The Mexican Revolution, World War I, and the First U.S.-Mexico Border Fences

Carlos Francisco Parra, PhD

Miguel Grijalva (2024), Oil on Canvas

Key Concepts

- August 27, 1918, Battle of Ambos Nogales between U.S. Army and Mexican combatants profoundly transformed the two cities and led to the two Nogaleses becoming the first U.S.-Mexican border cities permanently divided by border fences

- 4 U.S. deaths; 13-129 Mexican deaths

- The 1918 Battle of Ambos Nogales was the result of rising tensions along the border during the decade of the Mexican Revolution and the U.S. entry into World War I

- Primary and secondary sources about the Battle of Ambos Nogales vary, although primary sources from the 1910s in both the United States and Mexico point to the tense atmosphere along the border during that time

Key Terms

- Mexican Revolution – a series of civil wars in Mexico from 1910-1920 aimed at creating political and social equality. The Mexican Revolution also led to violence along the U.S.-Mexican border and the immigration of hundreds of thousands of mexicanos into the United States

- factions – competing political groups

- World War I – a 1914-1918 global conflict between Imperial Germany and the Allied Powers; the U.S. fought against Germany from 1917-1918

- primary sources – written or verbal testimony of an event by direct witnesses

- secondary sources – testimony of an event by persons who did not directly witness it

- combatants – person fighting in armed conflict

- corroborate – prove

- Corrido – a form of Mexican musical storytelling via song; gained popularity during Mexican Revolution

- Corrido de Nogales – a storytelling song about the Battle of Ambos Nogales composed by unknown Mexican artists; different versions of the Corrido de Nogales exist

RESEARCH ARTICLE

B8. What is the Significance of the 1918 Battle of Ambos Nogales?

The Mexican Revolution, World War I, and the First U.S.-Mexico Border Fences

Carlos Francisco Parra, PhD

Introduction

Shots fired on the border! The echoes of machine gun fire echoing across the hills of Nogales! The bodies of young women and men laying on the ground. The mayor of Nogales, Sonora, killed by U.S. Army gunfire. The closed border leaving mexicanas and mexicanos stranded in the U.S. and sleeping on park benches. Military trains rushing in from Ft. Huachuca and Hermosillo. The threat of another U.S.-Mexican war right on the border of Nogales!

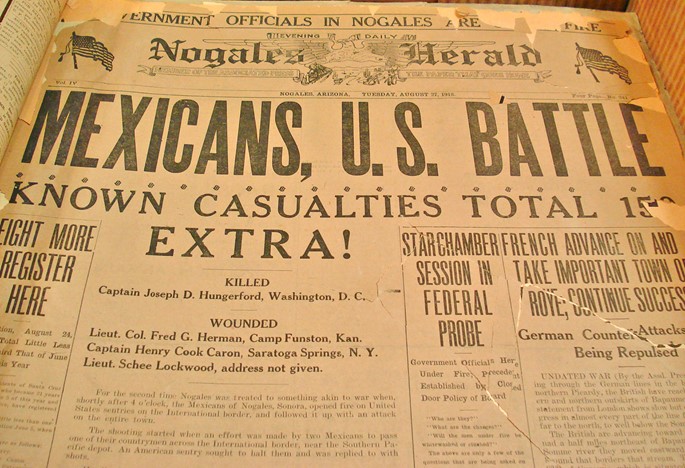

These were some of the moments from the August 27, 1918, Battle of Ambos Nogales fought between the U.S. Army and armed Mexican civilians after years of rising tensions during the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) and World War I. Four Americans and perhaps as many as 129 Mexicans died in the battle which left 330 people wounded after a mexicano walked into Mexico without being inspected by U.S. customs officers. There was no border fence when the battle took place, but a few weeks later Nogales would be forever divided by the first permanent border fence dividing a U.S.-Mexico community. Our home in Santa Cruz County and the borderlands of Mexico and the United States would never be the same.

Border Tensions during the Mexican Revolution and World War I

The Mexican Revolution of 1910-1920 was a series of civil wars in Mexico aimed at creating political and social equality. However, the Revolution also led to violence along the U.S.-Mexican border and the immigration of hundreds of thousands of mexicanos into the United States.

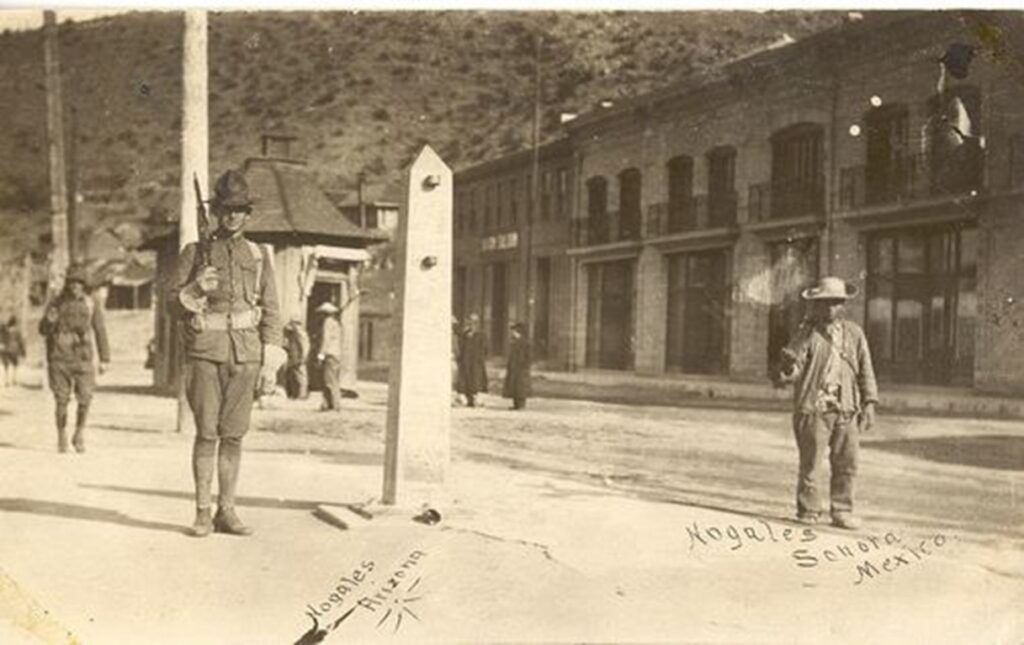

First exploding as a rebellion against Mexico’s Dictator-President Porfirio Díaz, the Revolution engulfed the U.S.-Mexico region as different Mexican factions (political groups) fought for control of cities like Nogales, Sonora and their access to U.S. trade. In 1913 and 1915, rival Mexican armies battled for control of the city. The Revolution’s violence created economic devastation and starvation, forcing millions of Mexicans to flee to the U.S., often passing through Nogales on the way to California. Border fences did not yet divide Ambos (both) Nogales.

As the Mexican Revolution damages U.S.-Mexico relations, the U.S. sent thousands of troops like the African American “Buffalo Soldiers” to guard the border. One of the worst moments of these tensions place in March 1916 when Mexican revolutionary leader Francisco “Pancho” Villa attacked the bordertown of Columbus, New Mexico. In retaliation, the U.S. Army pursued Villa by invading the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua from 1916-1917 without Mexico’s permission. The two countries nearly went to war. Villa, meanwhile, escaped capture, angering the U.S. public.

Border tensions increased in 1917 as Germany tried getting Mexico to invade the U.S. in a secret agreement known as the Zimmerman Telegram. Shortly afterwards the U.S. declared war on Germany, entering World War I.

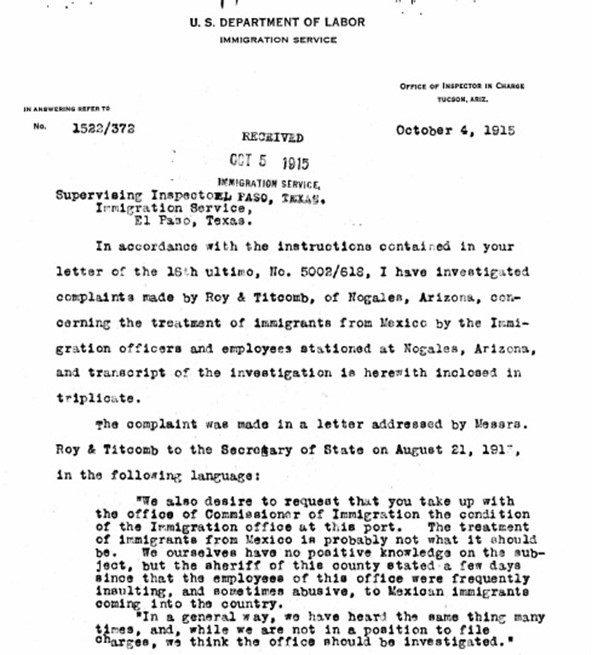

The open border began closing because of the war as the U.S. issued a new requirement that all citizens and foreigners have passports to enter and leave the country. Mexicans who crossed into Nogales, Arizona every day for work suffered from constantly changing passport rules. Impatient U.S. customs officers insulted and physically harassed mexicanos who didn’t understand the passport rules. The U.S. tried protecting wartime food supplies by limiting the number of times Mexicans with passports crossed the line. By August 1918, the U.S. Consulate distributed “food cards” to people in Nogales, Sonora who wanted to buy food for their families in Arizona. Despite Mexico’s severe food shortage, the U.S. limited Mexican grocery shoppers’ crossing to once per week.[1] Surviving primary sources (written or verbal testimony of an event by direct witnesses) in both the U.S. and Mexico document how racism and harassment at the border was common by U.S. customs agents against mexicanos who did not understand the passport or food card laws.

Tensions grew between Mexicans and U.S. troops in Nogales. In one instance, U.S. soldiers and Mexicans fought fistfights against one another during an August 14, 1915, riot along Morley Avenue which even national newspapers covered.[2] Years later, U.S. troops shot and killed two Mexican men on the Nogales border on Dec. 31, 1917, and March 22, 1918.[3] A third fatality was almost added in June 1918 when a U.S. soldier shot at Ygnacio Orozco after a miscommunication at the unfenced border. Nogales, Sonora, Mayor Félix Peñaloza defended Orozco and installed a short fence a few yards long on International Street as a response. Peñaloza hoped controlling the movement of foot traffic with a fence would prevent further shootings. Ambos Nogales was on the verge of exploding.

The Battle of Ambos Nogales

At 4:10 p.m. on Aug. 27, 1918, carpenter Zeferino Gil Lamadrid walked from Arizona towards the border. Gil Lamadrid, a Mexican citizen, carried unidentified contraband and avoided U.S. inspection. It is believed Gil Lamadrid was carrying banned revolutionary newspapers into Mexico. As the U.S. officers shouted and pointed their guns ordering him to return for inspection, Mexican customs guards told Gil Lamadrid to keep walking.

Although U.S. and Mexican primary sources differ, it appears that Mexican customs inspector Francisco Gallegos shot and wounded U.S. Army Private William Klint when he pointed his rifle at Gil Lamadrid. The shootout expanded as nearby U.S. troops exchanged gunfire with Gallegos and the other Mexican guards while Gil Lamadrid escaped. As the sound of gunfire echoed, dozens of civilian Mexican combatants (persons fighting in armed conflict) joined the fight, firing from behind buildings and sniping at U.S. troops from the surrounding hills.

Miguel Grijalva (2024), Oil on Canvas

“Buffalo Soldiers” from the segregated 10th Cavalry Regiment raced to fight. Although African Americans like Sgt. James Penny were not allowed into some Nogales, Arizona, restaurants, they still fought bravely. Capt. Joseph Hungerford, a white 10th Cavalry officer, died leading a charge up the hill east of Morley Avenue to stop the mexicanos’ sniper fire. Several cavalrymen were wounded, but the position was taken.

Hoping to prevent greater loss of life, Nogales, Sonora, Mayor Félix Peñaloza ran towards the battle. Waving a white handkerchief tied to a cane and pleading with the Mexican combatants to stop fighting, he was shot multiple times by U.S. gunfire just two blocks from the border, dying minutes later. Several Mexican women, two of whom were wounded, braved U.S. fire to rescue the injured.

A corrido (or Mexican storytelling song) composed soon after the battle and titled “el Corrido de Nogales” quoted the women. According to the “Corrido de Nogales” (a primary source), the women rescuers said: “No hay cuidado, somos puras mexicanas,” or “Don’t worry, we’re pure Mexican women.”

A white flag was raised over the Mexican customs house at 5:45 p.m. The U.S. Army closed the border until the afternoon of Aug. 28, leaving hundreds of Mexican workers stranded in Arizona, with many being forced to sleep on park benches overnight. Dozens of funeral processions took place in Nogales, Sonora, over the next two days as military trains from Hermosillo and the army base at Fort Huachuca arrived. Was this the start of a new war between Mexicans and Americans?

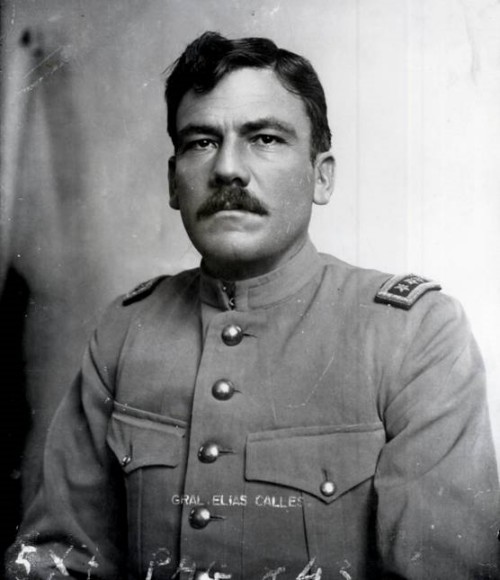

Despite the rumors, peace prevailed. Sonoran Governor (and future Mexican President) Plutarco Elías Calles and U.S. Gen. DeRosey Cabell met on International Street to discuss the conflict. Both regretted the violence and Calles, seeking to protect Mexico’s relationship with the United States, dismissed the Mexican civilian combatants as “irresponsible.”

Later histories of the battle based on secondary sources (testimony of an event by persons who did not directly witness it) claim the Nogales combatants were soldiers acting under the direction of German spies.[4] However, no evidence to corroborate (prove) this exists at the Pimeria Alta Historical Society, the Archivo Municipal de Nogales or the U.S. National Archives. According to U.S. newspaper articles before the battle, the majority of the Mexican Army in Nogales left to fight rebels near Sásabe, meaning that the Nogales fighters were mostly civilians angry about local border conditions and acting without orders.

As an example, four combatants barged into the U.S. Consulate and allowed all the staff to escape, except Elmer Cooley, a clerk known for harassing Mexicans when he worked as a customs agent. Despite his bullet wound, the U.S. government did not treat Cooley as a hero. As documented in the 1918 U.S. Army investigation of the battle, a primary source, U.S. Consul Ezra Lawton swore under oath that Cooley had a history of harassing mexicanos and even fired him from the Consulate after the battle.[5]

The First Real Border Fence

Hoping to avoid another battle, Calles and Cabell found a solution that has defined Nogales ever since: a border fence. The two-mile-long, six-foot-tall, barbed wire fence proposed by Calles and Cabell was installed that fall at a cost of $5,000 ($80,250 in 2018) and marked the first time a permanent fence separated two cities on the U.S.-Mexico border. (The barrier installed by Peñaloza was temporary). The 1918 Nogales border war created a fence trend that other cities like Douglas, Naco, and Calexico soon followed.

Conclusion

The Battle of Ambos Nogales has been mostly forgotten in the U.S., but the memory lives on in Heroica Nogales, Sonora, which the Mexican Congress officially renamed in 1961 in honor of the battle. A downtown monument with the Mexican eagle and serpent honors the dead. In the Colonia Héroes is the Panteón de los Héroes where many of the victims of the battle, including Mayor Peñaloza and customs guard Francisco Gallegos, are buried. Another grave near them is that of María Esquivel, a young woman killed during the battle either hanging clothes….or shooting back at the U.S. with her rifle! Esquivel’s mysterious story is the subject of the only documentary about the battle, Louis Hock’s La Mera Frontera (1997).

The tensions of the Mexican Revolution and World War I may be long in the past, but the August 27, 1918, Battle of Ambos Nogales – which led to the permanent border walls around us – continues shaping our community.

About the Author

Parra is a native Nogalian, former Nogales High School teacher, and an inaugural University of Arizona Presidential Postdoctoral Fellow. Currently he is an Assistant Professor in the University of Arizona Department of History.

Primary Documents:

Document 1:

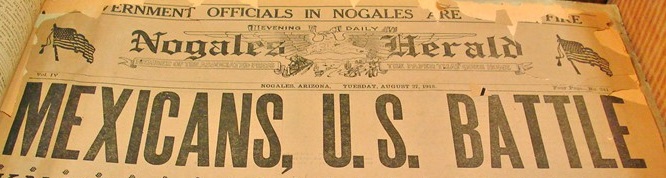

“Mexicans, U.S. Battle,” Nogales Herald, August 27, 1918, Evening Edition.

Document 2:

“Acontecimiento de Sangre en Ambos Nogales el Martes,” El Tucsonense, August 28, 1918

Document 3:

August 21, 1915, letter to U.S. Secretary of State from Roy and Titcomb Company of Nogales regarding harassment of Mexicans, quoted in October 4, 1915 Immigration Service Letter, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Document 4: El Corrido de Nogales

El Corrido de Nogales (1918); Lyrics from Antonio Avitia Hernández, Corrido Histórico Mexicano. Vol. 3: Voy a cantarles la historia, 1916-1924 (México, D. F.: Editorial Porrúa, 1998). Translated into English by Carlos F. Parra. [6]

Español

Valientes nogalenses

hicieron su deber

pelearon con los gringos

hasta morir o vencer.

Mil novecientos dieciocho

siempre te tendré grabado

ese pueblo de Nogales

con los gringos han peleado

Comenzaron a pelear

a las ocho de ese día ,

se escucharon por la línea

tiros de fusilería.

Al cruzar un mexicano

la línea divisoria

le pegó un balazo un gringo ,

fue el principio de la historia.

Cumpliendo con su deber,

Peñaloza corrió luego

a la línea divisorial

a ver si calmaba al pueblo.

Pero luego lo miraron

los malos americanos ,

ahí quedo bien tirado

en el suelo mexicano.

Eran mil quinientos gringos ,

todos eran federales

y no los dejó avanzar

ese pueblo de Nogales.

Hirieron a dos mujeres

las balas americanas ,

y dijeron “No hay cuidado ,

somos puras mexicanas.”

El que muere por su Patria ,

muere con todo honor,

al sepulcro lo acompaña

el pabellón tricolor.

Valientes nogalenses

hicieron su deber,

pelearon con los gringos

hasta morir o vencer.

El que muere por su Patria

muere con todo el honor,

al sepulcro lo acompaña,

el pabellón tricolor.

English

Brave Nogalians

fulfilled their duty

they fought against the gringos

to the death or to victory.

Nineteen eighteen

I will always have you marked

the people of Nogales,

with the gringos they have fought

They began fighting

at eight that day

from the border were heard

shots of rifle fire.

When a Mexican crossed

the boundary line

a gringo bullet hit him,

that was the start of the story.

Fulfilling his duty,

Peñaloza then ran

to the boundary line

to try to calm the people.

But then he was spotted

by the bad Americans,

and he was gun downed

on Mexican soil.

They were 1,500 gringos,

all were federal troops

and the people of Nogales

did not let them cross.

The American bullets,

they wounded two women,

but they said, “Don’t worry,

We are pure Mexican women!”

The one who dies for their Country,

dies with full honor,

the tricolor flag accompanies

them to the grave.

Brave Nogalians

fulfilled their duty

they fought against the gringos

to the death or to victory.

The one who dies for their Country,

dies with full honor,

the tricolor flag accompanies

them to the grave.

A recording of a slightly different version of the “Corrido de Nogales” is available in the 2002 Smithsonian Folkways CD album Heroes and Horses: Corridos from the Arizona-Sonora Borderlands [7]

Bibliography

Flores García, Silvia Raquel. Nogales, Un Siglo en la Historia. Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico: INAH-SEP, Centro Regional del Noroeste, 1987.

Noriega, Miguel. “Memories of 1918 Battle at Nogales,” in Oscar J. Martínez, ed., Fragments of the Mexican Revolution: Personal Accounts from the Border. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1983.

Parra, Carlos Francisco. “Valientes Nogalenses: The 1918 Battle Between the U.S. and Mexico That Transformed Ambos Nogales.” Journal of Arizona History, Vol. 51, no. 1 (Spring 2010) 1-32.

Tinker Salas, Miguel. In the Shadow the Eagles: Sonora and the Transformation of the Border During the Porfiriato. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Notes

[1] “May Close Border, Halt Food Runners,” Nogales Herald, June 22, 1918.

[2] “American Soldiers Riot in Streets of Nogales,” Los Angeles Times, August 15, 1915; “American Soldiers Fight with Mexicans,” New York Times, August 15, 1915; “A General Mix Up,” The Oasis (Nogales), August 21, 1915.

[3] “Local News,” The Border Vidette, January 5, 1918; “Mexican Shot by Sentry,” Nogales Daily Herald, December 13, 1917

[4] Examples of these secondary sources are Clarence C. Clenenden, Blood on the Border: The United States Army and the Mexican Irregulars (London: Macmillan Company, 1969) and Jane Eppinga, Nogales: Life and Times on the Frontier (Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 2002).

[5] “Report on Recent Trouble at Nogales, 1 September 1918,” Battle of Nogales 1918, Pimería Alta Historical Society, Nogales, AZ.

[6] Corrido de Ambos Nogales lyrics from Antonio Avitia Hernández, Corrido Histórico Mexicano. Vol. 3: Voy a cantarles la historia, 1916-1924 (México, D. F.: Editorial Porrúa, 1998

[7] “El Corrido de Nogales,” YouTube (May 20, 2015), (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kZCE9UTQiMM)