Ambos Nogales grew into a bustling center of commerce.[9]

Development of Fences/Walls on the Border

Today, Nogales is strongly associated with border fences and walls, but before 1918 there was nothing dividing the U.S.-Mexico border between Ambos Nogales. One could simply walk across the imaginary border line on International Street to enter the other country. However, that changed due to distrust and fears which emerged between both countries during the Mexican Revolution and World War I. During the 1910s, many mexicanos were shot by U.S. border guards because they crossed the imaginary line too far from the border inspectors. Repeated instances of this led to the violent August 27, 1918 Battle of Ambos Nogales in which the U.S. Army and Mexican civilians in Nogales, Sonora, fought against one another. As a result, both countries agreed to build fences to prevent more shootings by having people cross as designated points where they could be inspected. By the 1920’s fences became the norm separating the two nations at border towns. But those fences were not yet militarized nor were they called walls.[10]

Figure 5: Border fence in Nogales 1929[11]

On May 28, 1924, the United States established the U.S. Border Patrol to secure and patrol the border.[12] A few years later, the U.S. joined World War II (1941-1945), during which both the U.S. and Mexican economies experienced staggering growth. With the U.S. needing more workers during the war, the Bracero Program was created, enabling Mexicans to cross the border and work on U.S. farms. This program ran from 1942 to 1964 and led to growth in both technological advancements and manufacturing for both countries.[13]

While in many ways the U.S. and Mexico came closer, longstanding distrust between the two countries remained. For example, Presidents Richard Nixon (1969-1974) and Ronald Reagan (1981-1989) launched numerous policies to control the border. Nixon launched the “war on drugs” to stop drug trafficking, often causing long delays for ordinary people waiting in line to cross the border by car. Reagan increased immigration enforcement to try to control the flow of migrants.[14]

As time progressed to the 1990’s the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) set an initiative to secure control of the southwest border with Mexico. This initiative would come to be known as Operation Safeguard; a massive operation taken on by the U.S. Border Patrol. In 1999, Nogales would implement Operation Safeguard with U.S. Border Patrol to gain control of the border and limit the number of illegal crossings. It was a tactic of deterrence through force, as the Border Patrol in Nogales was bolstered with many new agents and the construction of more border fences. This forced potential undocumented migrants to take more dangerous routes entering the United States through the desert west of Nogales.

During the 1990s, the U.S. Government installed new layers of border fencing in the Nogales area. The 1990s-era fences (which were still not called walls) were in fact unused steel airplane landing mats left over from the Vietnam War. Green and brown-colored, the fences snaked along the hills of Nogales and had barbed wire on top. The fences only went a few miles in each direction from downtown Nogales and were often cut by smugglers using blow torches. Artists in Mexico would often paint murals on the border fence or put art installations on it. In 2011 the corrugated steel fences were replaced with a bollard-type border wall (a wall consisting of thick posts) which still divides Ambos Nogales as of 2024. Although built under President Barack Obama, this see-through bollard border wall would become the basis of the border wall project promoted by President Donald Trump in 2019-2021.

The U.S.-Mexico border witnessed a significant escalation in militarization during both the Obama and Trump administrations. Under Obama, the approach emphasized a mix of increased border security measures, including the deployment of additional Border Patrol agents and technological surveillance systems. However, it also saw a push for immigration reform, with efforts to address the status of undocumented immigrants already within the United States.[15] In contrast, the Trump administration pursued a more aggressive stance, advocating for the construction of a border wall as a central component of its immigration policy. This rhetoric fueled tensions and resulted in heightened militarization, with the deployment of National Guard troops, further expansion of border barriers, and utilization of barbed and razor wire. Additionally, policies such as “zero tolerance” led to the separation of families and sparked widespread controversy and condemnation.[16] The militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border remains a contentious issue, reflecting broader debates over immigration, security, and humanitarian concerns.

Covid-19 and the Border

During the 2020-2021 COVID-19 pandemic, Nogales, Arizona experienced severe hardship especially surrounding the border. The City of Nogales, following the federal government’s guidelines implemented stringent public health measures to curb the spread of the virus including mask mandates, social distancing guidelines, and restrictions on gatherings. However, the most significant aspect of the coronavirus pandemic related to the international boundary was the border’s closure for 20 months. As the virus outbreak continued to grow, the U.S. Government closed the border to non-essential traffic from March 2020 to November 2021.[17]

While large-scale industrial trade continued, smaller merchants in Nogales, Arizona, depending on Mexican day-tourists and shoppers suffered greatly. This led to job losses, business closures, and disruptions to the local economy, particularly in areas such as tourism and retail. Many local businesses closed due to border closures, leaving owners without their usual cross-border customers, resulting in a lack of sales. Compounded by border restrictions and travel limitations due to Nogales’ proximity to Mexico, the community navigated a complex landscape of challenges during this unprecedented time. Many of the stores which went out of business during the border’s closure remain vacant today.

Conclusion

Today, the border of Nogales, Arizona is more than just a static line on a map; it’s a dynamic narrative shaped by history and societal forces. From its origins as an imaginary boundary to its current state as a militarized divide, the border reflects the ever-changing nature of its surroundings. Despite the physical barrier, the communities of Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora, adapt and collaborate, demonstrating resilience in the face of challenges. As time progresses, the border will continue to evolve, but the enduring spirit of Nogales ensures that local folks will persevere, tackling new issues with unity and determination, standing as a testament to the strength of communities bound by shared history and struggles. The scenes in Nogales today are very different from those a rancher would have seen in 1853, but they are reminders of the constant change along the U.S.-Mexican border.

About the Author

Zachary Jardee is an Arizona local in the Tucson area attending the University of Arizona as an undergraduate student. He is currently a senior studying History with a minor in Education.

Bibliography

“A Brief Legislative History of the Last 50 Years on the U.S.-Mexico Border.” A Brief Legislative History of the Last 50 Years on the U.S.-Mexico Border | Mexico Initiatives, April 28, 2020. https://mexico.arizona.edu/revista/brief-legislative-history-last-50-years-us-mexico-border.

“Continuing to Strengthen Border Security.” The White House President Barack Obama. Accessed May 8, 2024. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/issues/immigration/border-security.

“February 2, 1848 – Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.” Legal Legacy, January 10, 2020. https://legallegacy.wordpress.com/2015/02/02/february-2-1848-treaty-of-guadalupe-hidalgo/.

“Gadsden Purchase, 1853–1854.” U.S. Department of State. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1830-1860/gadsden-purchase.

Ganster, Paul, and Kimberly Collins. “Boom and Busts on the Border The Great Depression and World War II.” Essay. In The U.S.-Mexican Border Today : Conflict and Cooperation in Historical Perspective, Fourthed., 85–101. Latin American Silhouettes. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2021.

“History – City of Nogales.” History – City of Nogales, 2023. https://nogalesaz.gov/economic-development/history/.

“Immigration.” Trump White House. Accessed May 8, 2024. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/issues/immigration/.

John, Rachel St. “The Raging Controversy at the Border Began with This Incident 100 Years Ago.” Smithsonian.com, July 1, 2018. https://smithsonianmag.com/history/raging-controversy-border-began-100-years-ago-180969343/.

Miller, Michael E. “Pancho Villa, Prostitutes and Spies: The U.S.-Mexico Border Wall’s Wild Origins.” The Washington Post, January 10, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/01/10/pancho-villa-prostitutes-spies-us-mexico-border-walls-wild-origins/.

Parra, Carlos Francisco. “The August 27, 1918 Battle of Ambos Nogales and the First US-Mexico Border Fences Part 1.” NOMADIC BORDER | LA FRONTERA NOMADA, November 20, 2017. http://www.nomadicborder.com/battle-of-ambos-nogales-part-1.html.

Parra, Carlos Francisco. “Monumental Border Mistake: Boundary Monument 127 and the Arizona-Sonora Border.” NOMADIC BORDER | LA FRONTERA NOMADA, January 20, 2021. http://www.nomadicborder.com/monumental-border-mistakes-boundary-monument-127.html.

Serrano, Christian. “Reopening of Border after 20 Months Is Both Exciting and Low Key in Nogales.” Cronkite News, November 8, 2021. https://cronkitenews.azpbs.org/2021/11/08/reopening-of-border-after-20-months-is-both-exciting-and-low-key-in-nogales/.

“The Gadsden Purchase.” ¡Viva Mesilla! Accessed May 8, 2024. https://www.oldmesilla.org/html/gadsden_purchase.html.

“Train Crossings.” Arizona. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://azmex.eller.arizona.edu/border-crossings/train-crossings.

Zeidan, Adam. “Invasion and War.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Accessed May 5, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/event/Mexican-American-War/Invasion-and-war.

“1924: Border Patrol Established.” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, August 3, 2023. https://www.cbp.gov/about/history/1924-border-patrol-established.

Notes

[1] “History – City of Nogales,” History – City of Nogales, 2023, https://nogalesaz.gov/economic-development/history/.

[2] “February 2, 1848 – Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo,” Legal Legacy, January 10, 2020, https://legallegacy.wordpress.com/2015/02/02/february-2-1848-treaty-of-guadalupe-hidalgo/.

[3] “Gadsden Purchase, 1853–1854,” U.S. Department of State, accessed May 5, 2024, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1830-1860/gadsden-purchase.

[4] “The Gadsden Purchase,” ¡Viva Mesilla!, accessed May 8, 2024, https://www.oldmesilla.org/html/gadsden_purchase.html.

[5] Carlos Francisco Parra, “The August 27, 1918 Battle of Ambos Nogales and the First US-Mexico Border Fences Part 1,” NOMADIC BORDER | LA FRONTERA NOMADA, November 20, 2017, http://www.nomadicborder.com/battle-of-ambos-nogales-part-1.html.

[6] Carlos Francisco Parra, “Monumental Border Mistake: Boundary Monument 127 and the Arizona-Sonora Border,” NOMADIC BORDER | LA FRONTERA NOMADA, January 20, 2021, http://www.nomadicborder.com/monumental-border-mistakes-boundary-monument-127.html.

[7] Carlos Francisco Parra, “Monumental Border Mistake: Boundary Monument 127 and the Arizona-Sonora Border,” NOMADIC BORDER | LA FRONTERA NOMADA, January 20, 2021, http://www.nomadicborder.com/monumental-border-mistakes-boundary-monument-127.html.

[8] “Train Crossings,” Economic and Business Research Center, accessed May 5, 2024, https://azmex.eller.arizona.edu/border-crossings/train-crossings.

[9] Vera Pavlakovich-Kochi, “Assessing Nogales, Arizona’s Major Border Port of Entry,” Arizona’s Economy, December 3, 2018, https://www.azeconomy.org/2018/12/border-economy/assessing-nogales-major-border-port-of-entry-for-arizona/.

[10] Rachel St. John, “The Raging Controversy at the Border Began with This Incident 100 Years Ago,” Smithsonian.com, July 1, 2018, https://smithsonianmag.com/history/raging-controversy-border-began-100-years-ago-180969343/.

[11] Michael E. Miller, “Pancho Villa, Prostitutes and Spies: The U.S.-Mexico Border Wall’s Wild Origins,” The Washington Post, January 10, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/01/10/pancho-villa-prostitutes-spies-us-mexico-border-walls-wild-origins/.

[12] “1924: Border Patrol Established,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, August 3, 2023, https://www.cbp.gov/about/history/1924-border-patrol-established.

[13] Paul Ganster and Kimberly Collins, “Boom and Busts on the Border The Great Depression and World War II,” essay, in The U.S.-Mexican Border Today : Conflict and Cooperation in Historical Perspective, Fourth, Latin American Silhouettes (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2021), 85–101.

[14] “A Brief Legislative History of the Last 50 Years on the U.S.-Mexico Border,” A Brief Legislative History of the Last 50 Years on the U.S.-Mexico Border | Mexico Initiatives, April 28, 2020, https://mexico.arizona.edu/revista/brief-legislative-history-last-50-years-us-mexico-border.

[15] “Continuing to Strengthen Border Security,” The White House President Barack Obama, accessed May 8, 2024, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/issues/immigration/border-security.

[16] “Immigration,” Trump White House, accessed May 8, 2024, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/issues/immigration/.

[17] Christian Serrano, “Reopening of Border after 20 Months Is Both Exciting and Low Key in Nogales,” Cronkite News, November 8, 2021, https://cronkitenews.azpbs.org/2021/11/08/reopening-of-border-after-20-months-is-both-exciting-and-low-key-in-nogales/.