John P. Langellier, Ph.D.

Introduction

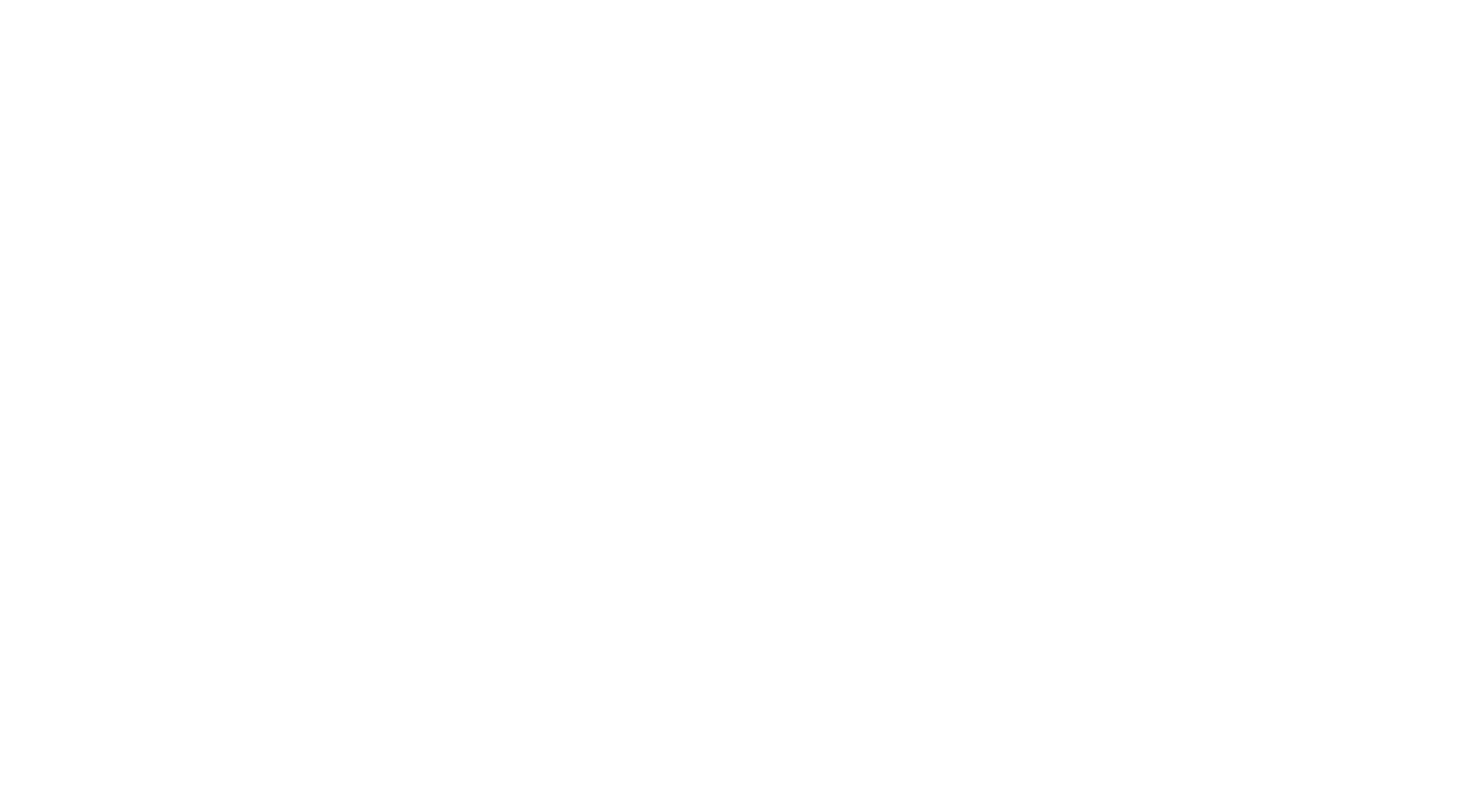

Henry Ossian Flipper was a model for those who display the strength and determination to overcome major trials and great difficulties. In spite of many disadvantages from little money and few opportunities as he grew up in a small rural community to racism throughout his life, he persevered. In southern Arizona, he especially showed his resolve along with his many wide ranging and incredible abilities. From the 1880s-1890s, Flipper lived in Nogales, Arizona as well as resided in other places within the territory. While here, he drew on his education to succeed in many challenging occupations and diverse undertakings. This included the protection of the town’s legal rights from land speculators. He also briefly served as editor of the Nogales Sunday Herald, the town’s only newspaper at that time.

Early Years of Adversity

Born on March 21, 1856, to enslaved parents in Thomasville, Georgia, remarkably Henry Ossian Flipper conquered the considerable disadvantages of his youth. Both intelligent and ambitious, he gained a hard-to-obtain appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Once there, Flipper endured powerful discouraging obstacles. During his time as a cadet, he bore personnel insults from white classmates, all of whom shunned him. For four lonely years, few of them ever spoke to him except when military requirements dictated.

Even so, he never gave up his dream. In 1877, he became the first African American graduate of the United States Military Academy. This was no easy accomplishment. Flipper shared these trying days in his autobiography, The Colored Cadet at West Point, an extraordinary account that demonstrated his skills at expression even at an early age.

After Flipper graduated, he received his commission as a second lieutenant in the segregated Tenth U.S. Cavalry, one of the “Buffalo Soldier” regiments where all the enlisted men were Blacks and all the other officers were Whites. After four years with Company A, Tenth Cavalry, he faced charges for disobeying army regulations. The court-martial that followed found him guilty of “conduct unbecoming an officer.” This verdict resulted in Flipper’s dismissal from the military. For much of the remainder of his life, he unsuccessfully attempted to overturn the ruling, which he claimed had been motived by prejudice.

Flipper Reinvents Himself on the Border and Defends Nogales from Land Speculators

Following his dismissal from the Army, Flipper became a civilian. He now had to earn a living outside the military. However, as historian Theodore Harris has stated, Flipper “won professional respect along the border” for his several civilian jobs. Specifically, Flipper worked as an engineer on behalf of mining companies in the U.S. Southwest and northern Mexico. Flipper became fluent in Spanish as his work creating survey maps and other reports for the mining companies required him to read and translate Spanish and Mexican legal documents. It was during this point in his life that this capable individual arrived in Nogales. Many newspapers reported favorably in their accounts of him such as Tucson’s Arizona Weekly Citizen on February 15, 1890. The article indicated Flipper “came to Nogales five years ago, since which he has been constantly employed as a civil engineer by large corporations. He is a hard worker, and deserves his success.” A few years later, on January 21, 1893, the same newspaper added: “The lieutenant’s laugh once heard is never to be forgotten.”

Previously, the April 15, 1899 edition of Nogales’ Border Vidette observed that Flipper became “one of the best authorities on land and mining laws of the United States and Mexico.” In fact, as Jane Eppinga, one of Flipper’s biographers declared, he gained a fine reputation “as an engineer, Spanish translator, Justice Department special agent, author, historian, and newspaper editor.”

Because of his personality and work ethic Flipper frequently enjoyed fair treatment in Arizona. As Florence’s Arizona Weekly Enterprise remarked on September 7, 1889, “Lieutenant H.O. Flipper of Nogales, came in Monday morning and was greeting friends at the feast last night.” Also, when away from his home in Nogales, Arizona, during his travels in the borderlands he evidently lodged in local accommodations without being refused a room, which usually was the case during the discriminatory era. Nevertheless, he often endured the widespread prejudice of his times.

Regardless of bias, Flipper successfully invested in real estate. At first, he obtained a lot in Nogales, Arizona. Later, he bought another property on what became Nelson Street. Further, Flipper even served for a short time as a deputy post master, plus took part in local politics and temporarily stood in for a Nogales newspaper editor. Although he only edited the Nogales Sunday Herald for a few months in 1895, Flipper became the first Black editor of a White-owned newspaper in Arizona and possibly the United States.[1] What is more, he gathered and sometimes shared intelligence about the activities in Mexico during the turbulent revolutionary events south of the border. Flipper often traveled to Washington, D.C. to share his findings to important U.S. government officials.

Likewise, Flipper’s many journeys brought him to far more remote places than Washington. As Prescott’s Arizona Weekly Journal-Miner mentioned on July 31, 1889, while accompanying a surveying party in a remote region “the camp their cook managed to get a centipede four inches long in the coffee-pot.” The group did not discover the additional ingredient “until breakfast was over and the grounds were being emptied out. Some of the party made desperate efforts to get sick…, but nobody died.” Because Flipper drank “neither tea nor coffee, and who fell ‘dead safe,’ says it was refreshing to note the sudden and enthusiastic manner in which the Mexican laborers in the party resorted to their wonted religious incantations when they found that they had been drinking centipede soup.”

Over three years earlier, the Arizona Weekly Citizen ran a story on June 12, 1886 that depicted another side of Flipper’s personality. The article read: “A Mexican in the employ of the Sonora Land Company, on the departure of the surveying outfit Monday last, being furnished with a horse, rifle and ammunition, considered this, as he expressed himself, to be a good chance to visit his family in Arizona. He deserted the party with his outfit, but was overhauled by Lieutenant Flipper, who promptly turned him over to the civil authorities….”

In 1891 the Town of Nogales employed Flipper to defend it from land speculators who argued the town was built on a single property belonging to a single family. This dispute, known as Nogales de Elias land grant case (1893), went all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court. He served as the government’s only witness, and his testimony resulted in the grant’s being declared invalid. The ruling saved the property of hundreds of landowners in Nogales who were at risk of being kicked out or taken advantage of by the land speculators in the Nogales de Elias case. Flipper’s activity in the community led to his appointment as a special agent for the United States Court of Private Land Claims in reviewing property issues raised by land grant claims in Southern Arizona.

In gratitude for Flipper’s helping to win this significant court case, a number of people from Nogales honored him with a banquet. As further recognition, the U.S. Attorney who hired Flipper revealed the formidable barriers the former cavalry officer had to be overcome. In a telling summation, the attorney recognized Flipper’s “talents, attainments and education” which stood out despite racial discrimination. The lawyer acknowledged that the prejudicial hurdles Flipper faced forced him “to seek his books for companionship and recreation” but these pursuits allowed him to “obtain the respect of scholars and men of learning who know him….” In so doing, he “made for himself a name and a credit, as a private citizen and a government official, of which any man might well be proud.”

In some ways, Flipper notable attainments could be traced to one particular strength. As he wrote of himself: “I am as stubborn as a mule and never so happy as when someone has the temerity to oppose me.”

Legacies: Flipper and Rescuing Arizona’s African American Heritage

During his lifetime, this “remarkable character” as respected historian J. Frank Dobie referred to him, was among the first African Americans to be acknowledged for his work as a civil engineer. In fact, Flipper joined the Association of Arizona Civil Engineers, and became a member of the prestigious National Geographic Society, as well as the Southwest Society of the Archaeological Institute of America.

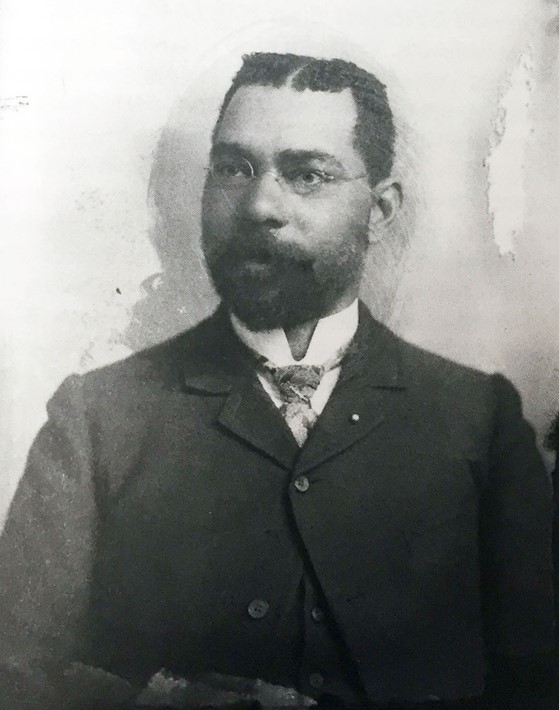

Just as fascinating, though, is the role Flipper played in saving the U.S. Southwest’s African American Heritage. Because of the background research his engineering work required, Flipper began writing historical articles and booklets of his own. One of his most significant – and which was lost for decades – was his 1896 booklet Did a Negro Discover Arizona and New Mexico? Written in Nogales and published from the Herald’s printing room, Flipper proclaimed the importance of African Americans in what became the United States by discussing the life of Estevanico (or Esteban de Dorantes), who “was the first foreigner to tread upon what are now the Territories of Arizona and New Mexico.”

Estevanico was an enslaved Black Moroccan who accompanied the Spaniards in their early explorations of North America. Surviving shipwrecks in Florida and Texas in 1528, Estevanico and three other men (including Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca) walked thousands of miles through swamps, deserts, and countless indigenous groups in an 8-year journey to Mexico City through what is now Texas, Chihuahua, Sonora, and Sinaloa. Estevanico’s observations and strength made him valuable for the Spanish Empire as it searched for cities of gold in what is now Arizona and New Mexico. The Arab and Spanish-speaking Estevanico went ahead of the 1539 Fray Marcos de Niza expedition as a scout accompanied by indigenous interpreters. Estevanico therefore became the first non-indigenous person to enter Arizona, likely in or near Santa Cruz County, in 1539. Because of this, Flipper concluded that to Estevanico “belongs the honor of having discovered” the Southwest. Estevanico had been long forgotten in favor of de Niza – Flipper’s booklet helped begin rescuing Estevanico’s story and the African American legacy in Arizona.

Regrettably, celebration of Flipper’s attainments was not widespread during his lifetime. In fact, deserved recognition began very slowly after Flipper’s death from a heart attack, on May 3, 1940, at his family’s home in Atlanta, Georgia. Three and a half decades after his passing, West Point at last honored Flipper with a bronze statue in recognition that he was first Black cadet to graduate from the Academy. President Bill Clinton officially pardoned Flipper on February 19, 1999. Each year a West Point graduate who best displays “the highest qualities of leadership, self-discipline, and perseverance in the face of unusual difficulties while a cadet” receives the Henry O. Flipper Award. These acknowledgements and several biographies, books and articles now exist that credit him for his many contributions.

SOURCE: Waymarking.com (https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WMGQYM_2nd_Lt_Henry_Ossian_Flipper_Fort_Leavenworth_KS)

Flipper’s accomplishments are mostly unknown in Nogales and in Santa Cruz County, despite his remarkable achievements. Perhaps this will change someday as Nogales/Santa Cruz County residents rediscover their history?

Suggested Reading:

For more on Flipper’s Nogales, U.S.-Mexican borderlands adventures (and to read it in his own words!) check out:

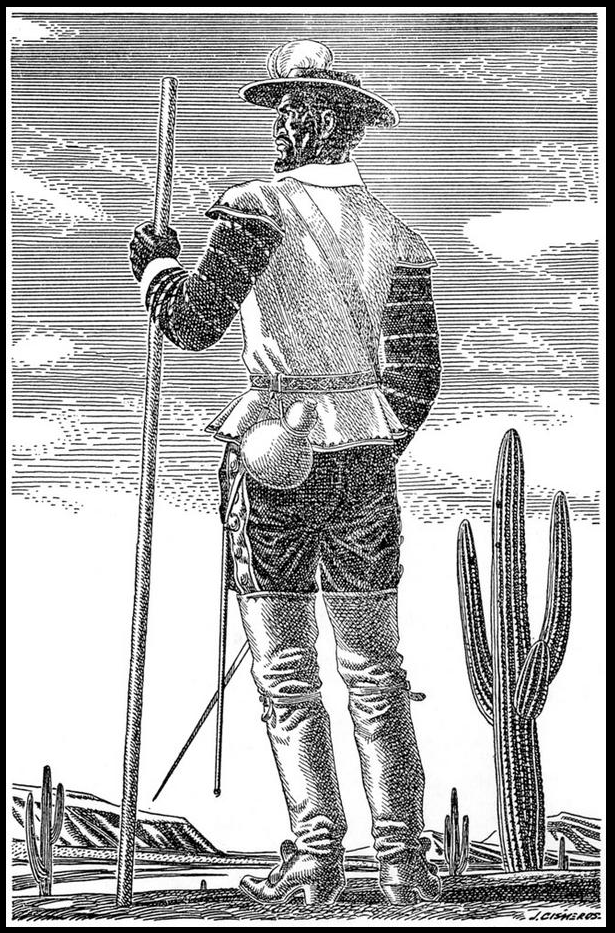

Black Frontiersman: The Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper, First Black Graduate of West Point (1997), edited by Theodore D. Harris

Bibliography

Arizona Weekly Citizen (Tucson, AZ).

Arizona Weekly Enterprise (Florence, AZ)

Arizona Weekly Journal-Miner (Prescott, AZ)

Border Vidette (Nogales, AZ).

Dobie, J. Frank. Apache Gold and Yaqui Silver. Boston, 1950.

Eppinga, Jane. Henry Ossian Flipper: West Points’ First Black Graduate. Fort Worth, TX: Wild Horse Press, 2015.

Flipper, Henry O. Black Frontiersman: The Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper, First Black Graduate of West Point, compiled and edited with introduction and notes by Theodore D. Harris. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1997.

_____. The Colored Cadet at West Point: Autobiography of Henry Ossian Flipper, U.S.A. First Graduate of Color from the U.S. Military Academy. New York: Homer Lee & Co., 1878.

_____. Did A Negro Discover Arizona? Nogales, AZ, c.1896.

Johnson, Barry C. Flipper’s Dismissal: The Ruin of Lt. Henry O. Flipper, U.S.A. First Coloured Cadet of West Point. London: Privately Printed, c. 1980.

Robinson, Charles M. III, The Court Martial of Lieutenant Henry Flipper. El Paso: University of Texas at El Paso, 1994.

tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/flipper-henry-ossian.

[1] Theodore Harris, Black Frontiersman: The Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University, 1997), 7-9.