Kyle Kersey, University of Arizona

Key Concepts:

- The Grand Avenue School was a segregated primary school in Nogales founded in 1924 and closed in 1952.

- Arizona has a long history of segregation, including the segregation of public schools, movie theaters, restaurants, and hotels, as well as laws forbidding interracial marriage.

- Charles Mingus was a critically acclaimed jazz bassist, composer, and bandleader who was born in Nogales to a mixed-race family.

- Frank Reed was the first Nogales resident to die in World War II; the Grand Avenue School was renamed in his honor.

Key Terms

- Jim Crow South – Southern states that passed Jim Crow laws, which enforced the segregation of African Americans

- Avant-Garde Jazz – An innovative genre of music that expands beyond the traditional forms of jazz

- Camp Little – A segregated Army Camp that was home of African American regiments such as the Tenth Cavalry and Twenty-Fifth Infantry

- Buffalo Soldiers – African American soldiers who aided in westward expansion after the Civil War

- Poll Tax – a fee paid for the right to vote; used to prevent African Americans from voting after the Civil War

- Segregation – The separation of people into racial groups; used to discriminate against African Americans and prevent them from having access to the same public spaces and services as white people

- Color-barrier – The informal rule that excluded African Americans from Major League Baseball; led to the formation of African American only leagues called the Negro Leagues

- Saxophonist – A person who plays the saxophone

C-1 Special Focus C: Notable African Americans in Nogales and Local Segregation

Kyle Kersey, University of Arizona

Introduction

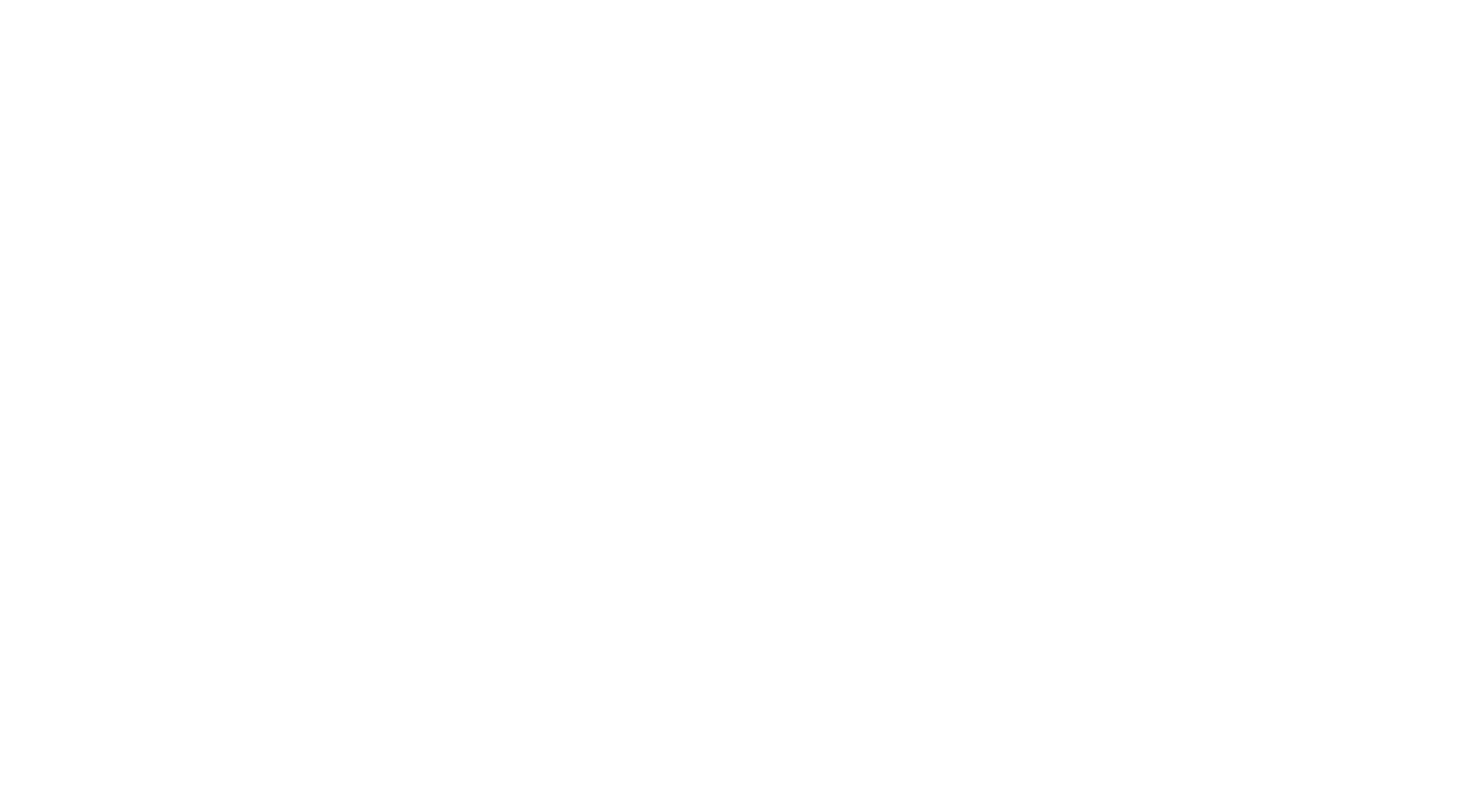

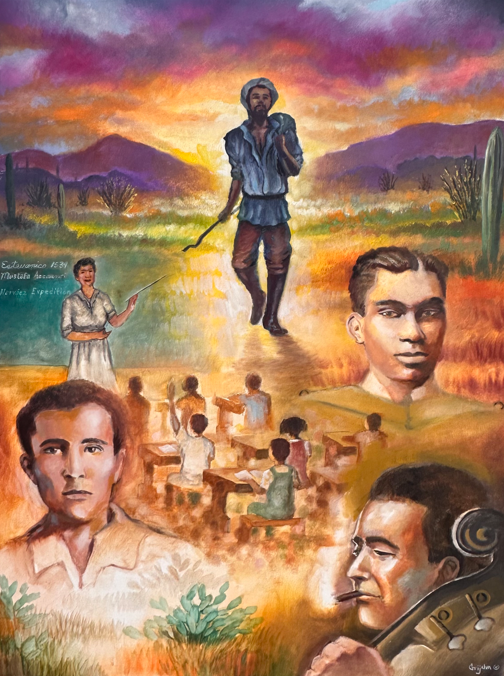

Our African American Heritage in Santa Cruz County

Miguel Grijalva (2024), Oil on Canvas

The border town of Nogales, Arizona, has long celebrated its bicultural U.S. and Mexican/Hispanic heritage as a sign of it being a welcoming community for all. While unique in many respects, the experiences of African Americans in Nogales in the earlier 1900s shows a different side of this community. Although the number of Black residents in Nogales is small now, the presence of the segregated African American “Buffalo Soldier” U.S. Army units at the small base at Camp Little along what is now Western Avenue in central Nogales gave the city a sizable African American presence.

As in most U.S. communities before the Civil Rights Movement, African Americans in Nogales went through a mix of good and negative experiences, including attending segregated schools. Nogales’s African American heritage, as seen in the experiences of Frank Reed, Charles Mingus, and the segregated Grand Avenue School, is a unique story which goes beyond many racial, social, and cultural fronteras.

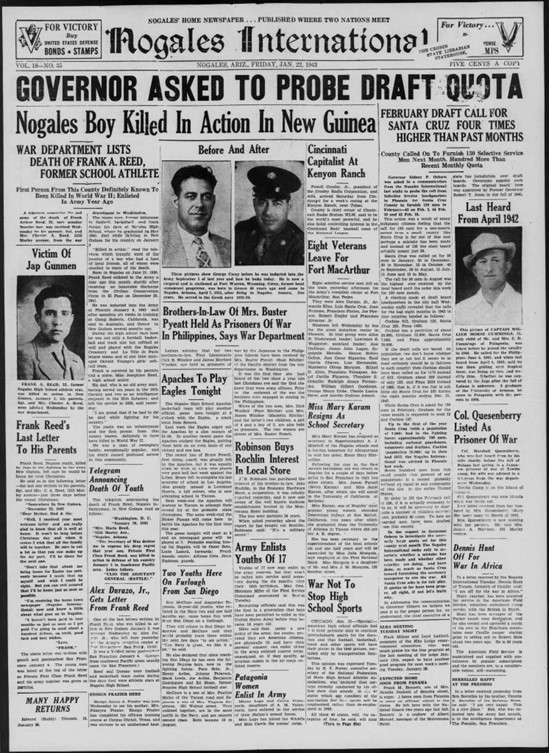

Frank Reed: Youth, Segregation, and Sacrifice

It’s early January of 1943. Chester A. Reed and his wife, Maria, receive a letter from their 22-year-old son, Frank, who’s currently fighting the Japanese in New Guinea. In his letter, dated December 22, 1942, Frank predicts that he’ll be home before next Christmas, writing “It won’t be long before Christmas day and when it comes I wish that all the family will be together. Be sure to eat a lot so that you can make up for my part. I’ll be there for the next one.”

A standout football, basketball, and track and field athlete at Nogales High School, Frank Reed enlisted in the Army a year prior. As a child, he attended the Grand Avenue School, the local Nogales elementary school for African American students, despite being ethnically Mexican. This was because Chester, an African American man, wasn’t his biological father, but instead married Frank’s mother, a mexicana, while he was a soldier at Camp Little after Frank was born. Chester gave Frank his last name and, in the eyes of the community, that made Frank an African American too.[1] And because Arizona law mandated the segregation of elementary schools, that meant that little Frank wasn’t allowed to attend school with his non-Black peers.

A few days later in 1943, Chester and Maria receive a telegram from Washington, D.C. It reads, “The Secretary of War desires me to express his deep regret that your son, Private First Class Frank Reed, was killed in action in defense of his country January 2 in the Southwest Pacific area.”

Frank Reed is the first casualty of World War II from Santa Cruz County. When asked by the local newspaper to respond to the news of his son’s death, the elder Reed, a veteran of the Spanish-American War and proud military man himself, displays his patriotism: “I am proud that if he had to die, he died while fighting for his country.” [3]

The intersection of the military and African American communities of Nogales is not unique to the Reeds. From 1910 to 1933, Camp Little was the home of African American “Buffalo Soldier” regiments such as the Tenth Cavalry and Twenty-Fifth Infantry. An article in the Arizona Republican estimated that there were more than 2,000 African Americans stationed at Camp Little in 1921.[4] Some of them settled in the area after their military service ended. What makes Frank Reed’s story even more unique is that the segregated Grand Avenue School he attended as a Mexican youth while being discriminated against as an African American due to racism beyond his control, was renamed in his honor in March 1943 (the access road to present-day Nogales High School is also named after Frank Reed).[5]

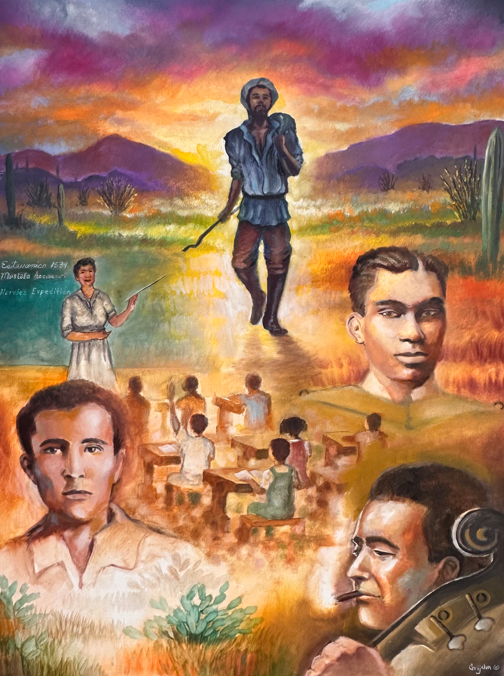

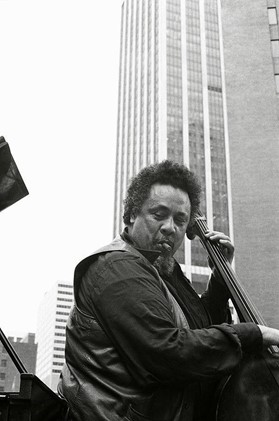

Charles Mingus: The Angry Man of Jazz

Known as much for his explosive temper as his compositional brilliance, Charles Mingus is regarded as one of the great jazz bassists, composers, and bandleaders of the 20th century. Born Charles Mingus Jr. in Nogales on April 22, 1922, Mingus was the son of a Buffalo Soldier stationed at Camp Little as part of the Tenth Cavalry. Mingus grew up in a mixed-race family: his father, Charles Mingus Sr., was the son of a former slave and a Swedish woman, while his mother, Harriet, was born in Hong Kong to a Black father and a Chinese mother.[6] His family moved to Watts, California shortly after he was born where, at the age of eight, he picked up the trombone. At 16, he picked up playing the standup bass, on which he would become one of the most acclaimed players in the history of jazz.

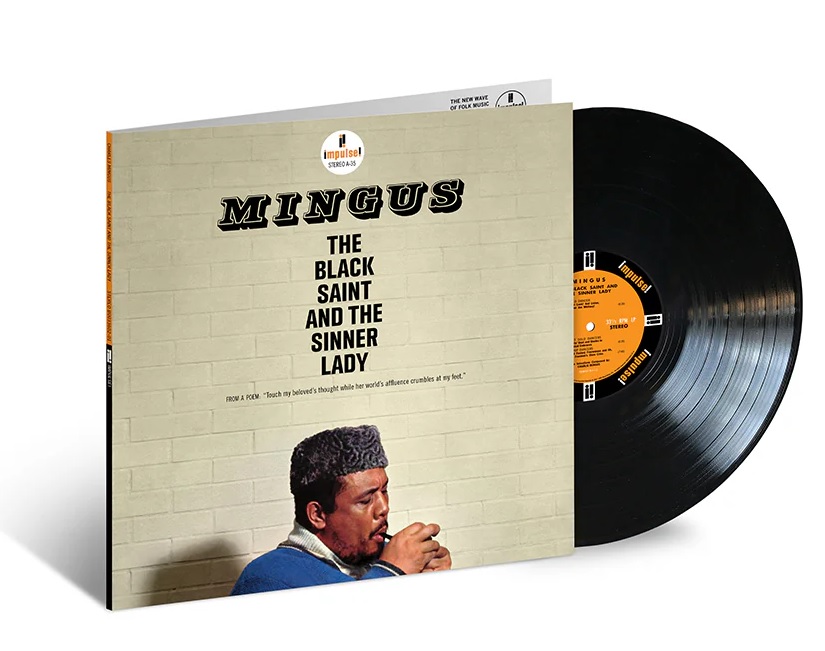

His 1963 album, The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady is widely considered to be one of the greatest avant-garde jazz records ever recorded, showcasing Mingus’ compositional complexity and instrumental intensity. Other seminal works include Mingus Ah Um, Blues & Roots, and Let My Children Hear Music.

Legendary Jazz critic Gary Giddens once described Mingus as “the best example we have of disciplined turmoil.” Giddens went on to write, “Charles Mingus and his music gave the impression of howling assurance and terrifying emotions. His bass echoed like a giant’s threat, to be soothed by his balmy melodies. More than any other jazz composer of his generation, he was willing – determined – to confront his fears and force his musicians to confront theirs.”[8]

That confrontational aspect of Mingus was reflected in his unpredictable temper. He once knocked out two of saxophonist Jackie McLean’s teeth because he’d given his two weeks’ notice. McLean returned the favor by stabbing Mingus in the stomach with a knife. Another saxophonist, Jimmy Heath, once said that he didn’t want to play with Mingus even though he loved his music because he was “intimidated by him.”[9]

Though his time in Nogales was short, Charles Mingus’ upbringing was representative of the mixed-race households that were prevalent throughout Nogales. In his autobiography, Beneath the Underdog, Mingus grapples with his own sense of identity and the discrimination faced as a Black man in a White-dominated society. Today, if you visit 10 W. Western Ave in Nogales, you’ll find Mingus Memorial Park, built where the entrance of Camp Little once stood. [10] Since the 2010s, Nogales has hosted an annual jazz festival in April to commemorate Mingus’ birthday.[11]

A Brief History of Segregation in Arizona

Everyone knows about Jackie Robinson, who broke the color-barrier when he started a game in 1947 for the Brooklyn Dodgers of the National League, becoming the first African American player in Major League Baseball history. However, far fewer people know about Larry Doby, who was the first African American to play in the American League.

In 1947, Doby signed a contract with the Cleveland Indians, owned by Bill Veeck. Years prior, Veeck had owned the Milwaukee Brewers. The team played their Spring Training games in Ocala, Florida, where Veeck was confronted with the realities of the Jim Crow South after accidentally sitting in the segregated section of the stands, causing an argument with a local sheriff and, eventually, the mayor himself.[12] When Veeck bought the Indians in 1947, he moved their Spring Training to Tucson, in part because he owned a ranch there and in part because he didn’t want Doby to suffer the indignities of southern segregation. However, when Doby arrived in Tucson, he was told that he couldn’t stay at the Santa Rita Hotel because he was black, and arrangements had to be made for him to stay with a local black family.[13]

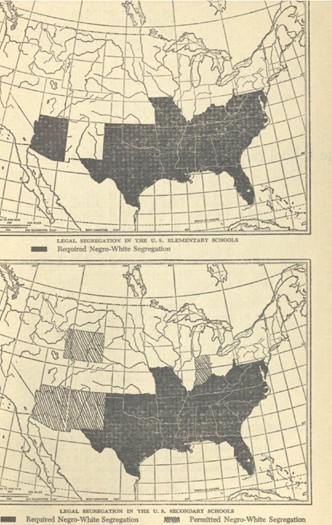

Arizona’s history of educational segregation dates back to 1909, when a pre-statehood territorial assembly passed a law “permitting school officials to segregate African American pupils in public schools despite their low proportion of the state’s population at 1.5 percent.” Section 54-416 of Arizona State Law stated that school trustees “shall segregate the pupils of the African race from pupils of the Caucasian race in all schools other than high schools, and provide all accommodations made necessary by such segregation.” In 1934, this was interpreted by the Arizona Supreme Court to mean that trustees “must segregate Negro students and provide separate accommodations for them even though only one such student is enrolled.”[14] While Wyoming and New Mexico allowed for the segregation of elementary schools, Arizona was the only state in the West that required it.

Figure 3: A map of the states enforcing segregation in public schools found in a 1949 report by the Arizona Council for Civic Unity. Seen here is the geographic disparity between Arizona’s laws regarding educational segregation and those of its western neighbors.[15]

Segregation wasn’t limited to education, either. The 1912 Arizona Constitution prohibited intermarriage between whites and African Americans. Movie theaters, restaurants, and hotels were also often segregated. When a committee from the Urban League of Tucson asked a theater manager to desegregate his establishment, he replied, “I’d like to oblige you, but you can’t expect us to not segregate when the state law and policy provides for segregation in schools. Get the school laws repealed first, and then we can talk this thing over.” [16]

Unlike the Jim Crow South, Arizona never instituted a poll tax to disenfranchise Black voters. Arizona also didn’t mandate the segregation of its high schools, though it did allow for localities to do so.

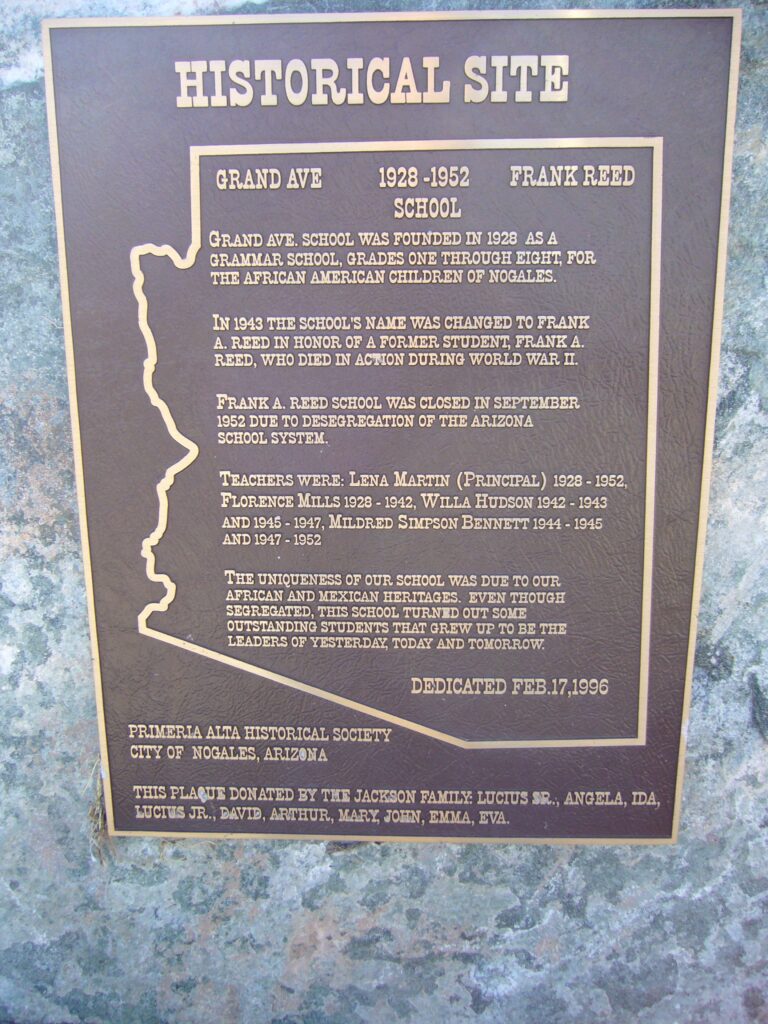

The Grand Avenue/Frank Reed School

Opened in 1924, the Grand Avenue School, referred to as “the colored school” by Nogalians, was the only segregated school for African American children in Nogales. It served students from 1st through 8th grade and fed into the Nogales High School, which was not segregated. As may be remembered, the school was renamed in 1943 after Frank Reed’s death in World War II.

Nogales had a relatively small African American population. According to a 1950 census, Nogales had a population of 6,153 with fewer than 100 African American families.[17] As such, the Grand Avenue/Frank Reed School often lacked students. A May 4, 1951, article in the Arizona Sun (an African American newapaper) claims that it had less than 25 students. For comparison, the Carver School, the segregated school in Yuma, had 152. [18] In his 1954 book Schools in Transition, American sociologist Robin Murphy Williams argues that “school segregation was the result of Anglo-American attitudes” and that discrimination in Nogales was “almost completely on the basis of color” where “persons of lighter complexion are assumed to be Spanish-American and are not discriminated against, whereas the darker individuals are usually refused service in places of public accommodation.”[19]

Due to the mandatory segregation of elementary schools in Arizona, young African American students had to walk past elementary schools that were closer to them on their way to the Grand Avenue/Frank Reed School. This had a profound effect on the students even after they graduated from the Grand Avenue/Frank Reed School. Administrator Doris Bynon McGuire said that “segregation in the elementary grades would suffice to set them apart when they reached High School.”[20]

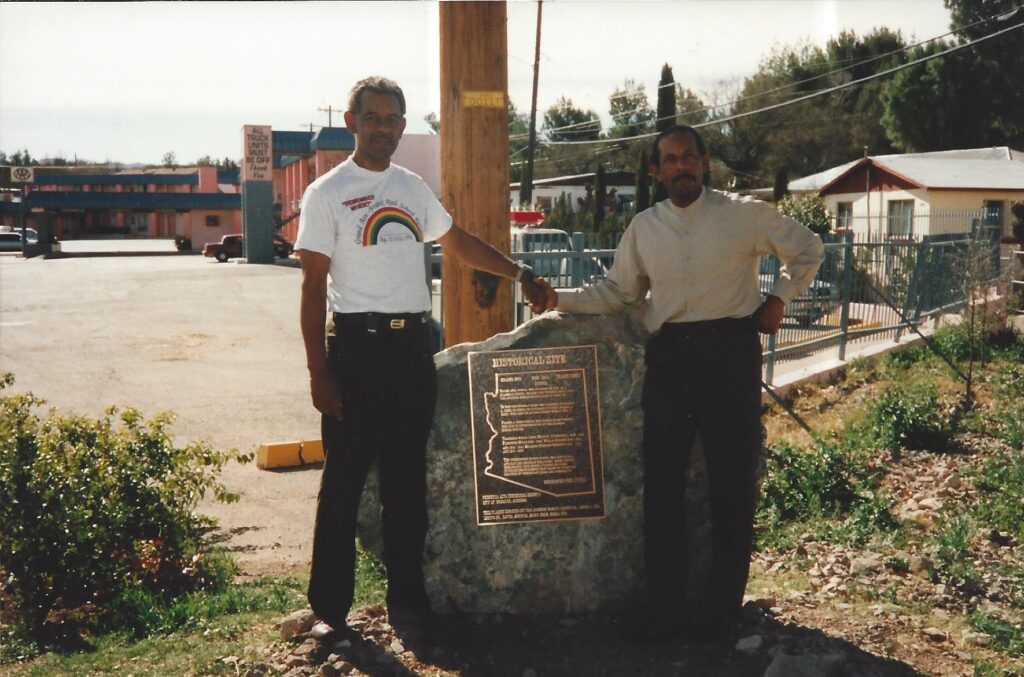

In 1951, the Arizona Legislature passed a law giving school boards the power to desegregate their elementary schools. One year later, in October of 1952, the Nogales Unified School District Board voted to desegregate its public schools. 16 students, 2 teachers and a janitor were integrated from the Frank Reed School into other Nogales elementary schools. [21] Unlike other desegregation efforts, which often met stiff pushback from parents and educators alike, the integration of Nogales public schools was relatively uneventful. As Williams put it, “in a community accustomed to differing ethnic groups, this change was not revolutionary.”[22] Today, all that remains of the Grand Avenue/Frank Reed School is a small historical marker.[23]

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas that the state segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th Amendment and, therefore, unconstitutional. The ruling was met with stiff resistance in the South. State and local governments passed laws to prevent the implementation of integration.[24] This pushback can largely be explained by the prevailing attitudes of America’s White population. According to a 1956 study conducted in Scientific American, only 48 percent of the White population approved of school integration. When narrowed to the White population living in the South, the number dropped to just 14 percent approval.[25] Functionally desegregating public schools would become one of the defining struggles of the American Civil Rights Movement.

Two former students from the Grand Avenue/Frank Reed School during the 1996 dedication of the site’s historical marker located at approximately 941 N. Grand Avenue in Nogales.

SOURCE: Historical Marker Database (https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=27113)

“The uniqueness of our school was due to our African and Mexican heritages. Even though segregated, this school turned out some outstanding students that grew up to be the leaders of yesterday, today and tomorrow.”

SOURCE: Historical Marker Database (https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=27113)

Conclusion

Our African American Heritage in Santa Cruz County

Miguel Grijalva (2024), Oil on Canvas

When Frank Reed left to go fight in World War II, he never could have imagined that the segregated school he was forced to attend as a child, as well as the access road to Nogales High School would be renamed in his honor. Reed’s story points to the arbitrary nature of segregation in Nogales. In 1916, Arizona Attorney General Wiley E. Jones wrote that Arizona’s segregation law “empowers trustees to segregate children of the African race, but does not empower the trustees to segregate children of the Mexican race unless, of course, children of the Mexican race might also be of African descent, by being intermingled with African blood through birth.”[26] That was the perception of Reed, a young Mexican boy with an African American father who was prejudiced against as such despite not being African American himself.

Charles Mingus returned to his birthplace at least once, when he crossed the border into Mexico to play shows in small restaurants. He remained fascinated with Latin music throughout his life, evidenced in his own compositions, such as “Ysabel’s Table Dance” on Tijuana Moods and the flamenco guitar on The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady.[27] He died in Cuernavaca, Mexico in 1979.

The legacies of segregation, of the intersection of the military and African American communities, and of the African American search for identity in Nogales are complicated and largely forgotten. However, these legacies played an important role in the development of Nogales during the 20th century.

Primary Documents

Document 1:

“Nogales Boy Killed in Action in New Guinea,” Nogales International, January 22, 1943.

Document 2:

“Nogales Ends Segregation,” Arizona Sun, October 17, 1952.

The Arizona Sun was a newspaper edited by and published for African Americans in Arizona which reported on issues and perspectives ignored by many mainstream newspapers.

About the Author

Kyle Kersey is currently an undergraduate history major at the University of Arizona. A native of Tucson, his writing has been published by the Daily Wildcat, Pima Post, and Under the Radar Magazine.

Bibliography

Arizona Council for Civic Unity. Close the Breach; [a Study of School Segregation in Arizona]. Phoenix, 1949.

Day, John Kyle. The Southern Manifesto: Massive Resistance and the Fight to Preserve Segregation. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014.

“Federal Officers Find Wood Alcohol in Border Liquor.” Arizona Republican, April 5, 1921.

Gabbard, Krin. Better Git It in Your Soul: An Interpretive Biography of Charles Mingus. Berkley, California: University of California Press, 2016.

Gay, Gerald M. “Nogales Fest Strengthens Charles Mingus Legacy.” Arizona Daily Star, April 17, 2014.

Giddens, Gary. Visions of Jazz: The First Century. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

“Grand Avenue School Named After War Hero.” Nogales International, March 26, 1943.

Hansen, Greg. “Veeck’s Influence is Still Felt.” Arizona Daily Star, February 26, 1998.

Hyman, Herbert H., and Paul B. Sheatsley. “Attitudes toward Desegregation.” Scientific American 195, no. 6 (1956): 35–39.

Lara, Genesis. “Bands Play in Mingus Jazz Festival.” Nogales International, April 22, 2024.

Mingus, Charles. Beneath the Underdog: His World as Composed by Mingus. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971.

“Nogales Boy Killed in Action in New Guinea.” Nogales International, January 22, 1943.

“Nogales Ends Segregation.” Arizona Sun, October 17, 1952.

Parra, Carlos Francisco. Americanization, Language Police, And the Promise of Education: Public School Formation and Educational Attainment in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Nogales, Arizona, 1880-1942. PhD diss., University of New Mexico, 2013.

Powers, Jeanne M. “Forgotten History: Mexican American School Segregation in Arizona from 1900–1951.” Equity & Excellence in Education 41, no. 4 (2008): 467–81.

“School Desegregation Week’s Leading Topic” Arizona Sun. May 4, 1951.

Ruelas, Richard. “How the Cactus League Came to Be in Arizona: A Search for Racial Tolerance.” AZ Central, January 18, 2019.

Williams, Robin M. Schools in Transition. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1954.

[1] Carlos Francisco Parra, Americanization, Language Police, And the Promise of Education: Public School Formation and Educational Attainment in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Nogales, Arizona, 1880-1942 (PhD diss., University of New Mexico, 2013), 43.

[2] “Nogales Boy Killed in Action in New Guinea,” Nogales International, January 22, 1943.

[3] “Nogales Boy Killed,” Nogales International.

[4] “Federal Officers Find Wood Alcohol in Border Liquor,” Arizona Republican, April 5, 1921.

[5] “Grand Avenue School Named After War Hero,” Nogales International, March 26, 1943.

[6] Krin Gabbard, Better Git It in Your Soul: An Interpretive Biography of Charles Mingus,(Berkley, California: University of California Press, 2016), 14-15.

[7] “Charles Mingus 1976.jpg,” Wikipedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Charles_Mingus_1976.jpg).

[8] Gary Giddens, Visions of Jazz: The First Century,(New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 455.

[9] Gabbard, “Better Git It in Your Soul,” 201.

[10] Gerald M. Gay, “Nogales Fest Strengthens Charles Mingus Legacy,” Arizona Daily Star, April 17, 2014.

[11] Genesis Lara, “Bands Play in Mingus Jazz Festival,” Nogales International, April 22, 2024.

[12] Richard Ruelas, “How the Cactus League Came to Be in Arizona: A Search for Racial Tolerance, AZ Central, January 18, 2019.

[13] Greg Hansen, “Veeck’s Influence is Still Felt,” Arizona Daily Star, February 26, 1998.

[14] Arizona Council for Civic Unity, Close the Breach; [a Study of School Segregation in Arizona], (Phoenix,1949).

[15] Arizona Council for Civic Unity, Close the Breach.

[16] Arizona Council for Civic Unity, Close the Breach.

[17] Robin M. Williams, Schools in Transition,(Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1954), 167.

[18] “School Desegregation Week’s Leading Topic,” Arizona Sun, May 4, 1951, 8.

[19] Williams, Schools in Transition, 167-168.

[20] Parra, Public School Formation, 42-3.

[21] “Nogales Ends Segregation,” Arizona Sun, October 17, 1952; Williams, Schools in Transition, 168.

[22] Williams, Schools in Transition, 169.

[23] Parra, Public School Formation, 44.

[24] John Kyle Day, The Southern Manifesto: Massive Resistance and the Fight to Preserve Segregation (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014), 7-12.

[25] Herbert H. Hyman and Paul B. Sheatsley, “Attitudes toward Desegregation,” Scientific American 195, no. 6 (1956): 36.

[26] Jeanne M. Powers, “Forgotten History: Mexican American School Segregation in Arizona from 1900–1951,” Equity & Excellence in Education 41, no. 4 (2008): 470.

[27] Gabbard, “Better Git It in Your Soul,” 118.