The Tragedy of Fraud and Violence against Santa Cruz County Families

Steve Gastellum, Retired National Park Ranger

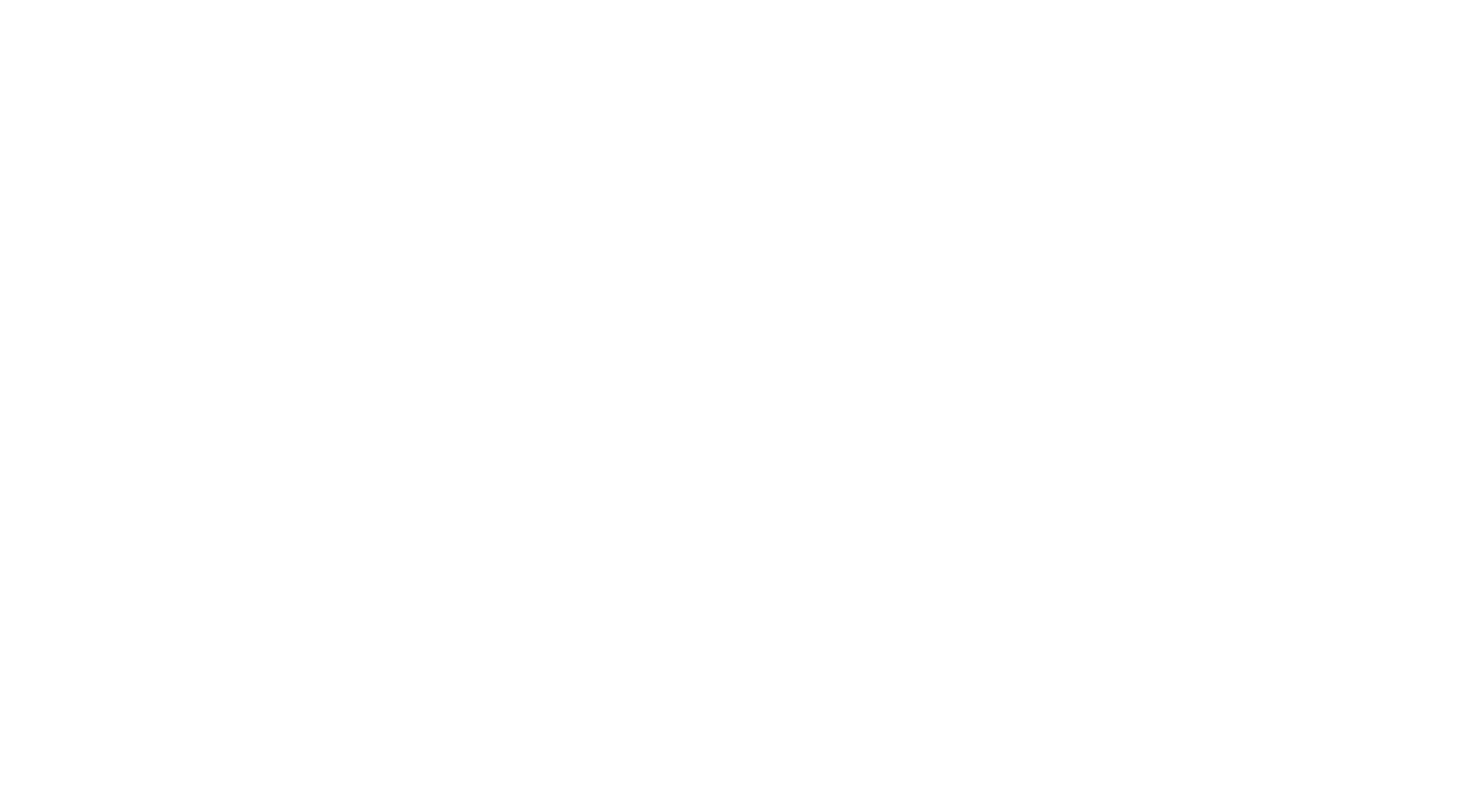

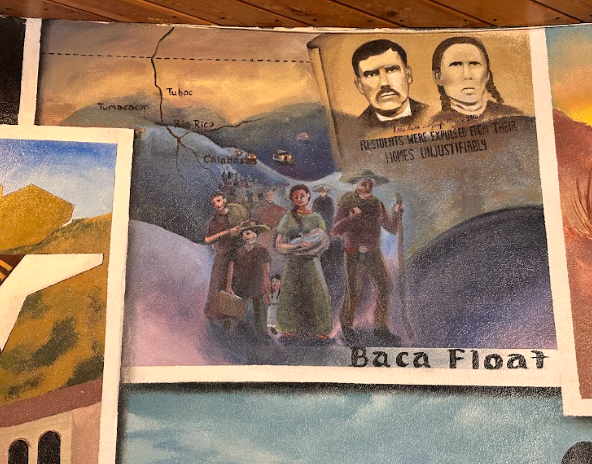

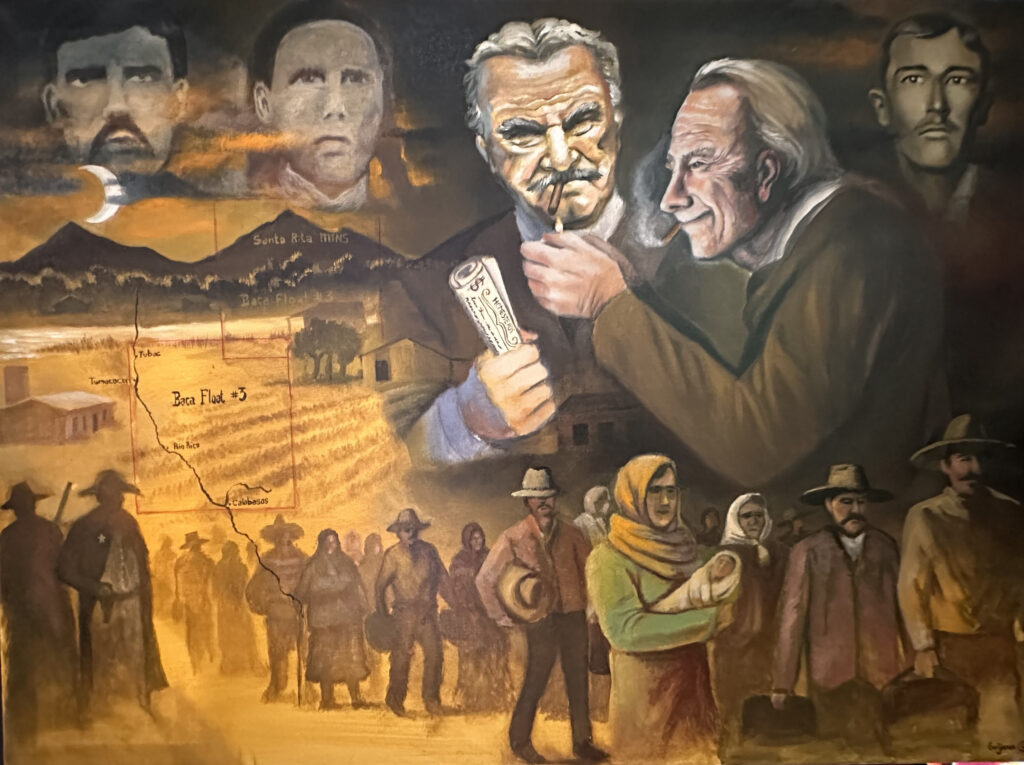

Violence against Families in the Santa Cruz Valley

Miguel Grijalva (2024), Oil on Canvas

Key Concepts

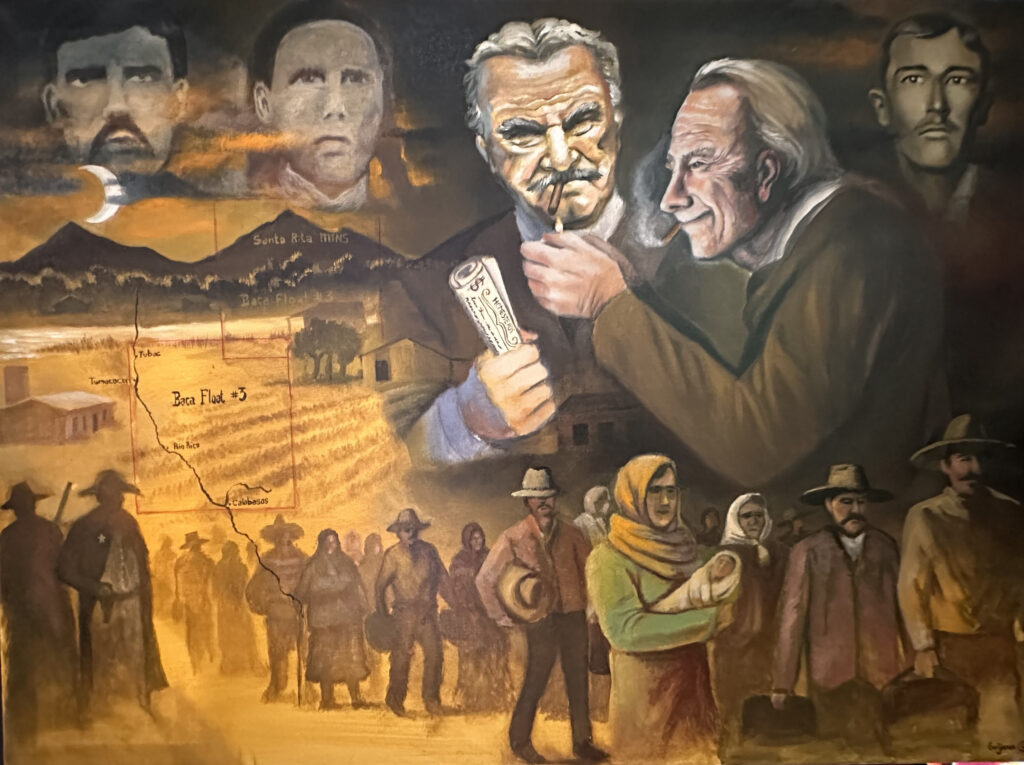

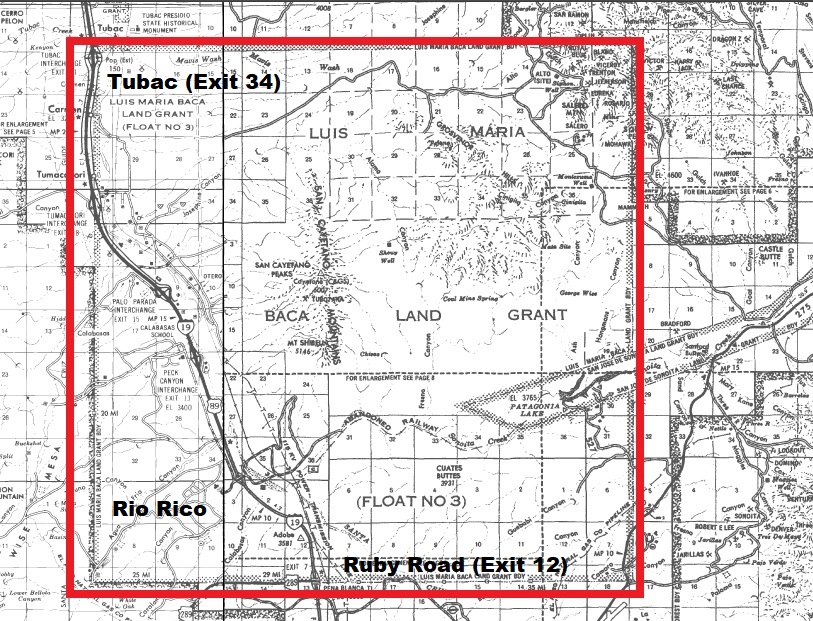

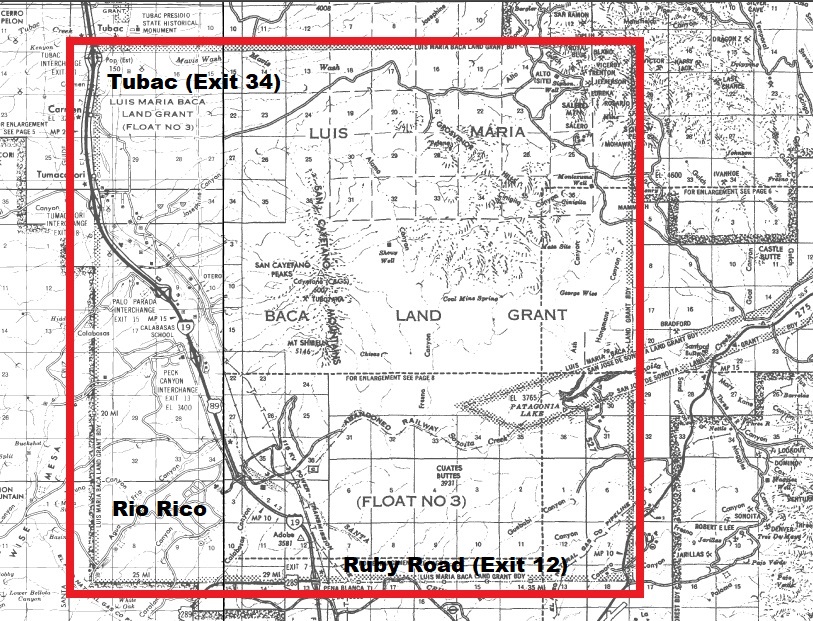

- The Baca Float #3 land grant is a significant aspect of Santa Cruz County history for being the basis for the modern-day origin of Rio Rico, the County’s largest population center

- Fraud and violence characterized the creation of Baca Float #3 which was meant as U.S. Congressional compensation for land lost by the Luis María Baca family of Northern New Mexico, but which ultimately greatly hurt families in Santa Cruz County

- Nearly 200 homesteading families along Tubac, Tumacácori, Carmen, and modern-day Rio Rico lost their homes to the Baca Float #3’s businessmen without due process

Key Terms

- Baca Float #3 – the 100,000 acre gift of land (or land grant) awarded by the U.S. Government in 1863 to private businessmen and which covered all of modern-day Rio Rico, Tumacácori, and part of Tubac. The U.S. awarded this land as compensation to the Luis María Baca family of Northern New Mexico for lands they lost in complicated disputes. In the 1910s early 200 families who already lived in the Santa Cruz River Valley later lost their lands to the businessmen who owned the Baca Float. Rio Rico was founded in the 1960s from Baca Float #3 property.

- Land Grant – a gift of land by a government to encourage settlement; the Spanish Empire, Mexican Republic, and U.S. Government all awarded land grants throughout the present-day U.S. West, including Santa Cruz County, Arizona.

- Las Vegas Grande Land Grant – a 500,000-acre land grant in Northern New Mexico offered by the King of Spain in 1821 to Luis María Baca located east of Santa Fe. After the Bacas abandoned the grant due to indigenous Comanche raids, other Hispanic families moved into the land and founded the town of Las Vegas, New Mexico. The Bacas’ attempt to regain their land decades later when New Mexico became part of the U.S. led to Congress compensating the family with five 100,000-acre land grants, including Baca Float #3 in Arizona.

- Homesteading – the act of someone (a homesteader) claiming unowned public land from the U.S. Government to farm or settle on it. The land where homesteaders live in is called a homestead.

- Patent – a set of documents confirming ownership of land.

- Due Process – the system where every individual has equal protection of the law, including the right to legally defend themselves or their property.

- Invalidate – to legally cancel something on a technicality.

What is the Significance of Baca Float #3?

The Tragedy of Fraud and Violence against Santa Cruz County Families

Steve Gastellum, Retired National Park Ranger

Introduction

It’s dark when violent banging on your door awakens you and your family. Forcefully knocking on a door so late at night is never a good thing. It’s a federal policeman – a U.S. Marshal – with a badge and guns. He and his fellow marshals have come to tell you that your family is living on land which doesn’t belong to you. The U.S. Supreme Court itself just decided the land you built a ranch on for the past 30 years is not actually yours. The Marshals impatiently explain that your land is part of something called Baca Float #3 which some businessmen want. You have only a few minutes to pack everything you can on a wagon before the Marshals evict you from your home. This is happening to all your neighbors too.

This is the history of our community in the Santa Cruz River Valley. This is what happened to my parents. They lived it.

The fraudulent and violent history of Baca Float #3 is important to understand because of how Rio Rico, Santa Cruz County’s main and fastest-growing population center, rose from it. We can’t forget the violence local families suffered because of Baca Float #3. This is the story of the Baca Float tragedy.

What was Baca Float #3? An Overview

Baca Float #3 was a 100,000 acre gift of land (or land grant) awarded by the U.S. Government in 1863 to a group of businessmen which covered all of modern-day Rio Rico, Tumacacori, and part of Tubac. Some of the County’s best agricultural lands – located right along the Santa Cruz River and the arroyos coming down the Santa Rita and Tumacacori Mountains – were all contained within Baca Float #3. Although the U.S. Congress created this property to compensate a Northern New Mexico Hispanic family, the Bacas, for vast lands they lost in complicated disputes, Baca Float #3 became the property of lawyers and businessmen led by John Watts who bought out the Baca heirs for approximately one cent per acre and used the land to fraudulently enrich themselves.

Baca Float #3 gave Watts great farming land around the Santa Cruz River, but he was less interested in the farming aspect of the land and was more interested in the rich mineral laden Santa Rita Mountains. Watts knew the mountain area well and once proclaimed they were the most mineral rich lands in Arizona! To this end, he fraudulently tried to get the U.S. Government to change the property’s location to include the Santa Rita Mountains. From the 1860s-1910s Watts and other businessmen unsuccessfully claimed the mountains and their mines as their own while they abandoned the lands by the Santa Cruz River. During this time many farmers and ranchers, known as homesteaders, moved into what they thought was empty land. They had the blessing of the US Supreme Court who encouraged the homesteaders, many of them Mexican immigrants, to start peaceful new lives by the river.

By the 1910s, however, the businessmen who legally owned the Baca Float gave up trying to take over the mines and suddenly wanted the Santa Cruz River farmlands they abandoned for so long. In the 1914, Lane vs Watts, the U.S. Supreme Court took the businessmen’s side and ordered the eviction of the Baca Float homesteaders from Tubac south through Calabasas, now known as Rio Rico. The evictions violently affected the lives of families who made (and lost) their home here.

Why was Baca Float #3 created?

The origins of Baca Float #3 in Santa Cruz County are complex and date back to the final years of Spanish rule in North America. The Spanish Empire often offered colonists a land grant (gift of land) to help settle territories it wanted to control. Vast areas of what are now Texas, California, and New Mexico were settled by Hispanic colonists via land grants. In 1821, right before Mexican independence that year, the King of Spain awarded Luis María Baca the 500,000-acre Las Vegas Grandes Land Grant, a massive property in Northern New Mexico. The grant’s name came from the well-watered, fertile meadows (vegas in Spanish) found on the property located east of Santa Fe. The Bacas were supposed to live and farm the land continually but abandoned it after raids by Comanche Indians.[1] Years passed and soon other Hispanic families moved into the Baca’s former lands. The settlers founded a new city, Las Vegas, Nuevo México (unrelated to the more famous city in Nevada). As the new town grew and the U.S. took possession of New Mexico from Mexico in 1848, the Bacas still claimed the land as theirs. The case then went through the U.S. courts for several years.

Finally in 1860, the U.S. Congress passed a law giving the Baca heirs five separate floats (or awards) of land as compensation for losing the Las Vegas land grant. To avoid future conflict between the two disparate parties, the US government decided to allow the people now living in Las Vegas, Nuevo Mexico to remain there. The Baca family’s lawyer, John S. Watts, picked the site of Baca Float #3 right in the middle of the Santa Cruz River Valley in Arizona on June 17, 1863. The four other Baca Floats were located throughout Northern Arizona, New Mexico, and Southern Colorado.

Baca Float #3 in the Santa Cruz River Valley

Can you imagine the U.S. government awarding you 100,000 square acres of land? That size of that land is so large that each side of the square-shaped property would be 12.5 miles long on each end. You might almost feel like royalty!

It’s not clear if the Bacas felt like royalty, though, as the family sold their rights to the land grants the U.S. Congress awarded them. Due to expensive lawyers’ fees, the Bacas sold their lands to lawyer John S. Watts who enriched himself using his clients’ vast properties to enhance his own holdings. The Bacas in faraway Northern New Mexico probably never even visited Baca Float #3. This land-loss happened to many other Mexican families in California, New Mexico, and Texas who had to go to court to prove they owned their land after the U.S. took the region from Mexico. With little cash to pay back the lawyers who were “protecting” their land, many Mexican families paid their legal debts by selling their lands to their own lawyers.

Selecting the site of Baca Float #3 in 1863 was also fraudulent. The law creating the Baca Float required that the selected site be vacant, and non-mineral, but the first site Watts picked along the Santa Cruz River already had many older Tohono O’odham and Mexican families living there, especially around Mission Tumacácori and the ruins of Mission San Cayetano de Calabasas as well as the Salero Mine. Baca Float #3 overlapped with older land grants the Mexican Government awarded in the 1820s-1840s, such as the Tumacácori, Calabasas, and Sonoita grants as well as the established communities of Tubac, Tumacacori and Calabasas.

Although Watts and his business partners selected the river valley, they were actually less interested in the farmland because they were mining speculators. They actually had their sights on mining in the nearby Santa Rita Mountains and, in a confusing twist, also tried convincing the U.S. Government that the original Baca Float site along the Santa Cruz River was in the wrong spot. Watts was actively ripping off the U.S. while the residents of the Tumacácori, Calabasas, and Sonoita grants fought for their land in court.

As the complicated dispute slowly crawled through the courts, the U.S. Government allowed farmers and ranchers to homestead within the Baca Float #3 location along the Santa Cruz River after Watts and company abandoned their efforts to settle on and improve upon the original Float location. Homesteading is the act of someone (a homesteader) claiming unowned public land from the U.S. Government to farm or settle on it. The land in which a homesteader lives is called a homestead. To earn title (ownership) of the land, homesteaders had to obtain citizenship, grow and/or raise livestock on it and build a home, out-buildings, and fencing. Homesteaders also had to survey (measure) the land. After many years working and living on the land, homesteaders were granted a patent, or document confirming property ownership, signed by the President of the United States. Imagine having your land confirmed by a presidential signature? Seven presidents signed homestead patents over the course of this time.

My great grandparents received a patent from President Grover Cleveland confirming their ownership of a homestead within the Baca Float. Indeed, the rich lands around the Santa Cruz River were very inviting for families from Sonora, Mexico, and around the U.S. Unfortunately, having patents with the U.S. President’s signature didn’t protect them from losing their homestead ranchos through fraud and violence.

1914 Supreme Court Decision and Homesteader Evictions

Although Watts schemed to get richer by moving Baca Float #3 into the mountains and controlling the mines there, the courts did not allow the change to move forward. Instead the courts decided 33 years later that Baca Float #3 was correctly located along the Santa Cruz River. Moreover, the U.S. courts invalidated (legally cancel on a technicality) the older 1820s-1840s Mexican land grants at Tumacácori and Calabasas in favor the 1863 Baca Float #3. Consequently, John H. Watts fought to evict all of the homesteaders who had moved into the Santa Cruz Valley over the previous fifty years. Lawsuits again! However, in 1914 the U.S. Supreme Court ordered that homestead patents within Baca Float #3 be terminated. The great eviction of homesteaders began. Where would the homesteading ranchero families go? Well, that was my family’s problem.

Violence against Families in the Santa Cruz Valley

Miguel Grijalva (2024), Oil on Canvas

Supported by the Supreme Court, Watts got U.S. Marshals to evict 194 families from their homes along the Santa Cruz River. Independent ranchero/homesteading families were impoverished by the sudden evictions which often took place at night. My great grandparents were among those evicted. There was no due process (or equal protection of the law) for my family. The story of their humiliating midnight eviction was told to me many times when I was growing up. Something similar happened to Charles Sykes, the founder and owner of the little town of Calabasas, who also lost his land. Having started Calabasas, one of the first towns in Santa Cruz County, didn’t protect Sykes from losing his land to Baca Float #3.

As Watts and his partners took over Baca Float #3, they took up the best agricultural lands in Santa Cruz County. Most of these evicted families had to move far away to restart their lives. A later 1921 law entitled “An Act for the Relief of Settlers” passed by Congress offered land in Buckeye (west of Phoenix) to many evicted families. It’s not clear from my research how many actually benefitted.

Conclusion

Driving along Interstate 19 today one can see a beautiful mix of ranches, fields, and little homes along the slopes of the Santa Cruz Valley’s mountains. Who would think that this area was all once part of a single property with a complicated history going back to Spanish-era New Mexico? Or that homesteaders with patents signed by the U.S. President would be evicted on behalf of a company which engaged in fraud? It is important to note, this fraud involved three countries – Spain, Mexico and the U.S. – covered 200 years of history, affected approximately 196 families with basically no compensation for the greatest number of affected families.

Baca Float #3 became the basis for the modern-day community of Rio Rico as the float’s later owners sold the land grant to housing developers from Florida in the 1960s. Reflecting much of the Baca Float’s earlier fraud, the Florida-based land developers also practiced fraud in ripping off homeowners during Rio Rico’s initial construction. This is a sad legacy which is still present in the Santa Cruz River Valley.

Understanding our history, particularly the erased part of our past, is important for us to understand where we are going as a community. As Rio Rico continues growing as Santa Cruz County’s largest community, it’s critical that we recognize how our history evolved, because it can help us build a better future. The humiliation and violence experienced by families in Rio Rico, Tumacácori, and Carmen in building our community should not be forgotten.

About the Author

Gastellum’s family has lived in the Santa Cruz/Altar Valley continuously since 1737 and his grandparents and parents and grandparents in what was Baca Float #3 since the 1880’s. The author has lived in Rio Rico for 25 years. Steve worked for the National Park Service for 42 years and retired from Tumacacori National Historical Park in 2014. He has documented his parents’ and grandparents; stories about the Baca Float in several museum exhibits, with the help of family members and talks at Canoa Ranch, Tubac Presidio State Park and the Rio Rico Historical Society Museum.

Bibliography

Gastellum, Luis A. “Memories of My Youth At Tubac” The Journal of Arizona History, Arizona Historical Society (Spring 1995) 1-32

Sheridan, Thomas E. “Landscapes of Fraud – Mission Tumacacori, the Baca Float and The Betrayal of the O’Odham”, Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2006.

Martin, Patricia Preciado. “Beloved Land – An Oral History of Mexican Americans in Southern Arizona, Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2004

Oral History Notes and tape recordings by the author of his parents and grandparents accounts of their lives in the valley.

Note

[1] Sheridan, Thomas. Landscapes of Fraud-Mission Tumacacori, The Baca Float and The Betrayal Of the O’odham. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2006