Tristan M. Storrs, University of Arizona

Key Concepts:

- Conflict with Nde people: Conflict with the Apache (Nde) was common for much of calabazas’ history.

- Bascom Affair – A confrontation between US army/settlers and Apache (Nde) tribe around Calabasas, Arizona, which started the Apache Wars, that lasted for around 20 years. The affair was named after Second Lieutenant George Bascom, who was the commander of US forces in the region.

- Change in human settlements in Calabazas and along the Santa Cruz River Valley: from O’odham & Apache (Nde) to Spanish & American, who were those settlers, and why were they coming here?

Key Terms:

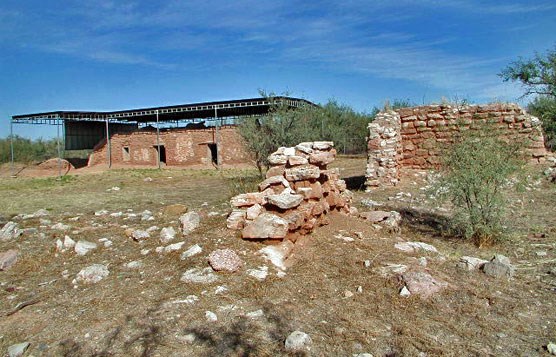

- Calabazas/Calabasas: The region has two different spellings. The original spelling is “Calabazas” which means “pumpkin” in Spanish, the Spanish gave the region that name for the desert gourds that grew in the area. “Calabasas” is an Americanization of the original name. Both terms will be used to refer to different periods of the region’s history, or different locations of settlement; as shown on the map on page 5, Calabazas, and Calabasas are separated by Sonoita Creek.

- Mission San Cayetano de Calabazas: a Spanish mission settled by O’odham people in 1756 and was abandoned for its original purpose in 1786.

- Settlers: People who settle in a country or region, where they were not born, and are foreign.

- Mission: Spanish Churches that were constructed to both convert and exercise control over native populations.

- Ghost Town: the remnants of a town that failed or was abandoned.

- Land grant: A formal act of a government giving ownership of a defined area of land to a person or corporation.

- Custom House: A place where duties or customs are collected from foreign trade. Duties/customs are a form of tax, that are applied to goods that are imported from another country

- “The Line”: a phrase that refers to the U.S. Mexican border.

B6 Special Focus: The Lost Border Town of Calabazas/Calabasas

Tristan M. Storrs, University of Arizona

Introduction

Ghost towns have often captured people’s imagination, and Arizona is full of them. People like to imagine the past lives of those who lived in the “Wild West” and to peer back into life from a different time, without the modern conveniences we enjoy today. Calabasas, or Calabazas as the Spanish called it, is one of these ghost towns, except it rarely captures the publics attention, because barely any of it exists today save for the remains of its oldest standing structure, San Cayetano de Calabazas, an old Spanish mission and a cemetery. The former town, sits on the site that is now Rio Rico, a 1970s suburb, but what caused Calabasas to be abandoned?

The site has been abandoned or fallen out of use several times since Tohono O’odham people first settled there. The site’s history as a permanent settlement goes all the way back to the original mission established in the region. Settlements here often failed because southern Arizona before the 1900s was an unpredictable place, that was constantly in a state of flux and change. That change frustrated settlement and development. Calabazas serves as a great example of the fact that nothing is permanent in Southern Arizona.

Before Calabazas

Located where Sonita Creek feeds into the Santa Cruz River, this region was populated by agricultural peoples, known today as the Tohono O’odham, but then simply as “the people” or O’odham. The region, despite being in a desert, was at the time lusher and more fertile than it is today. This was due to the Santa Cruz River and Sonoita Creek, which at the time flowed year-round. This made the region great for agriculture, as Spanish and then later American settlers were able to grow corn here without any irrigation, which is usually required in desert climates (Francis & Valentine, 1878).

The O’odham were not the only people in this region though. The Apache, known to themselves as the Nde, meaning “the people” were also in the region. The Nde were known for being highly nomadic and had somewhat of a bad reputation with the more settled tribes. For example, the Nde often raided the settlements of other tribes, like the O’odham when they could not get the resources they needed on their own (“Native Peoples of the Sonoran Desert: The Nde (U.S. National Park Service),” n.d.). The Nde would often ride along Sonoita Creek down from their mountain settlements in the east to raid O’odham and Hispanic settlements along the Santa Cruz River. This made the rivers of great importance to both peoples as they used them as war paths or to irrigate crops (Ready, 1976).

A Spanish Mission

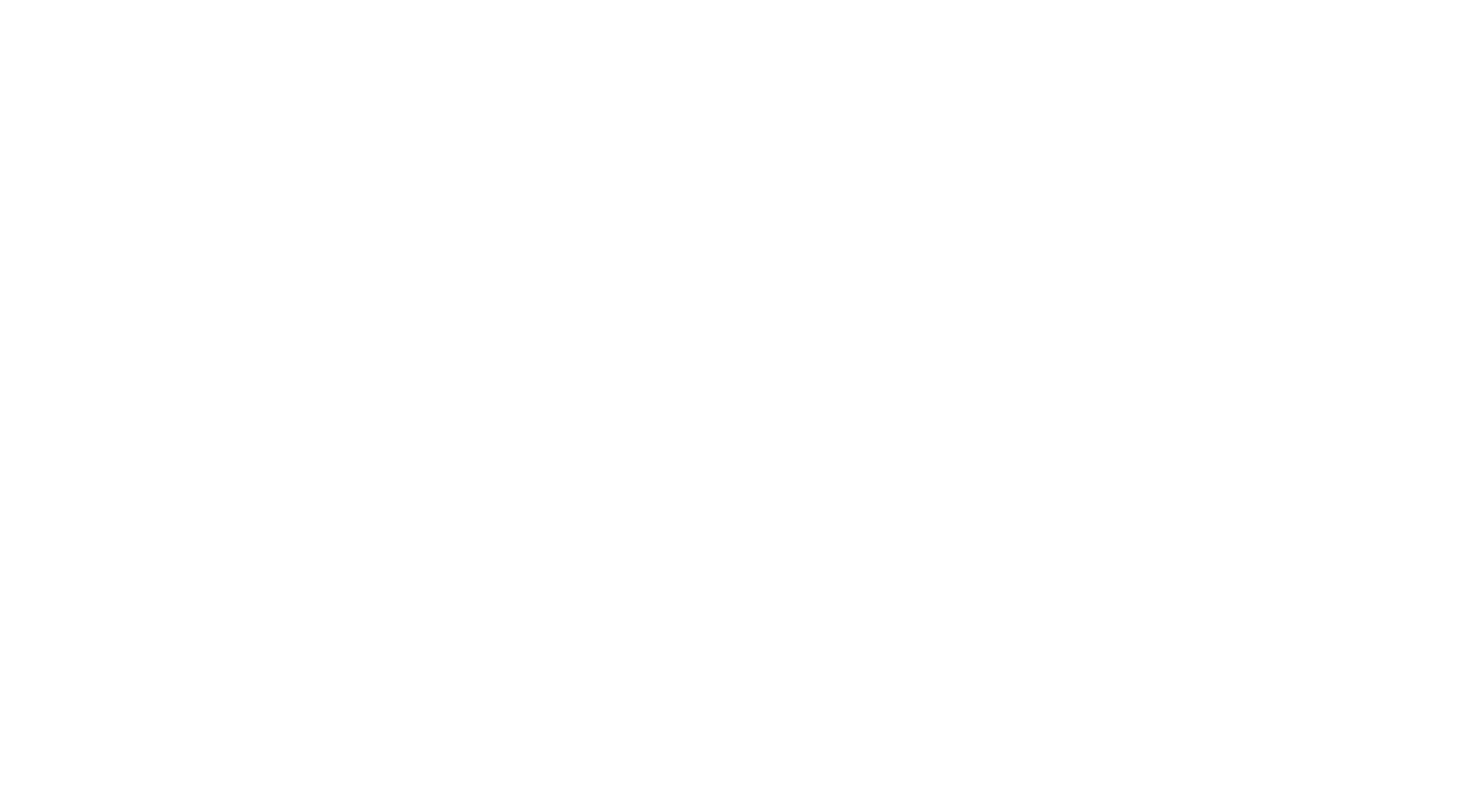

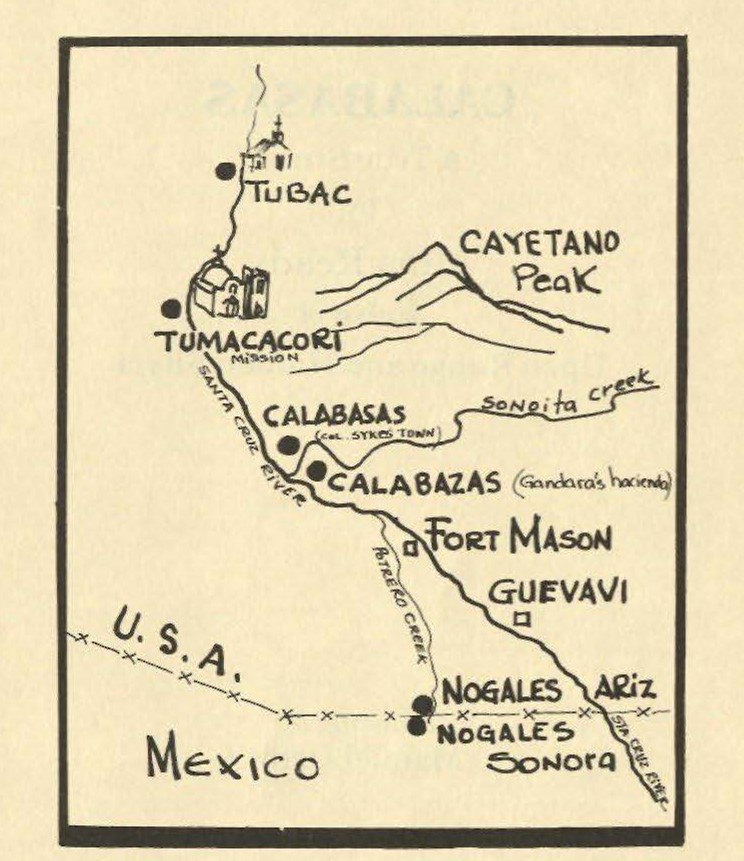

Mission San Cayetano de Calabazas was founded in 1756 by Father Francisco Xavier Pauer and around 80 O’odham. This was one of three Spanish missions founded along the Santa Cruz River and which comprised the larger extent of Spanish settlement in the region. The goal of these missions was to establish Spanish presence in the area, as well as to spread Catholicism to the native peoples of Southern Arizona. The mission at Calabazas did not last long though, as it was frequently the subject of Nde raids. These raids made the mission system unsustainable; throughout the 1780s the missions were consolidated, with Mission San Cayetano de Calabazas being abandoned by the Spanish in 1786 (Ready, 1976). Homes and produce warehouses surround the ruins of Mission San Cayetano de Calabazas. The San Cayetano Mountains towering over Rio Rico’s east side are named after the former mission.

(Ready, 1976)

A Home for Cattle

Calabazas would not stay abandoned for long. In 1806, Juanico Legarra, the native governor of the O’odham people at Tumacácori, successfully petitioned the Spanish government for a land grant in Calabazas. The region was used by the O’odham primarily for cattle grazing and agriculture. It would continue to be a site for cattle grazing potentially into the 1840’s but the history of the region is murky through this period, as Spanish priests were forced out of the area after Mexico gained independence in 1821. These priests had served as the main record keepers about Spanish and native activity in the area, making definitive dates hard to establish. They were forced to leave by the new Mexican government, who wanted to remove the influence of Spanish born Missionaries from Mexico.

Amid the turmoil of Mexico’s first years of independence, the Santa Cruz River Valley became greatly destabilized as the Nde began to intensify their raiding of settlements in southern Arizona. This caused to Hispanic settlers to flee south and made conditions more precarious for the O’odham people. Eventually this situation would be stabilized, after Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, the dictator of Mexico, directed the abandoned lands of Mission Calabazas to be sold. The former mission was eventually purchased by the governor of Sonora, Manuel Maria Gandara. Gandara would use the land for cattle grazing until the Gadsden Purchase in 1854. He was never able to put the land to full use though, as Nde raiding parties continued to attack the cattle and settlers in the region. Once the Gadsden Purchase was made, transferring the land to the United States; Mexican troops left the region. This led to the area being temporarily abandoned once more, as settlers left due to a lack of military protection.

People would flock back to the Calabazas region, after the establishment of Camp Moore in 1856. Camp Moore is located where Fort Mason is marked on the map, which itself is the site of an even older Spanish Presidio or fort. The presence of US troops in the region gave way to a new wave of human settlement (Fontana 1971). The constant changes during the first half of the 1800s made permanent settlement in the region all but impossible. It went through three major political changes, from being a part of Spain, Mexico, and then finally the United States. Each change produced instability, and flare-ups in tensions between settlers, the O’ Odham, and the Nde. This allowed for Nde influence over the region to flourish but frustrated the efforts of the more settled O’odham and the Spanish & American settlers who were new to the region.

The Bascom Affair & The Civil War

The Bascom affair was the inciting event of the Apache (Nde) Wars between the US government and the Nde People. The war started in January 1861 and lasted until 1886. The inciting affair was named after George Bascom, a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army. The inciting event was the kidnapping of a young boy from a ranch along Sonoita Creek, during a raid by the Nde. The US Army responded by taking 6 Nde people of the Chiricahuas tribe hostage, who they wrongly believed to have been involved in the raid. Bascom, wanted to use these hostages as leverage in hostage negotiations, but neither side was able to successfully negotiate a conclusion to the incident. This was in part due to Bascom repeatedly betraying the trust of the Nde, this led to a two-month escalation of conflict that resulted in the death of the 6 Chiricahuas, and over 150 Americans.

After the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War, US troops left Camp Moore leaving the settlers in Calabazas defenseless against Nde raids. This would lead to many settlers fleeing the area, with only well-established towns like Tucson and a few mining settlements holding out during this period. After the end of the Civil War, troops were sent back to Camp Moore in 1865. The forced garrisoned there renamed the site “Fort Mason” and their job was to secure the border during the 1860s French invasion of Mexico. An epidemic in 1866, would cause the abandonment of Fort Mason, with U.S. troops restationing themselves around Tubac. The pressures on the region caused by Nde raids of settlers, was significantly alleviated by 1875, as by that point, the U.S. army had managed to force most of the Western Nde onto reservations, effectively pacifying them. This subjugation of the Nde would provide the region a new level of stability, that enabled the potential for growth and ended a period of instability that was marked by constant conflict and troop withdrawals due to war & disease (“UNITED STATES MILITARY POSTS on the MEXICO BORDER (1856 to PRESENT),” n.d.).

Sykes and the Town of Calabasas

The town of Calabasas was located 2 miles north of the old mission, San Cayetano de Calabazas. It was founded by Colonel Charles Sykes, a businessman from New York in 1877, after he purchased the land from former Sonoran Governor Manuel Gandara. Despite the ongoing conflicts with the Nde, Sykes envisioned Calabasas as a metropolis for cross border trade and the collection of customs (Ready, 1976). Sykes built the Santa Rita Hotel and laid out an ambitious plan for his new city, plotting out a large street grid for future growth. This optimism was based on the site’s prime location between the bustling town of Tucson and the U.S. border with Mexico. During this same period, a railroad was under construction by a company of which Sykes was a partial owner. This railroad enabled the more efficient movement of passengers and freight between Mexico and Tucson. It did not take a direct route though, instead it ran along Sonoita Creek through Patagonia to Benson and then finally to Tucson. Later a more direct route would be built along the Santa Cruz River; this route still serves as the primary rail corridor today.

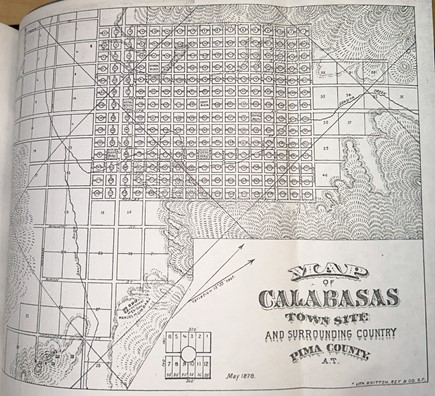

Sykes’s proposed layout for Calabasas. Note how what is now Rio Rico was still part of Pima County in the late 1870s – Santa Cruz County would not be created until 1899. (Lith. Britton, Rey & Co 1879)

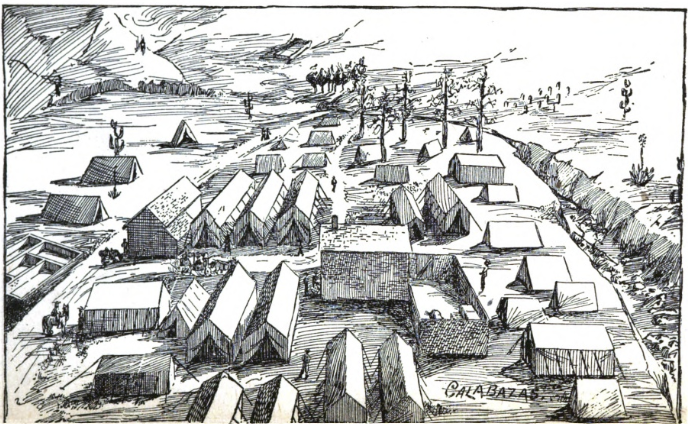

The old Mission was repurposed into a U.S. Customs House, for goods imported from Mexico. At that time, Nogales did not yet exist, which is why a U.S. Customs House was built in Calabasas to tax international trade. A tent city was erected around the customs house, catering to the gambling and drinking habits of the residents and railroaders. Most of the less respectable activities, commonly associated with the “Wild West” supposedly took place in this tent city.

The Calabasas tent city in the late 1870s-early 1880s. (Brown 1892)

Procurement: Catalog Record: Calabazas : or, amusing recollections of an… | HathiTrust Digital Library

This tent city in Calabasas was referred to as “Hell’s Hollow” according to historian Alma Ready (Ready, 1976). A former resident of this tent city, J. Cabell Brown in his 1892 book Calabazas: or Amusing Recollections of an Arizona ‘city’, described it as a place full of men that were “characteristic ones of the far West.” (Brown 1892, 23). He also said, “they would express unbounded affection for each other one moment, and then the next, in a quarrel over some trivial matter, use one another for targets.” (Brown 1892, 23). Brown described the residents of Calabazas as being quick to shoot, but that they would mourn the people they inevitably shot. In one instance, he describes two friends fatally shooting each other, because one corrected the others grammar. He quipped, “that to be grammatical, in Calabazas, was to covet death” (Brown 1892, 23). The Calabasas that Brown described was a hard town, that hardly seemed to be a town at all, instead merely a collection of tents full of quick shooting gamblers and drinkers. The demeaner of Calabasas’ residents might best be explained by their reasoning for living there, which Brown attributed to be very different from what Sykes had envisioned. According to Brown it was not a metropolis for trade, but rather a convenient spot for those with long criminal records to flee to Mexico across “the line” when the law came looking for them.

The Demise of the Town of Calabasas

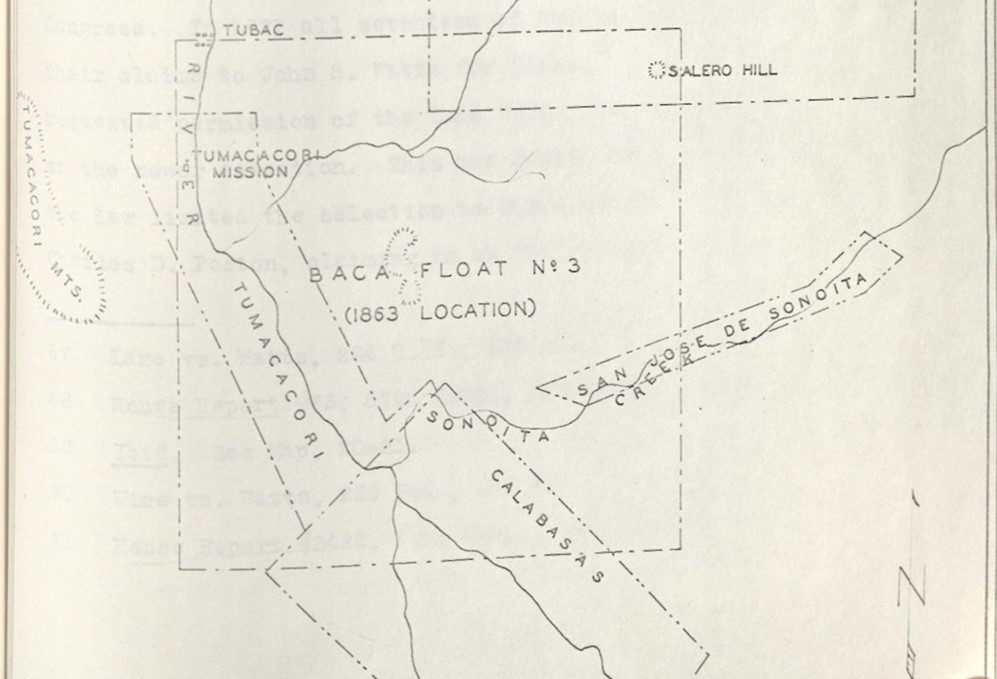

Ultimately, Sykes’ grand plans for Calabasas to be a metropolis of trade never materialized. He was only ever able to build a hotel and a county store when the U.S. Customs House was moved to the newly established town of Nogales, known then as “Isaacson town”. The loss of the Customs House was a major blow to Sykes’ vision for the town and interest in it would start to wane. An anti-Chinese riot in the town, caused the inhabitants of the tent city to move to Nogales, leaving the town effectively dead (Brown 1892). After these departures all that remained was the Santa Rita Hotel, which closed and became the private residence of the Sykes Family. Sykes himself would later be forced off his land, after a private land claims court, set up by the U.S. government to determine the legitimacy of land grants purchased from former Mexican landowners, ruled that the sale from Gandara to Sykes had been illegal. According to the court, Calabasas was actually part of a property called Baca Float #3.

The U.S. Government created “Baca Float #3” over the Calabasas townsite, forcing Sykes and other property owners to abandon the community as it became a single piece of private property. (Mattison, Ray H 1965)

After a prolonged legal battle, Sykes and 51 other claimants were forced off their lands, so that it could be returned to public ownership and management. This did not occur, however, as the government transferred the land to representatives of the prominent Baca Family. The land given to this family representative was designated as Baca Float #3, as compensation for land elsewhere that had been legally granted to the family by Mexico, but was later stolen (Mattison, Ray H 1965). The Baca Float #3 business group did not share Sykes’ dreams to make Calabasas a metropolis. The Santa Rita Hotel would be used as a hay barn until it eventually burned down, leaving the Mission church and the nearby town cemetery as the sole remaining structure in Calabazas/Calabasas. The Mission would fall into ruin, being preserved only recently in the 1960s, when it gained status as a National Historic Site. This final period of human settlement before the modern-day suburbs of Rio Rico was doomed by political instability. First Calabasas lost its prominence due to the founding of Nogales, which stole its trade and citizens and then Sykes lost the land in a court case.

In many ways Rio Rico’s emergence in the 1960s as a residential development is a weird echo of Sykes’s vision for the region. Calabasas became a planned community after all, not a metropolis but a suburb and extension of the growing city of Nogales. Rio Rico is just one of the many changes that have happened in the region and is a product of the flux and change that occurred before its establishment. Interest drifted away from Calabasas for a while, but then it came back again with the foundation of Rio Rico. The developers of Rio Rico had for the first-time stability, allowing for development that in the past was doomed by instability.

Bibliography

“Map of the Santa Cruz Valley Region, Arizona Territory, Including Calabasas, Tubac, San Xavier Mines, Tucson & Santa Rita Mts.” San Francisco, Calif.: San Francisco Lith. Britton, Rey & Co, 1879.

“Native Peoples of the Sonoran Desert: The Nde (U.S. National Park Service).” n.d. Www.nps.gov. https://www.nps.gov/articles/apache.htm.

Prospectus and Reports of the Property of the Calabasas Land and Mining Co. Located in Pima County, Arizona Territory. San Francisco: Francis & Valentine, 1878.

“UNITED STATES MILITARY POSTS on the MEXICO BORDER (1856 to PRESENT).” n.d. https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/pdf/scvnha/chapter04_j.pdf.

Brown, James Cabell. 1892. Calabazas: Or, Amusing Recollections of an Arizona “City. Hathi Trust. San Francisco: Valleau & Peterson. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008961303.

Fontana, Bernard . 1971. “Calabazas of the Rio Rico.” The Smoke Signal 24.

Mattison, Ray H. The Controversy in Southern Arizona over the Tumacacori and Calabasas Land Grants. s.l.: s.n., 1965.

Ready, Alma. Calabasas : a True Story. Nogales, Ariz.: Alto Press, 1976.