Steve Gastellum, Retired National Park Ranger

Key Concepts

- Oral histories with family members and community elders are an important way of understanding the past and ourselves

- Family oral history interviews/conversations helped author Steve Gastellum research the history of the Baca Float #3 land grant which led to 200 homesteading/ranching families in Santa Cruz County losing their homes in the 1910s

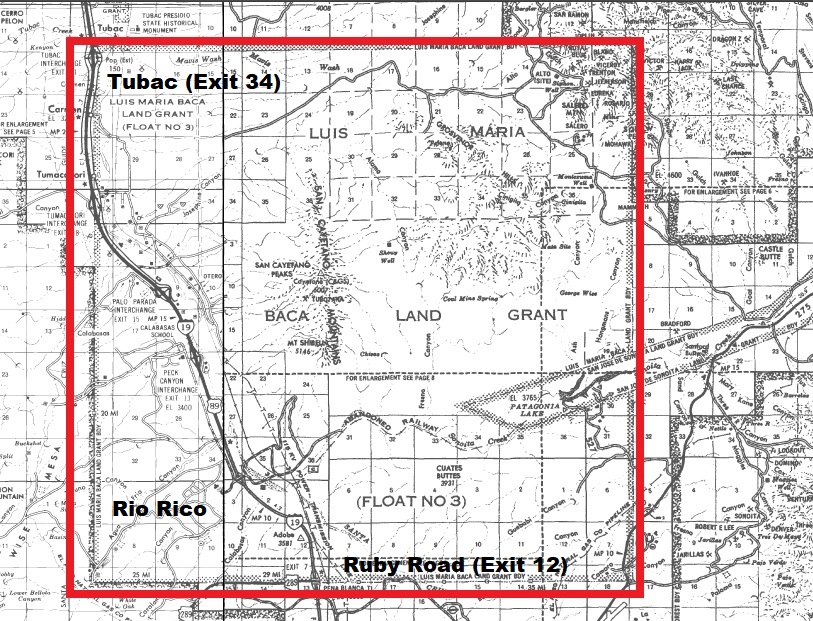

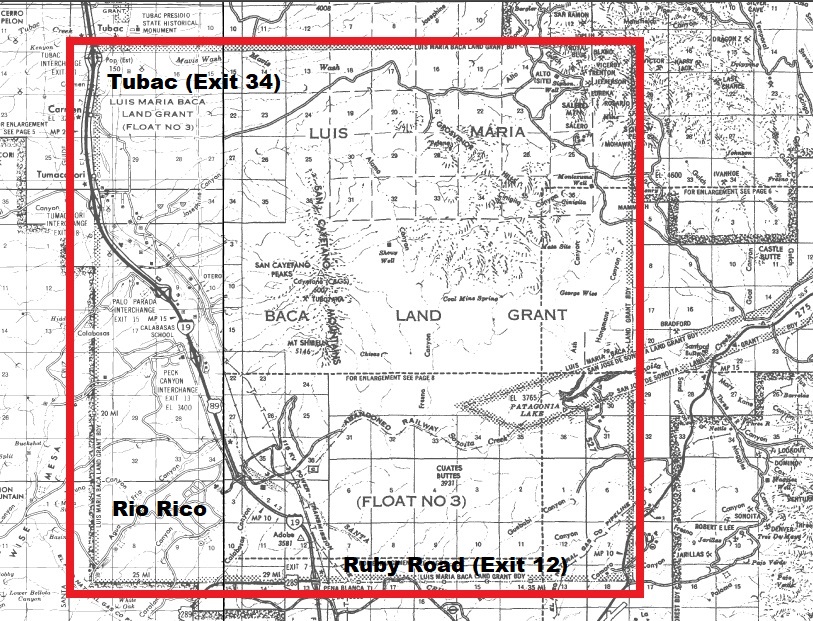

- What is now Rio Rico, Tumacácori and part of Tubac were formerly part of Baca Float #3 in the middle of the Santa Cruz River Valley

Key Terms

- Baca Float #3 – the 100,000 acre gift of land (or land grant) awarded by the U.S. Government in 1863 to private businessmen and which covered all of modern-day Rio Rico, Tumacácori, and part of Tubac. The U.S. awarded this land as compensation to the Luis Maria Baca family of Northern New Mexico for lands they lost in complicated disputes. In the 1910s early 200 families who already lived in the Santa Cruz River Valley later lost their lands to the businessmen who owned the Baca Float. Rio Rico was founded in the 1960s from Baca Float #3 property.

- Oral History – a way of studying history by interviewing people who personally experienced an event or who have a close perspective on it; this can be called living history as it involved speaking with people and learning their stories (such as our parents, grandparents, neighbors, etc.)

- Land Grant – a gift of land by a government to encourage settlement; the Spanish Empire, Mexican Republic, and U.S. Government all awarded land grants throughout the present-day U.S. West, including Santa Cruz County, Arizona.

- Homesteading – the act of someone (a homesteader) claiming unowned public land from the U.S. Government to farm or settle on it. The land where homesteaders live in is called a homestead.

- Patent – a set of documents confirming ownership of land.

- Due Process – the system where every individual has equal protection of the law, including the right to legally defend themselves or their property.

B-7 Special Focus: Recovering Justice via Family History in the Baca Float and the Santa Cruz Valley

Steve Gastellum, Retired National Park Ranger

Introduction

My parents and grandparents were witnesses to the tragedy of the Baca Float. They lived it and heard about it throughout their lives in discussions around the dinner table and from classmates. I learned about this because I was a student at my parent’s and grandparent’s knees hearing about this tragedy and reading what they wrote about their lives. I was literally fascinated and saddened with their life stories and was always willing to listen and ask questions about ranch and mining life. I could not get enough of it! Growing up, I was a big fan of Western movies and TV shows. I always tried to relate what I saw in the movies with what my parents and grandparents experienced.

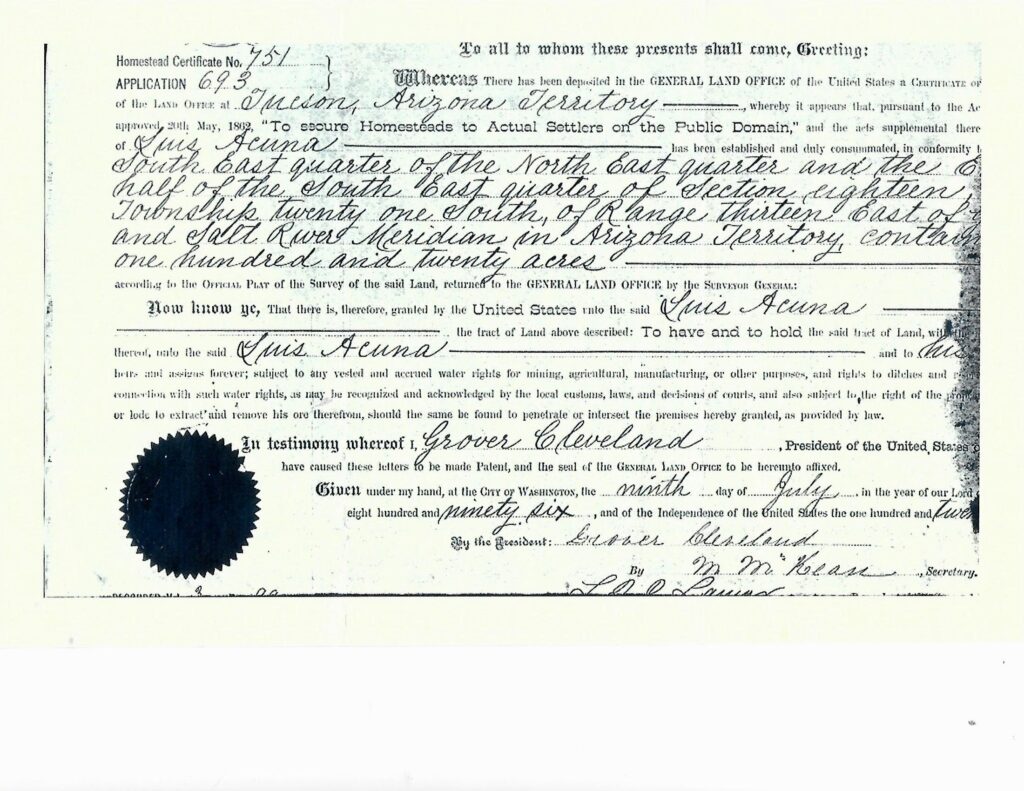

My grandparents were original homesteaders in the Arizona Territory, going all the way back to the 1880’s with my dad’s maternal grandfather who homesteaded 120 acres just south of Tubac. He, Luis Acuña, immigrated from Sonora, Mexico. Mom’s family, the Cotas, immigrated from Ures, Sonora, Mexico in the 1880’s and homesteaded in Carmen, near Tubac. The communities of Tubac, Carmen, Tumacacori and Calabasas were small, tight knit communities The homesteaders developed close ties with other settlers in the area. They traded with each other and celebrated births, baptisms, weddings and holidays together. Tragically, they also attended funerals within the community. Both families came from mining and ranching stock and this continued when they moved here. Francisco Cota, my mother’s father was a gold and silver miner and mined for these metals in the Santa Rita and San Cayetano Mountains. They mined at camps named, Total Wreck, Greaterville, Alto and Camp 49. They never got rich off their findings, but made enough to live on. Francisco and other miners knew of the mineral-rich deposits in the mountains surrounding the original Baca Float and it is a sure bet, the authorities who dealt with Baca Float #3 owner John Watts knew so, too.

When my grandparents decided to homestead in this area, little did they know how their lives would be totally upended when the Baca Float reared its ugly head! In this article, I will explain the human impact of the Baca Float #3 land fraud tragedy in Santa Cruz County.

What was the Baca Float?

My overview article – “What is the Significance of Baca Float #3?” – explains the confusing history of the Baca Float #3 land grant in greater detail, but it is important to summarize the main points here. Baca Float #3 was a 100,000-acre gift of land in the Santa Cruz River Valley by the U.S. Government to the heirs of Luis María Cabeza de Baca of New Mexico which included all of present-day Rio Rico and Tumacácori. The U.S. Government created this land grant (gift of land) to compensate the Baca family for lands they lost in Northern New Mexico. The U.S. Congress offered the Bacas compensation in the form of five separate 100,000-acre land grants known as the Baca Floats. In 1863 the Baca’s family lawyer, John Watts, selected the Santa Cruz River Valley along present-day Rio Rico as the site of Baca Float #3. The Bacas did not benefit from this as they sold Watts their rights to their property to pay their deep legal debt to him.

Baca Float #3 was first declared along the Santa Cruz River, but Watts and his business associates instead, wanted to change the grant’s location to include the Santa Rita Mountains and their minerals. For nearly fifty years, Watts and the company essentially abandoned the river farmlands which became the U.S. Government’s public domain. People flocked to the area, not knowing Watts still owned it. The U.S. allowed homesteading within the limits of Baca Float #3 at that time. Santa Cruz River homesteaders came from many backgrounds, but most were Mexican migrants from Sonora interested in the U.S. Government’s promises of land. Ownership of a homestead was confirmed by a patent or set of documents confirming land ownership. Homesteaders’ patents included the U.S. President’s signature.

After the courts denied Watts’s scheme to relocate the Baca Float into the mountains, Watts wanted all the homesteaders living in the 12.5-square mile area from modern-day Ruby Road to the edge of Tubac evicted. The U.S. Supreme Court decision in Lane vs Watts in 1914 gave Watts and his associates rights to the Santa Cruz River Valley’s best farmlands. To enforce his rights, U.S. Marshals came to the homesteads and in some cases forcefully removed them at gun point. They did not serve them with legal papers, just the point of a rifle! By telling the homesteaders to leave their lands, Watts could claim they abandoned their homesteads and then he had the right to claim them. Approximately 196 families were affected by the Baca Float #3 land grab scheme.

Case Studies of Baca Float Evictions

The U.S. Government’s forceful eviction of Santa Cruz River Valley families began in the 1910s. The events surrounding the following people are typical of how the “law” dealt with the homesteaders that were unjustly evicted from their lands following Attorney John Watt’s unethical land grabs.

Baca Float homesteaders were not given due process, a system for resolving legal disputes according to established rules with fair treatment for both parties. In all cases I have studied, armed U.S. Marshals came to the homestead and ordered the people off the land, often coming in the dead of night to harass the men and intimidate their families. None of these homesteaders received a written eviction notice. The residents were never told they had a right to appeal the eviction. This probably happened on purpose because once the homesteaders left the land, the law considered them to have abandoned their property, thus meaning they gave up their rights to it. The lack of a paper trail and U.S. Marshals not informing the homesteaders they had the right to appeal represent major violations of due process. Approximately 196 families in the valley were affected in one way or another.

The communities of Tubac, Carmen, Tumacacori and Calabasas were devastated. Friends and neighbors moved away. Many were too old to start anew. Families were fractured as relatives moved away to other places, never to return. Some families, too poor to resettle, became migrant farm workers chasing crops across the country. Children found it very difficult to attend school as their family had to labor hard to make a living elsewhere. The spirits of many were broken and many families broke apart due to the stress and loss of their homes and property.

The Acuña Homestead

Luis Acuña immigrated from Mexico to Arizona around 1880, eventually claiming a homestead just south of Tubac in 1882. He claimed 120 acres of rich bottomland adjacent to the Santa Cruz River. With Acuña came Santiago Gastelum who was 16 at the time. He became a foreman on his ranch helping him raise, brand and butcher the cattle. They herded them up to Amado Siding for the market. Santiago fell in love and married Acuña’s daughter, Santos. They lived on the homestead up to the time of Luis’ and wife, Josepha’s death in 1911 and 1915, respectively. Women could not inherit land, so the land went to Santiago. Together, they had nine children, although one died during the 1918 Spanish Influenza. They lived and worked the land continuously until 1919.

Then on an August night in 1919 at 11:30 PM, U.S. Marshals banged on the door of their house and ordered the family to leave their land. My grandfather, Santiago told the Marshals he had legal title to the land and showed them the homestead patent, signed by President Grover Cleveland in 1896. Santos had just given birth to Manuel, dad’s younger brother two weeks prior and she was recovering from surgery after a difficult birth. None of this mattered to the marshals. Santiago placed as many possessions on the buckboard wagon as he could, loaded up his 5 children, tethered several animals to it and left the land, never to return to the homestead. They moved five miles north to Reventon. Their school age children had to ride on the buckboard wagon or horseback 1 ½ hours to Tubac one way in all kinds of weather to attend school.

Santiago and Santos are buried in the old Tubac Cemetery. My father, Luis, was four years old at the time and all his life, he remembered the eviction. He talked and wrote about it extensively. It was a main topic of conversation at their home around the kitchen table. [1]

Aging and Nearly Blind School Teacher Thrown Off Her Land

Sarah Black taught in the old Tubac schoolhouse. She taught for many years, including Santos Gastelum and many other students of that era. She and her husband homesteaded 240 acres of bottom land near the Santa Cruz River. She and her husband planted tomatoes, barley, chilies and watermelon to sell at market. One day armed Federal Marshalls came to her home and ordered her off her land. She told them she had no place to go and no one to help her move her belonging out of the house. The Marshalls told her there was no problem; they could help her move. Proceeding into her home, they tossed her possessions onto the yard without regard for damaging anything. After they were done, they told her she was moved.

At the time of her eviction, she was nearly 92 years old and going blind. She had no one living with her and she was on her own. She later wrote” My land looked like an auction yard. They put everything out doors, the furniture and dishes and everything. It was the most brutal thing that ever happened. I don’t know as I cared so much, but it was pretty hard for the people who were too old to begin again”. She soon moved to a rented room at the Carmen store where she died. She is buried at the Tubac Cemetery.

My father’s mother, Santos, remembered Sarah Black as a stern woman, but she was a very good teacher! She expected a lot from her students, but was willing to help them learn the subject matter by providing extra help to them when they asked for it.

Sarah Black helped many homesteaders write letters of a legal matter regarding their homesteads and acquiring permission to from their neighbors to gain access to the Santa Cruz River to irrigate their crops. She was willing to help anyone who needed help and did not understand legal matters.

The Murder of Sonovio Villa

Sonovio Villa was my mother’s father’s (Francisco Cota) step nephew. They lived on adjacent homesteads on the western edge of the Baca Float. Villa’s family homesteaded 160 acres north of Tumacacori Mission. Their eastern homestead boundary abutted the western edge of the Baca Float. However, since they had no well, they obtained permission from their neighbor to construct an acequia (Spanish for shared irrigation canal) across their land to the Santa Cruz River to obtain water for their crops and animals. Sarah Black, the Tubac schoolteacher, helped Cota and Villa write the legal documents needed to gain permission to construct an acequia across their neighbor’s land. Permission was granted, they paid a fee for the use of the acequia and did the initial construction and maintenance on it. The acequia was located within the float boundaries. They were given a specific day and time to use the acequia, and if they did not use it that day, they had to wait until their next turn.

On June 12, 1925, Sonovio had to go to the river to open the compuerta (irrigation gate) so that water could flow to his land. Sonovio asked his uncle, Francisco, to go to the river with him. My grandfather decided to go with him because he had had an altercation at the river with local ranchers two weeks prior. Francisco did not want Sonovio to have the same problem. When Francisco went to open his compuerta to water his crops, two local ranchers told him, he could not use the water that day because they were using it. Cota told them, it was his day and time to use it and no one was going to stop him from watering his crops and animals. They threatened his life, but he got off his horse and proceeded toward the acequia. They put a pistol in his stomach and told him he was a dead man if he opened the compuerta. He knocked the gun out of their hands with a shovel he was carrying and kicked the gun into the water. He bent over the compuerta, opened it and remounted his horse and headed for home.

Sonovio’s incident was almost identical to Cota’s, except it took a deadly turn. The ranchers told Sonovio if he opened the compuerta he was a dead man. Sonovio got off his horse after they threatened him, opened the compuerta and remounted his horse. They were true to their word as they shot him in the back, killing him. He slumped over his horse and it bolted for home, Cota following close behind.

A “trial” was held for the ranchers at the 1904 County Courthouse, but Cota was never called as a witness and the ranchers got off from the murder charge. Sonovio’s death certificate read “Murder, gunshot wound”. The family never received compensation for his wrongful death. The law failed to uphold Sonovio’s right to use the acequia at his appointed time. He and his family are buried in the old Tubac Cemetery.[2]

Conclusion: Why Oral History is Important

The stories I have shared with you were first handed down to me by my parents and grandparents. The feeling and curiosity I felt hearing about these stories over the years (none of which were in any history books) made me want to learn more about this and share this story with others.

The Santa Cruz River Valley is a beautiful, peaceful area which makes learning about the abuses, fraud, and violence which took place here when Baca Float #3 was imposed on the community, all the harder to learn about. The Baca Float fraud did not stop in the 1920’s or 30’s. In 1960, when “modern Rio Rico” was established, fraud reigned supreme again. This time it involved a Florida land company, named Gulf America Corp. It was run by a group of crooks, too, whose main goal was to make money off unsuspecting clients by selling land which in many cases was undevelopable. Some of the land Gulf America sold people was on rock hard land, which would not allow the sewage from their septic systems to perc into the soil. This would make the parcel of land uninhabitable. There were no plans to build a village sewer system, so most parcels would have to rely on a septic system to get rid of waste. Some plots were located on steep slopes which would make building a home nearly impossible and very expensive if they could develop it at all by shaving off the top of the slope. The developers promised prospective land buyers’ electrical power, telephone lines, paved roads, and other amities, which they did not provide. They would fly people into Tucson and bus them to the area and wine and dine them at the Esplendor Resort. They would point to the area where their plot of land was located and that would be as close as they got to their parcel of land. Plots were sold and resold many times over. Many plots were never developed and remain empty to this day.

Oral history interviews are important ways of teaching us about important ideas and experiences through people that experienced an event – living history. Direct oral history accounts of the Baca Float #3 fraud are sparse, but some do exist at the Tubac Historical Society Research Library.

The oral histories which my parents and I documented were key to understanding the tragedies all these people felt upon their eviction. Oral histories, particularly taped histories are critical to understanding the feelings they felt, because the voice inflections give a clue as HOW the people felt. This feeling does not always come out in written interviews. What might you learn from speaking with your older family members about their history?

Nearly 200 families were affected by the Baca Float #3 land grab scheme in the 1910s, but very little is known about most of the families. When talking to various families “off the record” about this episode in their lives, they felt a lot of shame and helplessness in losing their land. This greatly affected the welfare of their families that in some cases lasted a lifetime. This may be the reason; some families refuse to document or talk about their hardship. Maybe your own great grandparents lived through some of this. The Baca Float story involved three countries and covered over 200 years without a satisfactory conclusion for the vast majority of families affected by expulsion. Perhaps in better understanding this complicated, but sad story we can better honor the memories of those who lost everything due to Baca Float #3.

About the Author

Gastellum’s family has lived in the Santa Cruz/Altar Valley continuously since 1737 and his grandparents and parents and grandparents in what was Baca Float #3 since the 1880’s. The author has lived in Rio Rico for 25 years. Steve worked for the National Park Service for 42 years and retired from Tumacacori National Historical Park in 2014. He has documented his parents’ and grandparents; stories about the Baca Float in several museum exhibits, with the help of family members and talks at Canoa Ranch, Tubac Presidio State Park and the Rio Rico Historical Society Museum.

Bibliography

Gastellum, Luis A. “Memories of My Youth In Tubac” Journal of Arizona History, Arizona Historical Society (Spring 1995) 1-32

Sheridan, Thomas E. Landscapes of Fraud – Mission Tumacacori, the Baca Float and The Betrayal of the O’odham. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2006.

Martin, Patricia Preciado. Beloved Land – An Oral History of Mexican Americans in Southern Arizona. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2004

Oral History Notes and tape recordings by the author of his parents and grandparents accounts of their lives in the valley.

Note

[1] Oral history communication between my father, Luis, and I about his early childhood in Tubac; Martin, Patricia Preciado, Beloved Land An Oral History of Mexican-Americans in Southern Arizona, Tucson, University of Arizona Press, 2004.

[2] Oral history communication between my grandmother, Lucinda Cota and my Mother Agatha Cota de Gastellum about events surrounding their decision to leave their homestead in 1925.