Muralism as the Affirmation of Mexican American and Latino Community

Ismael F. Illescas, Ph.D.

Key Concepts

- Mexican muralism, especially the public art of Los Tres Grandes, inspired and influenced Mexican American and Latino muralism to depict their community’s history, culture, and traditions in the United States.

- Chicano muralism was a way to give voice to Mexican American communities artistically and publicly across the Southwest of the United States.

- The Great Wall of Los Angeles is an example of how Chicano muralists, with the help and collaboration of local youths, residents, community members, and families, can make alternative histories publicly accessible through art.

- The murals in Nogales, Arizona, exemplify how the tradition of Mexican, Chicana/o, Mexican American, and Latino muralism still speaks for today’s Mexican American and Latino communities, cultures, and histories in public display.

Key Terms

- Los Tres Grandes — the three great Mexican mural artists, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco.

- Aesthetics — relating to the beauty and taste in art.

- Muralists — people who paint large-scale artworks in public spaces.

- Chicana/o — Mexican Americans in the United States chose this name as a badge of honor and pride in their communities.

- The Chicano Movement — also known as El Movimiento or the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, was when Mexican American communities across the United States fought for their civil rights.

- Chicana/o Muralism — Mexican American public art that depicts a collective identity, empowerment, culture, and history.

- The Great Wall of Los Angeles — one of the largest public artworks in the world located in Los Angeles that depicts Mexican Americans and various ethnic and racial groups’ contributions to the city, the United States, and the world.

What is the Relevance of Nogales Borderland Muralism?

Muralism as the Affirmation of Mexican American and Latino Community

Ismael F. Illescas, Ph.D.

Introduction

A girl rides a hummingbird holding U.S. and Mexican flags. A bright walnut shaped like a heart. A pair of hands holds produce grown in Mexico. A Virgen de Guadalupe with the colors of the U.S. and Mexican flags on her veil. These images adorn the walls of Nogales — and you can see each one, too! These murals across the border town of Nogales are examples of public art representing the culture, pride, and hopes of people living on the frontera.

Figure 1: “Binational Hummingbird”paintedby Karla Osete at 981 N. Grand Ave, Nogales, Arizona.[1]

Muralism was popularized by a famous group of Mexican artists known as Los Tres Grandes. Los Tres inspired Mexican American and Latino artists in Los Angeles, Nogales, and other cities and towns in the United States. For Mexican, Mexican American, and Latino communities, muralism is large public art depicting and honoring a collective identity, culture, and history. This artistic tradition helped define Mexican identity in the 20th century and has inspired many Mexican Americans and Latinos in the United States. As we will see, the murals throughout Nogales and Santa Cruz County is part of a long Mexican and Mexican American tradition of muralism and public art that gives voice to a community’s history, culture, and aspirations.

Los Tres Grandes

Los Tres Grandes – Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Jose Clemente Orozco – covered walls of buildings with large public art depicting Mexican history to educate ordinary Mexican people — most of whom couldn’t read or write. Their major artworks blasted on large-scale walls depicting Mexican identity, history, and culture came to have a big impact not just in Mexico but worldwide.

Figure 2: “From the Conquest to 1930” mural painted by Diego Rivera at the National Palace, Mexico City.

Los Tres created art funded by the post-revolutionary government of Mexico in the 1920s as part of producing a national Mexican identity. Their focus was on ordinary Mexicans, who they believed had the potential to shape the nation’s future. Their main goals included creating a vibrant national identity, depicting forgotten histories, and bringing art out of the museums to the public. Their murals, like Diego Rivera’s “From the Conquest to 1930” in the national palace, drew inspiration from Mexican history and depicted Aztec warriors fighting Spanish colonizers, peasants fighting for their land in the Mexican Revolution, and ordinary workers fighting for living wages and better living conditions in Mexico City. [2]

Los Tres Grandes’s art highlighted Mexican history and created new narratives and aesthetics — the appreciation of beauty and artistic taste. The aesthetics of their works emphasized making large and beautifully painted murals publicly accessible to reflect, empower, and inform communities.

Figure 3: Carlos Ibarra’s “Nogales” mural painted in Morley Avenue above La Cinderella storefront. Notice how the nogal/walnut is the heart at the center of Ambos Nogales.[3]

The aesthetic choices and mural tradition of Los Tres are present today in murals like “Nogales,” painted by Carlos Ibarra in 2024, which depicts a bright black walnut tree in the middle — a nogal! — to symbolize the U.S.-Mexican border, the heart of Ambos Nogales, while depicting landmarks from both cities.

Los Tres public-facing aesthetic choices inspired many Mexican American and Latino muralists across the Southwest of the United States, from the artistic renewal of the 1960s to today, as we will see in the next sections and evidenced in the works of Carlos Ibarra and many muralists in Nogales.

The Chicano Movement and Chicano Muralism

The Chicano Movement was an important moment in Mexican American history that began in the 1960s. Many Mexican American youths called themselves Chicana/o — transforming an initially insulting word into an expression of a new and empowered identity.

The Chicano Movement fought for respect and dignity for Mexican Americans throughout the U.S. Southwest. Within the Movement, Chicanas/os affirmed their history, cultures, traditions, languages, and contributions to this country. They fought for better working and living conditions and demanded the desegregation of schools in cities like Tucson and Los Angeles. To be a Chicana/o meant to fight for respect, civil rights, and community betterment.[4] Chicana/o muralism was an essential part of this process.

Chicana/o muralism — large-scale public artworks by Chicanas/os to empower their communities — spread the movement’s ideas of community empowerment to a broader public. Much like Mexican muralism was vital to reinscribing Mexican history and identity in Mexico, Chicana/o muralism worked to empower Mexican Americans in the United States. Large and beautiful murals became a way to inform and educate communities and affirm a social presence.

Early Chicana/o muralists painted Indigenous histories through depictions of Mayan and Aztec culture, Mesoamerican pyramids, religious figures like the Virgin de Guadalupe, revolutionary Mexican figures like Emiliano Zapata and Francisco “Pancho” Villa, and Mexican American civil rights leaders like Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, who co-founded the United Farm Workers Association.

Chicano muralists did this to raise Mexican Americans’ and other Latinos’ pride and self-respect. The famous East Los Angeles mural We Are Not a Minority” (1978) is a great example of how artists used muralism in public space to promote community pride, self-awareness, and empowerment. “We Are Not a Minority,” which features the Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara, is meant to remind Latinos that they have a deep history and culture in the United States, even if its not always taught in school or acknowledged by our elected leaders.

Figure 4: “We Are Not a Minority” mural painted at the Estrada Courts in East Los Angeles.

Chicana/o muralists conversed with community members about their culture, living conditions, and local issues to develop a mural concept. Working with local artists and residents ensured the community had a voice in what was painted in their neighborhoods.

The cultural pride murals like “We Are Not a Minority” promoted began appearing in Nogales during the 1990s as the Chicano muralism movement expanded from California throughout the Southwest, including El Paso and Tucson. Despite being a smaller city, Nogales’s murals have often encouraged local people to better value themselves and their binational, bicultural identities.

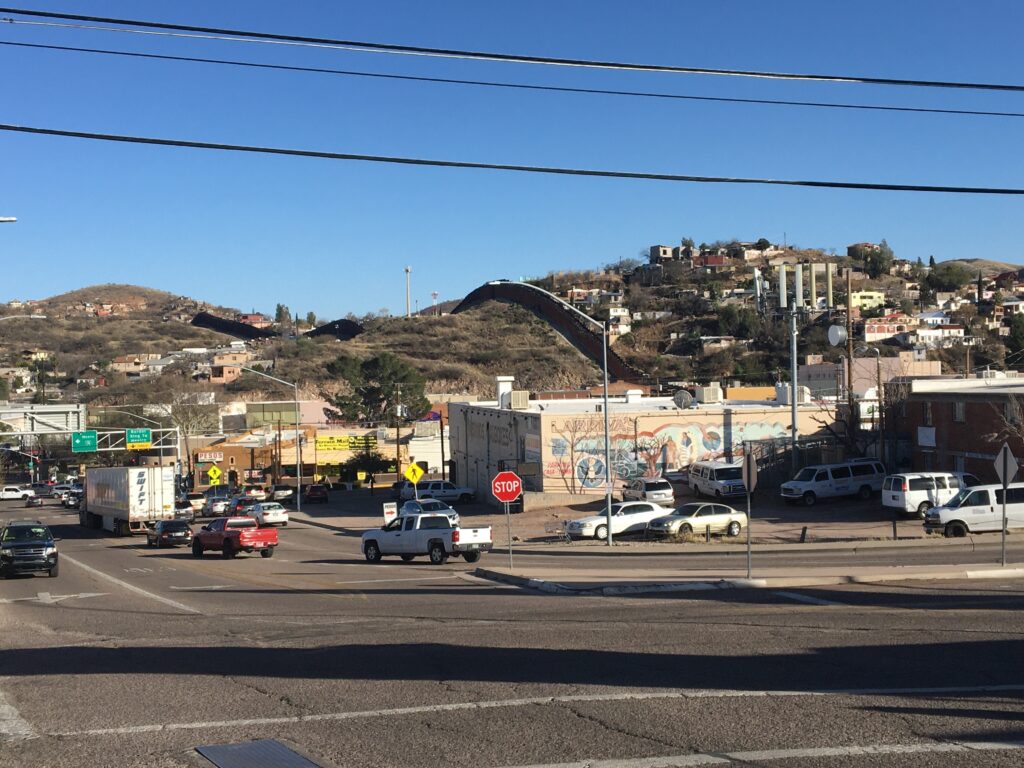

Following the uplifting spirit of the Mexican and Chicana/o muralist tradition, Nogales High School art teacher Martin Moreno painted “Reflecciones de la Juventud” (1995) near the Grand Avenue Port of Entry. The mural honors Indigenous nations, Mexican religious figures like the Virgen de Guadalupe, and the mix of national identities of people living in Nogales by dressing the Virgen with U.S. and Mexican flags.

Figure 5: “Reflecciones de la Juventud” is painted at the end of Interstate 19, two blocks from the main border crossing between Nogales, Arizona, and Heroica, Nogales, Sonora, Mexico.[5]

The binational U.S.-Mexican flags mantle the Virgen de Guadalupe is depicted as wearing is meant to encourage people in Nogales, Santa Cruz County, and the rest of the border area to be proud of themselves and their culture.

With funding from the Santa Cruz County Superintendent’s Office, Martin Moreno painted this mural with the help of NHS students. Until the 2010s, “Reflecciones de la Juventud” was the largest mural in Nogales, Arizona.

The Great Seal of the United States of America.

Judith Baca and “Mi Abuelita”

Most Chicana/o muralists relied on community. They worked in neighborhoods with self-taught artists, residents, and young people, teaching them techniques to join the larger mural movement. Their murals painted stories untaught in textbooks that highlight Mexican American and Latino history, identity, and culture. Some prominent figures within the Chicana/o Movement are muralists like Judith Baca.

Judith Baca is an important figure in the Chicana/o muralist movement. She is a Chicana artist, activist, and professor of Chicano Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. Baca, a first-generation college graduate, earned a master’s degree in fine arts and wanted to make art accessible to people outside art galleries and museums.

After completing art school, she studied muralism at Taller Siqueiros in Cuernavaca, Mexico, where she became inspired by Mexican muralists. Returning to Los Angeles, Baca collaborated with community members to paint large murals in L.A.’s Mexican American neighborhoods. One of her earliest murals is “Mi Abuelita” (My Grandmother) in 1970. This mural was huge! It covered the three-wall outdoor stage in Hollenbeck Park in East Los Angeles. It depicts a Mexican American grandmother with her arms outstretched, giving a hug to recognize the important position of women — especially abuelitas — in Mexican and Mexican American families.

Figure 6: “Mi Abuelita” mural, painted in 1970 at Hollenbeck Park in Los Angeles, CA.[6]

What was most important about “Mi Abuelita” was how youths, residents, and rival gang members came together and used public art to create peace and unity. Listening to and working with residents to plan what they want to see in their neighborhoods became an important element of Chicana/o muralism. Unfortunately, “Mi Abuelita” was painted over, which shows that murals can easily be destroyed.

The Great Wall of Los Angeles

Figure 7: “The Great Wall of Los Angeles” at the Tujunga concrete arroyo in north Los Angeles. [10]

Judith Baca and her students also created one of the world’s largest murals – The Great Wall of Los Angeles! Located in the Tujunga Wash Flood Channel in northern Los Angeles, it was executed by Judith Baca and over 400 local youths, residents, and families. Stretching a half mile along the Tujunga concrete arroyo, the mural tells the epic story of the histories and contributions of the city’s ethnic groups from prehistoric times to the 1950s to the present, with stories continuing to be painted today!

In 2021, Baca stated about the mural, “The story I wanted to tell was the story of the history that wasn’t recorded in the history books, the history of people of color, the history of women, of Indigenous people, to look at what was missing from the story of America, and to reconstruct that and teach it to the young people, who’d begin to learn about each other.”[8] The “Great Wall of Los Angeles” is not just a beautiful work of public art. Baca says it “reappear[s] the disappeared stories of ethnic populations… that built our city, state, and nation.”[9]

The Great Wall of Los Angeles is an example of the influence of both Mexican and Chicana/o muralism across the United States. As we will see, the murals across Nogales, Arizona, continue this tradition of public art.

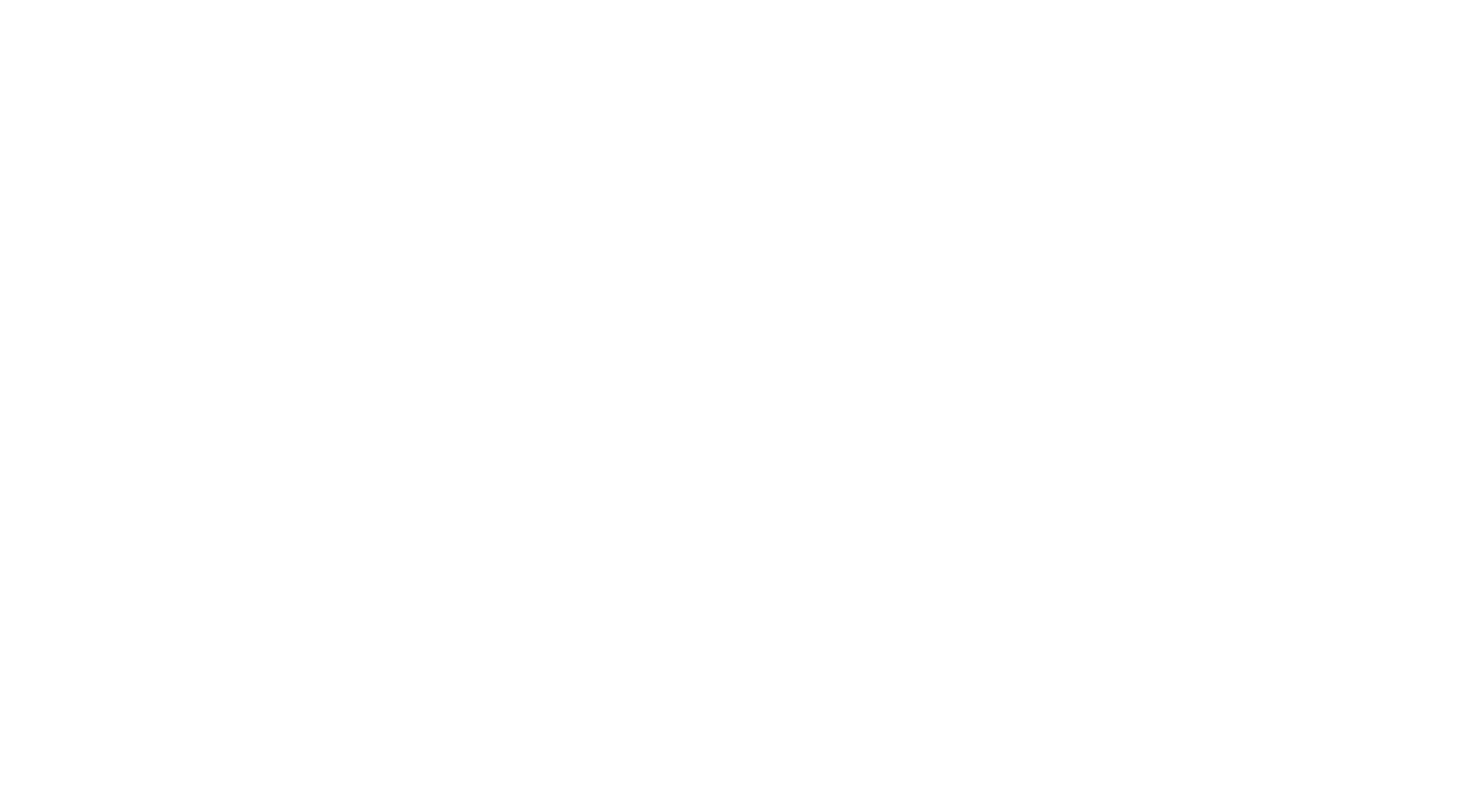

Nogales Borderland Muralism

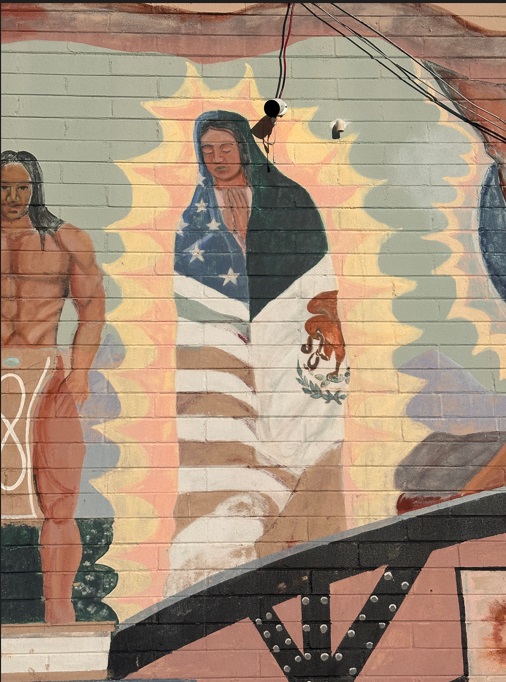

Figure 8: “Binational Handshake,” painted one block from the U.S.-Mexican border, depicts Nogales as a meeting place between Mexico and the United States.[11]

The rich tradition of Mexican and Chicana/o muralism continues at the borderlands of Nogales and Santa Cruz County. For example, Isis Casorla and Alan Gonzalez’s “Binational Handshake” (2005), painted a block from the U.S.-Mexican border, illustrates the local pride of Ambos Nogales. It highlights Nogales as a unique place where the people, cultures, and traditions of the United States and Mexico meet. Binational respect, cooperation, and unity between people from the United States and Mexico are indicated by the two hands, each adorned with their respective flags, meeting and greeting each other at the frontera.

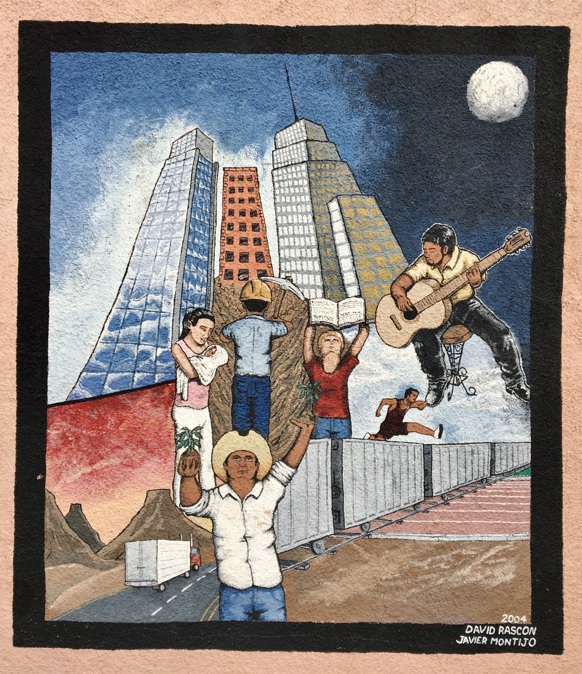

Figure 9: “Latinos on the Move” by David Rascon and Javier Montijo.[12]

Similarly, the mural “Latinos on the Move” (2004) by David Rascon and Javier Montijo depicts Mexican American and Latino empowerment, success, and belonging in Nogales. The mural honors the contributions of Latino families, workers, students, artists, musicians, and athletes. It depicts a student with a book, a worker with a hard hat building the city, a mother with her baby, a man playing the guitar, and an athlete jumping over the train (representing the border), signaling the importance of education and family, of overcoming challenges and borders, and of the contributions of Mexican Americans and Latinos.

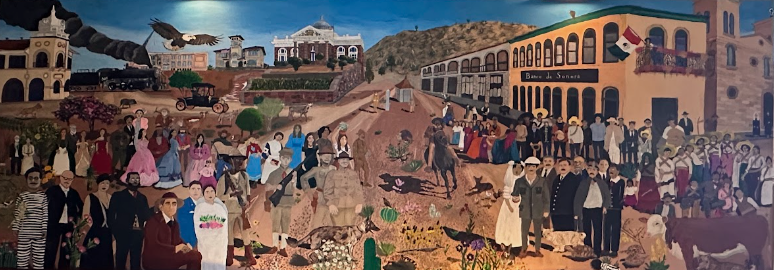

Finally, the massive mural “Nogales” (2024) by Carlos Ibarra stretches 18 feet high and 36 feet long, highlighting the binational life and landscape of Ambos Nogales. Ibarra’s “Nogales” is located one block away from the Morley Avenue/Calle Elías Port of Entry in the historic heart of Ambos Nogales.

Continuing the Mexican and Chicana/o muralist tradition, Ibarra’s large-scale mural emphasizes the connections between the people, communities, landscapes, and historical sites of the sister cities of Nogales.

“Nogales” depicts images of the communities of the sister cities, like the historic 1904 Courthouse in Nogales, Arizona, the church tower of the Parroquia De La Purísima Concepcíon in Nogales, Sonora, and the white archway of the DeConcini Port of Entry — all familiar to the communities living in the borderlands. A walnut tree growing on the U.S.-Mexican border with a heart in the middle symbolizes our community’s transnational character and how our family, social, and economic ties go beyond borders.

Figure 10: “Nogales” mural painted above La Cinderella storefront. It depicts the sister cities of Nogales.[13]

Conclusion

The murals throughout Nogales and Santa Cruz County are part of a long Mexican, Chicana/o, and Mexican American muralism that gives voice to a community’s history, culture, and aspirations. From Los Tres Grandes, who began an artistic tradition of public art to teach and empower ordinary Mexicans, to Chicana/o muralists like Judith Baca, whose large murals represented people left out of textbooks, to the murals that adorn Nogales today, these traditions and legacies carry on!

Muralists in Nogales continue to paint murals that reflect, represent, and uplift its communities. The next time you walk and see a mural in Nogales – such as An October (1915) Day in Ambos Nogales (at the Historic 1904 Courthouse) and The Present Meets the Past (at the Nogales Public Library) – appreciate it and recognize it as a part of a long Mexican and Chicana/o muralist tradition that is alive within our time.

Author Bio

Ismael F. Illescas is an Ecuadorian migrant who grew up in Los Angeles, California. He studies, researches, and writes about public art. He is an Assistant Professor in the Ethnic Studies Program at Chabot College in Hayward, California.

Bibliography

Baca, Judith. Mi Abuelita.1970. photograph. Judy Baca website. https://www.judybaca.com/art/miabuelita1970/.

Baca, Judith. The Great Wall of Los Angeles, 1978, photograph, Judy Baca website. https://www.judybaca.com/art/great-wall-of-los-angeles-1974-present/

Baca, Judith, “Whose Monument? Where? Public Art in a Many-Culture Society.” In Chicano and Chicana Art: A Critical Anthology, edited by Jennifer A. González and C. Ondine Chavoya, 304–9. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2019.

Brown, Jeffrey, and Lena I Jackson. “How Judy Baca’s Murals Help Recover History through ‘Public Memory.’” UCLA School of the Arts and Architecture, November 30, 2021.

Casorla, Isis and Alan Gonzalez. Binational Handshake. 2005. Original photograph. Carlos Parra.

El Congresso de Artistas Cósmicos de Las Américas de San Diego. We Are Not a Minority. 1978. Photograph. Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles. https://www.themcla.org/murals/we-are-not-minority

Flattley, Megan. “The History of Mexico: Diego Rivera’s Murals at the National Palace.” Smarthistory: The Center for Public Art History, September 22, 2020. https://smarthistory.org/mexico-diego-rivera-murals-national-palace/

Ibarra, Carlos. Nogales. 2024. Original photograph. Carlos Parra.

Moreno, Martin. Recuerdos de la Juventud, 1995, Original photograph. Carlos Parra.

Muñoz, Carlos. “The Chicano Movement – Mexican American History and the Struggle for Equality.” Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung New York Office, April 2013. https://rosalux.nyc/wpcontent/uploads/2021/09/munoz_the_chicano_movement.pdf

Rascon, David and Javier Montijo. Latinos on the Move. 2004. Original photograph. Carlos Parra.

[1] Karla Osete, Binational Hummingbird, 2019, original photograph, Carlos Parra.

[2] Megan Flattley, “The History of Mexico: Diego Rivera’s Murals at the National Palace,” Smarthistory: The Center for Public Art History, September 22, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/mexico-diego-rivera-murals-national-palace/.

[3] Carlos Ibarra, Nogales, 2024, original photograph, Carlos Parra.

[4] Carlos Muñoz, “The Chicano Movement – Mexican American History and the Struggle for Equality,” Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung New York Office, April 2013, https://rosalux.nyc/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/munoz_the_chicano_movement.pdf.

[5] Martin Moreno, Recuerdos de la Juventud, 1995, original photograph, Carlos Parra.

[6] Judith Baca, Mi Abuelita.,1970, photograph, Judy Baca website, https://www.judybaca.com/art/miabuelita1970/.

[7] El Congresso de Artistas Cósmicos de Las Américas de San Diego, We Are Not a Minority, 1978, photograph, Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles, https://www.themcla.org/murals/we-are-not-minority

[8] Jeffrey Brown and Lena I Jackson. “How Judy Baca’s Murals Help Recover History through ‘Public Memory.’” UCLA School of the Arts and Architecture, November 30, 2021. https://arts.ucla.edu/single/how-judy-bacas-murals-help-recover-history-through-public-memory/#!

[9]Judith Baca, “Whose Monument Where? Public Art in a Many-Culture Society,” in Chicano and Chicana Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Jennifer A. González and C. Ondine Chavoya (North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2019), 305.

[10] Judith Baca, The Great Wall of Los Angeles, 1978, photograph, Judy Baca website, https://www.judybaca.com/art/great-wall-of-los-angeles-1974-present/

[11] Isis Casorla and Alan Gonzalez, Binational Handshake, 2005, original photograph, Carlos Parra.

[12] David Rascon and Javier Montijo, Latinos on the Move, 2004, original photograph, Carlos Parra.

[13] Carlos Ibarra, Nogales, 2024, original photograph, Carlos Parra.